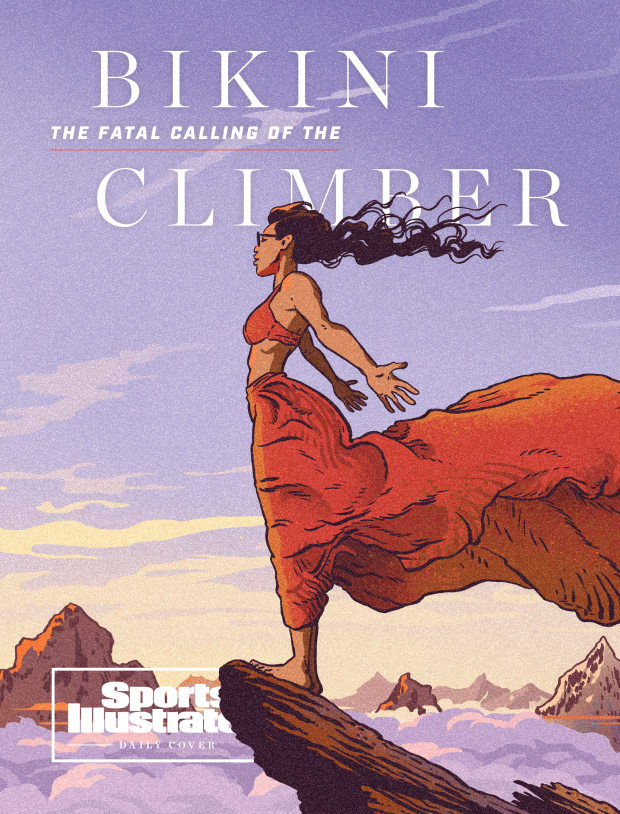

Taiwan’s highest peaks gave her solace and purpose—and they carried her to swimsuited social media fame. But the mountains got something from her, too.

When Gigi Wu was alone in the mountains she usually rang a friend around 6 p.m. She would let him know that miles of slick and jagged terrain were behind her. That she had finally freed herself of her 65-pound pack and was preparing to settle on a flat patch of earth for the night. That she would soon prepare her tea and rice, just as the stars started to shimmer.

But on a cold Saturday afternoon in January 2019, Alex Yang’s phone rang at 4:30. Too early, he thought. Too soon.

Yang, a 52-year-old construction materials salesman with flecks of gray in his dark hair and a long, symmetrical face, took the call in his Taipei office. Wu, famous on social media for summiting some of the most menacing mountains in Taiwan—and, more pointedly, for posing at the end of each climb wearing only a bikini, the pics of which populated her Facebook page—was ringing on the satellite phone that Yang had bought her so she could stay tethered to the world during her increasingly dangerous solo sojourns. Wu, 36, typically spoke with a measured rasp, but now her words seemed hurried through the static. Over a frantic 30 seconds, as her voice faded in and out, Yang deciphered that she had tumbled down a cliff and couldn’t move her legs. She needed help.

Wu begged her hiking friend to remember the article they’d recently discussed. The one about a trail that long ago connected villages inhabited by Taiwan’s aboriginal people, but that had gone untended and largely unused as far back as 1895, when Japan took control of the island. Remember that trail?

He did. He also knew that temperatures in those mountains would likely dip near freezing at night. Yang told her to stay warm—and then the call fell dead.

His mind churned. Wu’s voice conveyed a sense of urgency but not fear. He knew she kept the phone in her pack; her gear and food must be within reach. Besides, she had thousands of miles and hundreds of summits behind her. She was too experienced, too hearty, to succumb.

As Wu lay alone, Yang rushed to relay the call’s coordinates to authorities at Yushan National Park, which spans 260,000 verdant acres across the middle of Taiwan. Then he tried to call his friend back. Every five minutes. Again and again and again.

Deep into the night he texted updates and reassurances, with no response. The local fire department was summoning rescue hikers. Helicopters would be coming. Her saviors would surge through the mountains to extract her.

Stay warm.

***

Gigi had been the only person at the bedside of her 63-year-old father, Sheng-cin, when a stroke felled him in April 2014. That day she lost the man who opened his heart to the Persian cat, Peggy, that she adopted during her brief time away at technical school. Who swam with her in the river near her grandparents’ home when she was a child. Who showed her how to forage for snails on the river’s banks, back when her hair was cropped boyishly close, not grown long enough to billow on breezy mountaintops.

