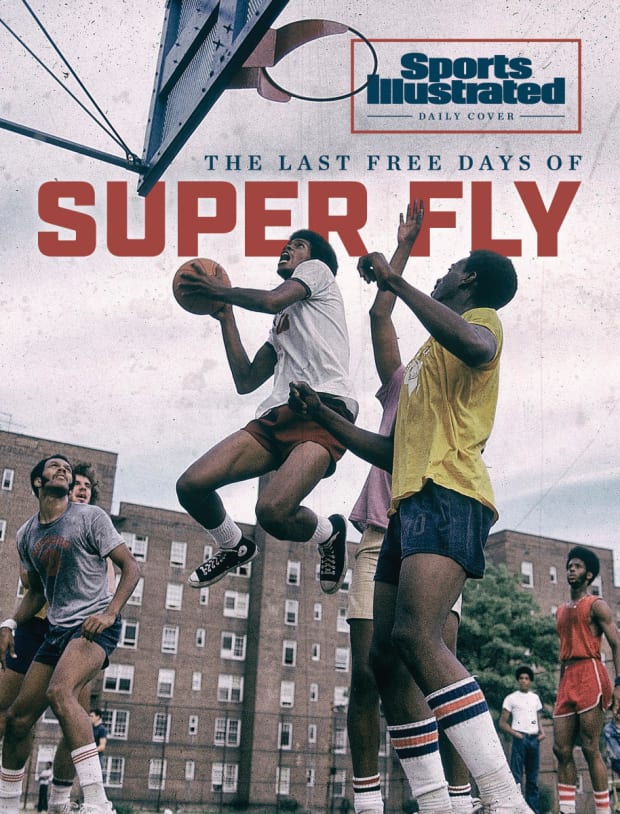

He was a hero of hot New York summer nights. A blacktop virtuoso. An untamable talent. A reclamation project. Now that he’s in prison, though, busted for running a heroin ring, his whole story needs retelling.

James Williams was a watched man when he strode with his arrogant gait into the Brownsville Recreation Center on the afternoon of July 14, 2016.

He wore eyeglasses with red lenses, two diamonds in his left ear and a gold chain around his neck as he arrived to oversee a youth basketball game in his old Brooklyn neighborhood. Stopping in the gym’s doorway, he noted that afternoon how players often goaded him, even at 63, to get back on the court. Fly—a nickname he gained either for his attire or his moves; depends who you ask—was revered around these parts for his fleeting 1970s heyday with the Spirits of St. Louis of the old ABA, and before that at Austin Peay, where as a freshman he led the Governors to their only Sweet 16 appearance. And while old-age Fly welcomed a shooting challenge here or there, he preferred to watch from the sideline. He monitored the kids league at the rec center and checked in at the main office, with his name below an AUTHORIZED PERSONNEL placard, not far down the hall from a mural someone had years ago painted of him on a gymnasium wall. “I love it,” Williams said, weighing it all. “You supposed to be happy at this age.”

Here he allowed himself a few slow, halting laughs, as if cognizant of the pacemaker doctors had implanted in 2011, after decades of destructive drug use and street violence had written a long, dark postscript to his short, flashy professional career. He’d lost parts of his lungs and his kidneys from a shotgun blast to the back in a robbery gone bad. He had a bullet lodged in the left side of his jaw; he pointed to another entry wound in his left leg and one more near his right knee. He noted the three screws in his hip and recounted going into cardiac arrest. “I’ve been through hell,” he said. “But I’m back, baby!”

After negotiating his way through an era of recidivism and relapses, Williams had found a second life as a motivational speaker. He was hailed as a reformed mentor in a neighborhood where the crime rate is twice the citywide average; where in 2018 the life expectancy of a baby was 11 years less than a baby born on the Upper East Side. He said he worked with police in a program to collect guns around the rec center, getting them off the streets. “I’ve gotta live here,” he said. “I know where to draw the line. They don’t mind shooting the s— out of you out here. I know better.”