When Gigi’s employer, an international trading firm, asked her later that year to move to China, she took stock of her life. Her older sister, Yu-chi, had married and moved out of the family’s modest fourth-floor flat in New Taipei City; her mother, Su-ran, was in her 60s and grieving. It was with this in mind that she quit her job, stayed home and directed the savings she’d amassed throughout her 20s toward a hobby that provided an escape from this profound new pain.

Gigi first encountered Alex Yang in 2014 on Jade Mountain, home to the highest peak in Northeast Asia, at 12,966 feet. They embarked on that trip with a climbing group organized by a travel agency, then bonded over their love of photography as they ascended. Still, Yang was shocked when, at the summit, his new friend shed her gear, down to a swimsuit top, and set up a photo shoot.

Wu explained a challenge and a dare. She was trying to conquer the 100 Peaks of Taiwan, a group of mountains, each at least 3,000 meters (or roughly 10,000 feet) above sea level, that are deemed to be the most demanding on the island. And at some point along the way she’d lost a bet with a friend, the payout being that she had to pose in a bikini top when she reached her next summit. Eventually, what started out as a dare for a slender, demure girl who had grown up hiding behind glasses turned into a tradition for a 5′ 6″ young woman learning to lean into her beauty and her bravery. In the early mountaintop photos Wu posted to Facebook, her hair was stringy and unkempt. Unflattering, baggy hiking pants hung from her hips. As months passed, though, she pulled on increasingly vibrant swimsuits, her hair grew longer and straighter, her poses turned more provocative. And with each photo she attracted more attention, more followers.

To some, the whole endeavor seemed a vanity project: sensationalism in a sacred space. But those close to her saw a devoted hiker using her allure to promote and preserve the mountains’ beauty. On Facebook, Wu captioned her bikini photos with details about the routes she had taken to the top and alerted fellow hikers about difficult portions of each ascent. She interspersed the glam shots with snaps of misty forests and craggy trails, translucent mountain pools and vistas hanging above endless floors of clouds. While male commenters tended to laud her body, female followers christened her a mountain goddess.

In July 2016, when Wu finally reached all 100 summits, the accomplishment drew relative renown in a country where casual sexism reigns—where it’s common for a man to critique a female coworker’s hairstyle or weight. As it does elsewhere, the male gaze has shaped how Taiwanese women are expected to present themselves. Wu, friends believe, sought to reclaim her body. What some saw as an object of lust she turned into a symbol of pride, posing only on hard-to-reach plateaus where her fortitude would overshadow her figure. Anyone ogling her had to also gaze upon her success.

It was impossible, after all, to write off her accomplishment as some simple stunt. Taiwan’s topography rises sharply from the sea, presenting a formidable challenge for even the most experienced climber. Except for the few trails the government maintains, most are laden with endless corridors of wet brush, and they tend to follow ridgelines or streambeds, making them more difficult to navigate than those that gently wind up mountainsides. Access to those paths had been cut off for decades, and when martial law on the island ceased in 1987, stringent regulation persisted, partly because the mountains had once been taken up by military strongholds. The government declared the bulk of the ancient trails off-limits to the public. Yet, as Wu’s mountaineering savvy grew, so did her inclination to sidestep sanctioned routes and push the archaic boundaries that Taiwan’s hiking community had for years lobbied the government to lift.

Even then: As influencers go, Wu was small-time compared with Taiwan’s fashion and lifestyle elite, whose Instagram accounts are designed to profit from far more followers than her 14,000. Again and again she passed up opportunities to leverage her notoriety, turning down sponsorship deals from hiking equipment companies and declining a partnership with a mountain tour outfit. Even as Wu’s savings dwindled, she remained wary of letting outside interests dictate the trails she hiked or the clothes she wore. She focused her posts instead on documenting where climbers could find water or cell service. She collected trash along her trails, took on extra weight to help injured or exhausted hikers and pushed herself to explore new terrain. Yang, by then a close friend, bought her the satellite phone and a Garmin GPS. Now she was aiming beyond the 100 Peaks; her goal was to summit every one of Taiwan’s 268 mountains that top 3,000 meters.

Relatives, meanwhile, began prodding Su-ran, asking how she had lost control of her daughter. Why doesn’t Gigi work? When will she abandon these adventures? And at home those conversations devolved into disputes. Gigi flitted in and out of their shared flat, only occasionally calling to ask her mother to make extra food for dinner. By 2018 she was spending nearly as many nights in the wilderness as she was in her bed.

On the mountains, too, a similar distance grew. As Gigi gained experience, fellow hikers struggled to keep pace, slowing her progress. She squabbled occasionally with friends over which trails to pursue, and to avoid those tensions gravitated toward solo outings, a dangerous undertaking on unfamiliar trails. In May 2017, she set out alone across the Central Mountain Range before turning back, noting later online that a mistake made while hiking solo “can be your last.” A year later she posted a photo of her legs, scarred and bruised from a dangerous fall that she said almost took her life.

Near the end of a three-week trip in December 2018, she rejoined her fellow hikers for a party at one of the massive cabins scattered along the country’s sanctioned trails. Some 150 people mingled there and in the surrounding campgrounds, and Wu bounced from group to group, engaging with those who wanted her and those who idolized her.

Camped on the edge of the party that night was 55-year-old Jon Solomon, a Massachusetts native who since the ’80s had been hiking the country’s toughest mountains. Solomon is an advocate of “ultralight” hiking; he aims for a slight food and equipment load, which helps him keep balance on Taiwanese trails frequently made soggy and slippery by subtropical jungles butting up against alpine forests. And when he ran into Wu the next day during one of her elaborate photo shoots, he was astounded by what she carried. Before setting out on a trip she and Yang would weigh her pack. For longer journeys the goal was to stay below 70 pounds—more than double Solomon’s typical haul.

Solomon and Wu traded notes that afternoon, and he encouraged her to lighten her load. She showed him her sustenance: candy bars that provided relatively little fuel for their weight, plus rice and noodles that required bulky cookware and, on occasion, extra water. He recommended swapping the candy for dehydrated meals. More concerning to Solomon, though, was the substantial equipment Wu had carried for her summit photo shoots, including a Canon 5D Mark III camera (about the weight of a pineapple), a pair of large lenses and an unwieldy tripod. Perhaps she could settle for less cumbersome gear? If she lost her balance, a light pack—one better proportioned to her body mass—was less likely to overpower and tug her down the mountain.

No one else at that mountain gathering, Solomon recalls thinking, would be inclined to offer such advice to Taiwan’s most famous hiker, but he tried.

Nearly two years later he still recalls how Wu cut their conversation short, politely waving off his suggestions, and stepped back in front of her camera.

***

On Jan. 11, 2019, after riding three trains and a bus, then spending a night in a cheap hotel favored by hikers, Wu hit the trailhead on a two-week trek through Yushan National Park in Central Taiwan. Her pack was laden with photo equipment, plus the food Yang had helped her purchase: bread, cheese, meat, coffee, rice milk, pineapple cakes, noodles . . . . She planned to start on the Batongguan Historical Trail, a familiar path, but then deviate (without an official permit) onto an unsanctioned and perilous aboriginal trail that neither she nor her hiking buddies had ever attempted. Her route would be a circuit, beginning and ending at the Dongpu hot springs to the west of the mountains, where Yang planned to pick her up on the 24th. On the first day of her hike Wu came upon a dead dog inside a mountain cabin, and carefully carried it outside.

Before setting off again, Wu consulted a weather report. The skies, she read, would be clear on the 18th and the 19th, which looked to be two of her journey’s most arduous legs. On the first of those days, right before she planned to split off onto the aboriginal trail—descending the northwest face of Jupen Mountain, a 10,223-foot peak—she posted a picture on Facebook: a blanket of clouds captioned CELEBRATING TODAY.

On the 19th, Wu veered from any clear trail. Her route was a vestige of an old one, her boots crushing wide swaths of shale and detritus from the thick canopy of trees. The terrain would have demanded that she negotiate the steepest descents using her hands to brace against tree trunks while keeping her footing in unceasingly damp conditions.

The weather reports, though, had erred. Conditions worsened with every hour. Around noon Wu messaged another friend who had helped her map out a route. She had reached an altitude of almost 8,000 feet and planned to push down closer to 5,000 before setting up camp near a small river at the base of two long ridges. When she arrived she promised to let him know she was safe.

That friend says he never heard from her. Instead, at 4:30, Yang’s phone rang.

By the time he took Wu’s distress call and relayed the coordinates to park authorities—who in turn relayed them to the Nantou County Fire Department (typically tasked with mountain rescues) and then to the National Airborne Service Corps—the day had grown too late and the weather too poor to send out help on foot or by air. A new forecast suggested the skies would clear early in the morning. And while the temperature was predicted to dip overnight, it wasn’t expected to fall below freezing.

At dawn, though, the rain kept coming. With the helicopters grounded in the fog, Lin Cheng-yi, a 38-year veteran of the fire department’s Third Squadron, called upon volunteers from the Kalibuan, a segment of Taiwan’s aboriginal Bunun tribe that tends to live at high elevations. Adept hikers, the Kalibuan often work as mountain guides for travel companies, and many of them help when a hiker goes missing.