What he didn’t know, though, would ultimately doom him. As Williams walked the sideline in Brownsville that day four years ago, police were just opening a probe into a heroin-trafficking operation around the rec center. The U.S. was (and remains) in the throes of an opioid epidemic, and here authorities pegged the local hoops legend—a man who told young ballers to eschew the street life—as a profiteer.

Still, he preached about protecting the youth. “They call this the safe haven of Brownsville,” Williams boasted of the rec center, the facility to which he drove each day from his doorman building in a leafy section of Queens, two blocks from Donald Trump’s childhood home.

“Nothing happens here. Nothing.”

***

Loretta Williams stands outside a six-story, red-brick public housing complex and cranes her neck upward, trying to retrace her brother’s fall. It was from a second-floor window in Apartment 2B, a mile north of the rec center, that three-year-old Fly was watching for the watermelon man’s horse and buggy to come down Stone Avenue—which, back in the 1950s, was still a dirt road—when, anxious to spot the peddler, he inched closer and closer to the window … until out he tumbled. “He didn’t [fall] because his big ol’ feet got stuck,” says Loretta, now 73. “I reached out and pulled him back in.”

Back then Fly was (and remains to family) “Junior,” the youngest of six children to Annie Ruth Williams, who moved to Brooklyn from South Carolina just before the Brownsville Houses popped up, in an era of white flight, civic abandonment and massive public housing construction. In the summer, with no air conditioning, the siblings would sleep outside on beach chairs. No one bothered them, but Fly, a restive, streetwise child, often found trouble, and Loretta, his babysitter, found him difficult to mind. “We would go to Coney Island,” she says, “and he would always get lost. I’d go to the precinct to pick him up. He was funny, an all-time character. ”

Brownsville—home to the mafia contract killers of Murder Inc. in the 1940s—was the type of place where it was easy for a character to find trouble. Early on, Williams picked up a job from the old guard. He would sneak out after midnight and help move cigarette trucks that had been hijacked from Idlewild Airport. When Annie Ruth found those earnings in Fly’s bedroom, she asked where the money had come from. “I told her I’d put in work,” Williams says. “I was not to be trusted.”

With growing guile the boy managed to steer clear of roving gangs like the Jolly Stompers (picture: The Warriors), but still he bore witness to stabbings and, he says, robbed delivery men. It was from this vise that basketball offered him the first opportunity to escape. Rodney Parker, a ticket scalper and talent scout, guided Williams away from James Madison High, where he was a highly-regarded wing, toward Glen Springs Academy, 275 miles northwest of Brooklyn. There he earned a high school degree and a shot at a college hoops scholarship. The canal feeding Seneca Lake, the scenic pastures, the hippy vibe—it all felt wide open after a childhood in Brownsville’s brick-and-concrete confines, even if home proved impossible to completely leave behind.

Back in Brooklyn, after Williams’s All-America senior year, an assistant from Austin Peay tried to recruit Fly to come play in Clarksville, Tenn., but pinning the kid down proved problematic, and so the coach spent a night crashing at his house, waiting. After Annie Ruth fell asleep, the coach rewound the apartment’s clock every few hours to keep the boy out of trouble, were his mother to wake. Eventually, after 3 a.m., Williams returned—to which his visitor joked: “You stay pretty busy, I understand.”

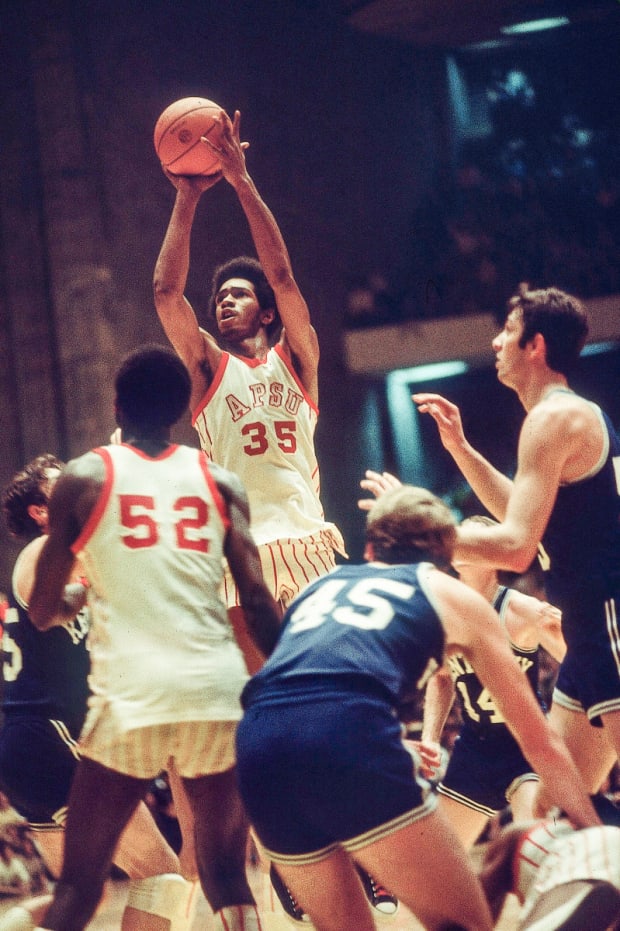

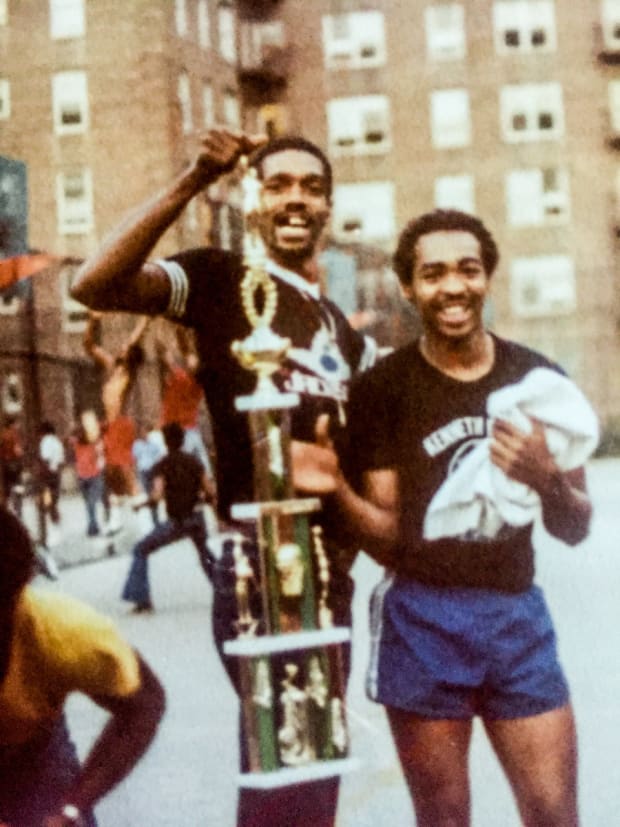

Williams followed his suitor south, toward a bandbox known as the Little Red Barn, just west of Nashville along the Cumberland River. And there lines would form to watch “Flatbush Fly.” In 1973 he averaged a freshman national-record 29.4 points—twice he broke 50—and drew attention, too, for his tantrums, once lying down on the court to protest a referee’s call. Opposing fans held up fly swatters. Supporting ones shouted, “The Fly is open! Let’s go, Peay!” and lifted him on their shoulders as he took the Governors to the NCAA tournament, hitting a game-winner against Jacksonville and pushing Kentucky to overtime before capitulating.

Williams returned a year later for an encore—27.5 points per game, another tourney appearance—and then was sent packing, on account of an Ohio Valley Conference investigation into entrance requirements.