At 8 a.m. on the 20th, a firefighter and two Kalibuan, including a 52-year-old tribesman named Buaq Soqluman—bare-scalped and stout—hopped into the bed of a blue pickup truck. They began ascending gravelly mountain roads in hopes of rescuing a woman who once posed for a picture with a member of the Kalibuan tribe when they crossed paths on the trail, and who had photographed their remote mountains to share that beauty with the urban masses along the coasts.

Armed with Wu’s coordinates, plus food, tents, clothing, ropes and a portable stretcher that could be hooked to an airlift rig, the Kalibuan traversed a mountain road up to 8,200 feet, the closest they could get to her last known location, before setting off into unfamiliar terrain on foot. Another team of three men—two Kalibuan and a firefighter—hung back, hoping they might be able to get closer to Wu by helicopter. But the fog and the rain lingered, so they, too, set off by foot, around 1 p.m.

That afternoon, 100 miles to the north, police knocked on Su-ran’s door and described a scenario she had never allowed herself to consider. Her daughter, the expert hiker, was in danger.

***

After barreling down slick slopes for hours on end, 45 pounds of equipment strapped across each of their backs, the first rescue team finally reached an altitude around 5,000 feet, near the coordinates Wu had relayed to Yang. They knew she had been alive at least within the last 28 hours, roughly, and as night began to blanket the mountains, they believed they had found her. Well below them, Soqluman says, a mass—maybe a body—rested among a cluster of hiking equipment on a narrow platform jutting out from a cliffside that descended hundreds of feet to a river.

A fall to the bottom would have meant certain death. But it appeared Wu had been lucky enough to land on that flat outcropping of earth after a 100-odd-foot tumble. Soqluman called down, but his cries drew no response, no movement. The mass below them lay quiet and still in the darkness.

Rain and poor visibility made it impossible to descend the cliff face that night. Temperatures again dropped, just above freezing, too wet and too cold to start a fire, so Soqluman says the men retreated to their tents and waited, anguished, for dawn. The next day they rigged ropes to the cliffside and over several hours navigated a path down the steep slope laden with trees, wet leaves and stone.

Wu was lying on her back, eyes closed and mouth bloodied, when Soqluman reached her that morning. No breath. No pulse. Skin cold to the touch. Her backpack had settled near her, a satellite and cellphone by her right side and a flashlight tied to her left wrist. A silver aluminum sleeping pad covered most of her body, but her jacket was laid out next to her—perhaps odd to a hiking outsider, given the night’s chill. Debris from food and drink littered the ground.

Without cover from the rain and cold, Soqluman surmised, she must have died the night after her fall. She was wearing hiking clothes, but the material was thin. As the cold gripped her, and as she was unable to dig the tent out of her backpack, moderate hypothermia would have induced amnesia and lethargy. Eventually, she would have ceased shivering and felt warm, accounting for the cast-aside jacket. As her condition worsened she may have hallucinated, perhaps explaining the toothbrush that seemed to have been carefully placed by her right hand. She might have believed she was settling in for another night’s sleep in the mountains, no different from all the others. Her heart rate and breathing would have slowed. A coma would have followed. Then death.

The Kalibuan couldn’t determine what had caused Wu’s fall, but vanity didn’t seem to have been a factor. Her camera equipment was tucked neatly in its bag. The rescuers found her identification in her backpack, then reported her death to the fire station. Receiving the news, Lin wished they had found her in time, but he understood that others could have died if they had challenged nature more aggressively.

Owing to the uneven weather and the location of the body, it would be another two days before a ground team and a trio of helicopters could begin extricating Wu from her resting place. Rescuers first had to chainsaw three trees to create clearance for the air unit. Finally, on the morning of Jan. 23, a UH-60 Blackhawk hung 200 feet above Wu’s corpse for an agonizing 38 minutes, the pilot holding the craft steady against wind cutting down from the mountain while a team hoisted the body onto a metal stretcher. An orange bag concealed Gigi from view. The aluminum hiking mat remained draped over her, flapping in the rotor’s wash.

For Johnny Chiang, the rescue team’s brigade commander back at base, the recovery proved the most arduous of his 32-year air-rescue career. Ultimately, he was sorry he was unable to save the woman who snapped one of his favorite pictures, capturing a chopper as it hovered over Jiaming Lake, along the park’s southern border. Days later, he would place the photograph in Wu’s coffin.

***

After the Kalibuan made their grim discovery, the news spread first among the dozen journalists awaiting word of Wu’s fate at the primary school that her rescue team had used as its base of operation. Soon, though, the rest of the country knew.