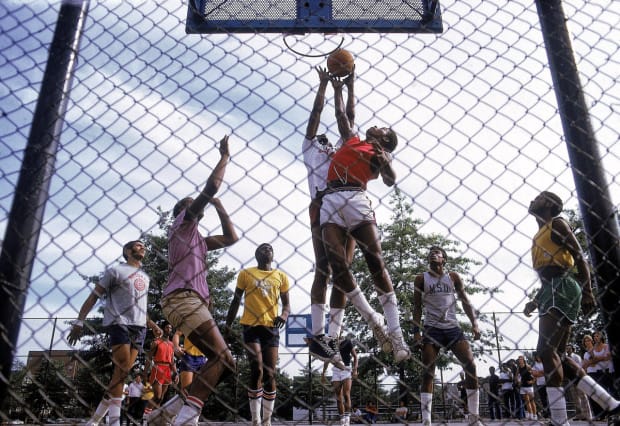

He spent the summer of 1974 playing schoolyard ball and driving a Cougar around Brooklyn without a driver’s license, all of it chronicled by Rick Telander in his book Heaven is a Playground. That September, Fly signed a $250,000 contract with the Spirits of St. Louis, teaming with Marvin (Bad News) Barnes and Maurice Lucas, a combustible crew. He roomed with Barnes, and cocaine became their drug of choice as they enjoyed the spoils of professional ball. In the end, Williams proved too unruly even by the rollicking league’s standards. He was cut after that first season by coach Rod Thorn. But, really, Fly never left the team. He’d spend the next season jetting back and forth between New York and St. Louis, providing Barnes with coke.

“They wanted the candy,” Williams says. “I was the drug guy.”

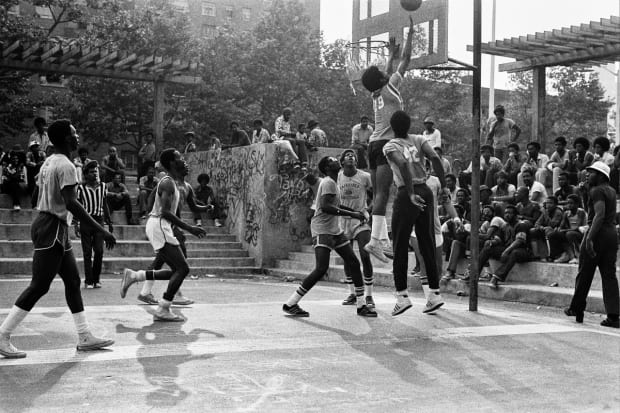

Still, Williams kept his dribble alive, running the floor from Alaska to Israel to New Jersey, where he was suspended in 1978 for striking a CBA referee and then, for his final act of theater, wrestled a 600-pound bear named Victor at halftime of a Jersey Shore Bullets game. Victor won and Williams, bottomed out, returned to the Hole, a sunken court in the center of the Van Dyke Houses, across the street from his old Brownsville apartment. And there his legend continued to grow. One story has him scoring 100 points in a park game: 55 in the first half and 45 in the second, after switching teams.

Jerry Reynolds moved to that neighborhood in the late ’70s, into an apartment overlooking the Hole. At 14 he observed the old playground legend from his window, and later he would take Fly on at street level. Williams, he remembers, elevated higher than most. He would score 50 points, then leave before the game ended. And Fly’s most impressive maneuver? The fadeaway.

“Like, where was he going?” Reynolds, now 57, wonders of that shot. “Seriously, where was he going?”

***

“Streets is in the hood!” came the call, urchins announcing Fly’s arrival back on the block as the ’70s gave way to the ’80s. “Streets is in the hood!”

Flush with cash from illicit gains, Williams would leave $100 bills in babies’ cribs, ingratiating himself upon his return to Brownsville. At night he would show up late for park games, leaving his brown Rolls-Royce in the middle of the street, dip-walking to the court, a woman under each arm. “I never warmed up; I showed up right at tipoff,” he says, decades later. “My warmup was going out there and warming your behind up.”

Sean Powell knew all about this brio. He can trace his relationship with Williams back to childhood. They used to go on training runs west along Eastern Parkway, from Brownsville to the Brooklyn Museum, and later they played together on the Bullets, earning as little as $100 per week. Once, in Maine, Powell watched Williams drop 44 points in consecutive games. “They called him the .44 Killer and Son of Sam,” Powell says. “Wild days.”

Decades later, Powell keeps a highlight reel in his head: Williams getting the ball in the right corner against the Maine Lumberjacks. Faking left. Driving baseline and dunking over defenders. Absorbing their blows and slaps. Referees huddling. And Williams calling out, “Give [the foul] to all of them! They all fouled me!”

In the end, the two friends took different paths. Powell entered the police academy in 1985. Williams was already dealing drugs by then, and one day, as the young officer walked to work in his baby blues, Fly approached. “Sweet daddy, get in the car, baby,” he said. “I’ll take you around.”

“I love you,” Powell replied, “but if we get pulled over, it all goes down the drain.”

Williams was already spiraling. On his worst days he would retreat to the corridors of Noble Drew Ali Plaza, another housing complex, a block from the rec center, and with a butane torch he’d vaporize cocaine in a glass pipe. A hyper-consumer, he freebased and sang along to “Strung Out” and sold coke in hand-to-hand combat. As the gyre of urban decay widened, Plaza residents abandoned their apartments and Williams took control of six units before largely withdrawing from social interactions. Mike Tyson, another Brownsville product, once stopped by. Williams refused to see him.

In February 1987, following a game in Starrett City, Fly was trying to rob an old running mate, James Ryans, when an off-duty court officer intervened and shot Williams in the back. Fly admits he was high at the time (“acting a fool,” he says) but maintains there was a “misunderstanding.” Afterward, Loretta cleaned her brother’s grapefruit-sized crater of a wound. “The boy had nightmares,” she says of his recovery. “He couldn’t sleep.”

In January 1994, Williams was incarcerated for drug possession, and he spent the next three years in New York state prisons, as well as at a treatment facility. Afterward, he set to mending his relationship with the community, including with Gregory Jackson, an old Brownsville friend who’d taken over the rec center in 1997. Jackson had Williams talk to the neighborhood kids about hard-learned lessons, and even Fly says that he saw then the folly in this approach. “I told [Jackson],” he says, “ ‘Man, I ain’t Jesus Christ.’ ”

Basketball fame, though, works in funny ways, and in certain circles Fly remained a hoops god. He appeared in a 2003 Nike commercial, LeBron James’s first. There were Julius Erving, Jerry West and George Gervin, sitting at a church altar, Williams relaxing in the front row, one leg crossed over the other while Bernie Mac orated. Williams’s street cred was a brand. “Got me a nice check for that,” he says.

There was even a rebirth moment. In 2010, Williams was rushed to the Jewish Medical Center on Long Island after suffering a heart attack. Powell found his old friend entangled in tubes, and a doctor spoke up: “We lost him.

“… But we brought him back.”

That wasn’t even the climax. For absolute affirmation that—outwardly, at least—Fly Williams had turned everything around, had reinvented himself, you had to be at the Barclays Center on Flatbush Avenue in February 2014. There was Williams, at halftime of a Nets-Bobcats game, wearing a black Kangol hat and dark fur coat, a Brooklynette on each arm, accepting a Black History Month award. T-shirts were made. Telander was flown out.

In the end, Williams walked away with a plaque declaring him an “ordinary” person “doing extraordinary things.”

***

A painted human skull with bulging blue eyes and chipped teeth—six feet up, four feet across—greets guests today at the Brownsville rec center gymnasium. All around, 53 basketballs appear to be bouncing out of its mouth.

To the left is Williams’s mural, life-sized and capturing the height of his career, when he was long and lean, his hair shaped in an Afro, dribbling with the Spirits. To the right is a likeness of Saquan Thompson, another local star, at Bishop Loughlin High, who at 18 was shot dead right in the middle of a Brooklyn street in 2010. He, too, is depicted in uniform, performing a finger roll. Below him is painted: FOLLOW YOUR DREAM.