In Taipei City, Su-ran had retreated to a Buddhist and Taoist temple after the police first showed up at her door; when she finally emerged from her prayers, a friend told her what everyone else had already learned.

Solomon, a month removed from his encounter with Gigi, was in Hong Kong when he heard of Wu’s death. The news rattled him, but he wasn’t shocked, given how she’d rebuked his gentle warning.

Thousands flocked to Wu’s Facebook page, which turned into a memorial, loving goodbyes interspersed with photos of the climber wearing bright swimsuits atop the mountains she had conquered. Admirers praised her for spurring interest in climbing among her countrywomen, for exemplifying the inner strengths they themselves may not have realized, for being a role model to young girls who might not otherwise have strived for anything beyond physical beauty.

Alongside the praise, though, were harsh criticisms. Commenters suggested she had perished in a shallow pursuit of fame. Some incorrectly surmised that she’d been hiking wearing only a bikini—of course she froze to death, they chided. Headlines across the world, meanwhile, framed her as Taiwan’s glamorous BIKINI CLIMBER, not an experienced mountaineer. Based on a persona that sprung from a dare, Wu was hastily lumped in with a small subset of social media risk takers who have died chasing clout, and with the hundreds more people around the world who have perished mid-selfie over the past decade.

Su-ran was stung by those scathing words, including some from family members, who insisted she should have done more to rein in her daughter’s dangerous pursuits. The Taiwanese government weighed in, too, threatening to fine Su-ran $60,000 because her daughter had been hiking on an unsanctioned trail when helicopters and a cadre of climbers were marshaled to save her. In the end, Gigi’s climbing friends intervened, and the government relented.

In New Taipei City that January, 300-odd people attended Wu’s funeral, many of them hikers who’d traveled from far corners of the island to stand in a room overstuffed with mourners. They filled a memory book with messages of love and support, and Yang played a video capturing his friend’s transformation from a little girl who’d frolicked in rivers to a revered mountain goddess.

After Wu’s cremation, friends placed her ashes in a small box, which they deposited into a shallow hole under the shade of a fir tree in a southeast New Taipei City cemetery. A small stone, largely indistinguishable from others around it, would mark her grave in the most pristine portion of a vast burial ground carved into a hillside and often blanketed by mist in the winter.

One climbing friend, Rhode Lo, says he quit hiking for six months after Wu’s death. Yang says he rarely ventures into the hills anymore. Without Gigi to provide color, the mountains seem muted.

Wu’s old bedroom remains untouched; her hiking journals lie about, alongside memorial messages from fellow climbers. Su-ran lives alone now, but her daughter’s extended family works to stave off the loneliness, whether it’s a phone call or a shared meal. Lo sometimes will walk with her through the misty park where Gigi’s ashes comingle with nature.

Su-ran has smooth skin for a woman of 70; the deep lines around her eyes reveal themselves only when she smiles. More often, though, she stares down for long stretches, the grief of losing Gigi overcoming her. She worries about how—if, even—her daughter will be remembered. That’s why she settled on the anonymous stone under the shade of a fir tree. Gigi left behind no children, who customarily tend their parents’ graves in Taiwan.

Wu’s legacy persists, though. A few days after her death, a former government official publicly called attention to the fact that most of Taiwan’s hiking fatalities—Wu was one of eight who died in Yushan last year—were unregistered adventurers, many of whom had fudged their itineraries and traveled on forbidden trails to skirt onerous regulations, making search and rescue operations more challenging. The government responded by urging better mountaineering and wilderness education, and officials started drafting amendments that would require warning signs be placed in dangerous mountain areas, absolving the government of liability in accidents.

Finally, last October, the country’s prime minister, Su Tseng-chang, announced a monumental shift, which media and mountaineers credited to the awareness raised by Wu and later by her death. The government would lift access restrictions to the forests and mountains that had existed for decades, and Taiwan would invest nearly $23 million to restore 78 trails, renovate 35 cabins and improve route signage. Crucially, more cell towers would go up, helping imperiled hikers like Gigi maintain contact with the outside world.

Soqluman spent his youth hunting in those mountains. His livelihood now depends on them. And he welcomes the chance, finally, for others in his country to interact freely with that territory. When he and his fellow rescuers reached Wu’s body on that cliffside platform, they stood in silence—trees rustling around them, river bubbling hundreds of feet below—and muttered a soft prayer before they began the delicate task of preparing her body to be spirited away.

They did not realize then the futility of their work. Even with ropes and carabiners and helicopters, they could never pull her from that place. Gigi Wu had long since given her life to the mountains.