Going back to the early 2000s, Williams oversaw a tournament for the neighborhood teenagers called FLY: For the Love of Youth. He’d hand out red T-shirts printed with a list of positives (basketball, education …) and negatives (guns, drugs …), and he’d lecture the kids in his own snappy, quotable way. “When you take a life, you get 25-to-life. … The police got the biggest gang in New York. … You gotta stop doing what you’re doing.”

But Williams’s own criminal record grew even during this time of reconciliation at the rec center. According to police records, he was arrested for criminal possession of a controlled substance in 1987, ’92, ’97, 2000 and ’13. In June of ’16—at a time when the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimated that some 350 people were starting on heroin every day in the U.S.—detective Brian DePalo was working with Brooklyn North’s major case unit, looking for his next undertaking, when he learned from a confidential informant about a heroin ring operating in Brownsville. DePalo deployed undercover officers to penetrate the enterprise and quickly learned that Williams and his stepson, Jeffrey (Doobie) Britt, were major players. Suppliers worked out of the Bronx, stashing bags of heroin inside emptied cans of aerosol Fix-A-Flat; and rank-and-file dealers—“Voodoo,” “Moe Joe,” “Mike Mike” and “Shorty,” as well as Fly’s son, James Jr.—peddled glassines stamped with stick figures, priced between $6 and $10 apiece. Surveillance captured denizens approaching dealers on the street “like a cheese line,” says DePalo.

Wiretaps went up and cops heard Williams boasting about his territory: You’re not going to sell dope on this corner when I’m on this corner. … I see you; you hesitate, your ass mine. … My gun gonna do the talking.

According to court documents, Williams talked on one call with a girlfriend known as “Baby Girl” about stashing that gun in a car parked by the rec center where he mentored. Later, after he was hospitalized due to complications with blood thinners, his wife, Carol, discussed with Doobie the idea of accessing Fly’s cash.

Carol: “I was telling you to get a key to his house. And when [he dies], you get some of that money.”

Doobie: “I don’t give a s— about that money. He can keep that money. He want it so bad? Let him take it to hell with him.”

Armed with a no-knock warrant, DePalo and his officers finally broke down Williams’s door in May 2017, shortly after he’d turned 64, and rousted him out of bed around 6 a.m. Among the mix of evidence and mementos they found inside: a 9mm pistol loaded with 10 rounds; 32 glassines of heroin; and a framed poster from the night Austin Peay retired Williams’s no. 35 jersey, in ’09.

Anthony Boggan grew up in and around the rec center, and he remembers Williams imploring him as a kid to get out of Brooklyn. Eventually, Boggan did; he played college ball at Division II Saint Augustine’s in North Carolina before enlisting in the Navy. When he heard of Williams’s arrest, he cried. “Really hurt me,” he says now. “This gentleman told me to stay on the straight and narrow. I looked up to him.”

Police, who called their probe Operation Flying High, announced their findings in a press conference. The ring, they said, was worth $21 million and had sold some two million glassines. Kings County District Attorney Eric Gonzalez dubbed Williams and his cohorts “the worst kind of drug dealers.” (Separately, DePalo maintained that Fly had never helped in any gun-collection initiative. He also noted that, for all of Williams’s showy displays in the past, he behaved decidedly “old school,” driving a beat-up black 2003 Ford Expedition between boroughs while under surveillance. “There wasn’t anything flamboyant about his lifestyle,” DePalo says.)

In court, Fly and three codefendants faced the state’s kingpin statute, with a mandatory-minimum 25-year prison term. Williams recognized that a conviction would likely have him die in prison, and he argued instead that he’d only operated in an advisory role. After his first two bail requests were denied, he fired his attorney. He hired a second lawyer and maintained his innocence for more than a year, convalescing, meanwhile, on Rikers Island, where his daughter, Sharita, is a corrections officer. He insists to this day that he never sold drugs in the rec center, or to children, and that he never used fentanyl in his product. (According to DePalo, no overdoses were ever traced to the ring.)

Finally, in June 2018, after Doobie and James Jr. secured their own plea deals, Williams pleaded guilty to “overseeing” sales of a controlled substance, conspiracy and firearm possession. Two weeks later, on the day he was sentenced to eight years in prison, Loretta and her six-year-old great-grandson, Jamel, were Fly’s only supporters in court. Afterward, they rode the subway back to the Brownsville Houses, where another sister, Irene, still lives in their family’s old unit.

Back at the apartment, Jamel asked: “What did [Fly] do wrong?”

“He sold drugs,” Irene said. “You know how people get that shoot-up in their arm? That’s bad juice.”

Jamel looked down.

“I teach my kids when they are young,” Irene said. “Not when they are old.”

***

If you travel from Brooklyn, little red barns dot the farmland as you approach Attica, N.Y., a two-prison town just east of Buffalo and best known for an uprising at the maximum security unit. Across a driveway sits the Wyoming Correctional Facility, where Williams ambles into a visitation room. In his pants pocket he carries two passes. One excuses him from strenuous activities. The other allows him to bypass metal detectors. Gone is the arrogant gait. Now he wears a graying beard.

“I’m always going to be the bad man,” he announces. “I always was the bad man, even on the court. Look at the bad guy!”

Williams, who today is more than two years into his sentence, sits down at a square table. On the front of his green state-issue shirt he is inventoried as inmate No. 18A2578, but his street name, Fly Williams, is printed in black.

“Everybody goes to the same tailor here, man, but real people do real things, and I’m real people, man,” he said. “Play my I.D. number in the lottery. It’ll pay.”

By turns, he is comical and elegiac, farcical and tragic.

“Everybody’s in trouble, even the president, so I don’t feel bad,” he says. “Bill Cosby, America’s dad, in jail? I’ll be damned.”

He expresses no regret for his myriad crimes, but he wonders what his mother would tell him if she were around today. When Annie Ruth died in 2007, at 91, Fly paid for the funeral, but he couldn’t bring himself to stay in the church. He broke down crying. He has not dealt with death well, he says, since that day in his 20s when he came across the body of a boy he knew as Collard Greens, lying lifeless at the corner of Saratoga Avenue and Dean Street.

“I’ve had a damn good life. I fulfilled my dream,” he says. But even after the ABA there was always that pull back to basketball, and to Brownsville, with all that came with it. “I just didn’t want the light to go out. You go back to do what you know when you need to survive.”

He stays in touch with friends on the phone and with a pen. In one letter to Powell, who retired from the police force and works in security at a hospital on Long Island, Williams reminisced about old runs at Rucker Park, writing: “I think of Harlem all the time. … Some [inmates] know of me but never seen me play.” A recent missive ended with an optimistic note:

Pray for me. It’s a new year. It’s going down. Be home before you know it. Hold on. I’m coming.

Love is love,

Sweet Daddy

The Fly 35

Back at the rec center, a world away, his specter is still present, but changes are coming to his old haunt. Renovations are planned; designs call for more natural light, new classrooms and a refurbished gym. Williams wonders what it will look like, and he envisions returning someday. On a neighboring street, he knows that a friend sells $6 T-shirts emblazoned FREE FLY, with an orange basketball depicted behind prison bars. He believes that, were he to return to the center, he could quickly regain trust.

“Everybody knows I’m in here because I didn’t tell on nobody,” he says. “My daughter wants me in a rocking chair with dogs far from New York when I get out. That’s not me, though.”

He rolls up his left sleeve to reveal a tattoo on his forearm. He has a matching one on the back of his neck. They were supposed to be flies, but he thinks they more closely resemble cockroaches. He shakes his head.

Williams is undergoing anger management, and each morning he performs what he calls a “Jane Fonda workout.” He unfurls a CVS-length receipt from the commissary that lists recent purchases: fried chicken, Egg Beaters, grits and Newport cigarettes. “I’m trying to stop,” he says.

In the end, he insists, he’ll walk out the same way he walked in. Sometimes he forgets the route, though, and as his visitation period ends he looks toward an officer by the door.

“Which way?” Williams asks.

To the left, light filters in through a door. He steps toward it.

“No, you don’t want to go there,” the officer says. “… Well, you do. You just can’t. Not yet.”