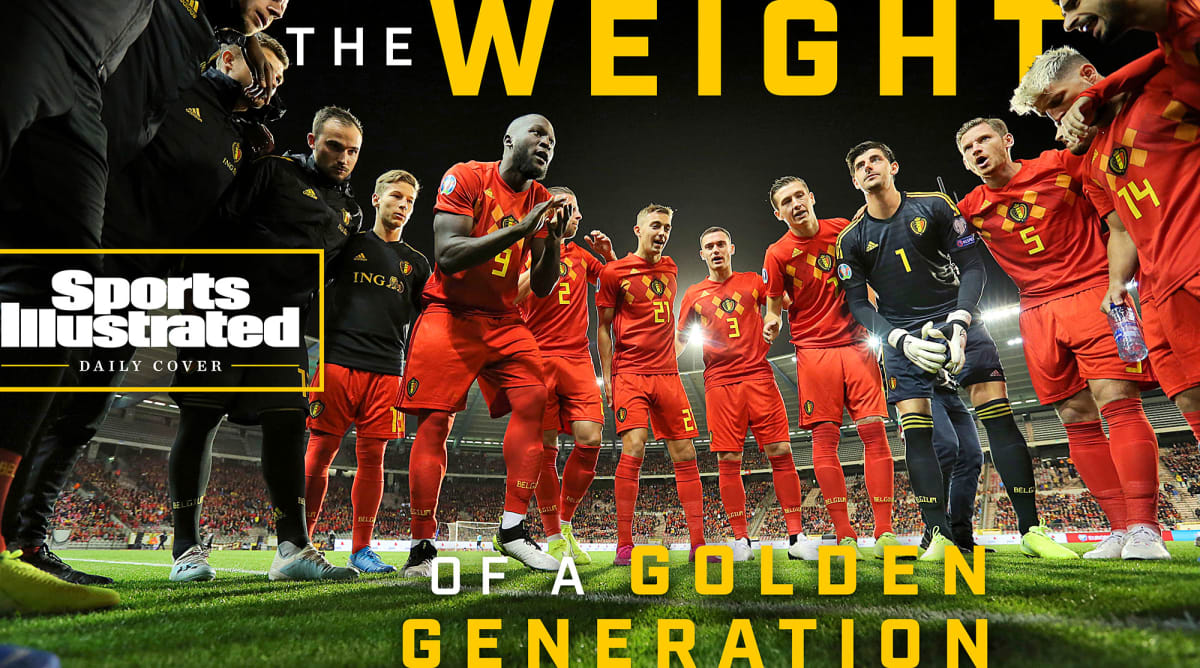

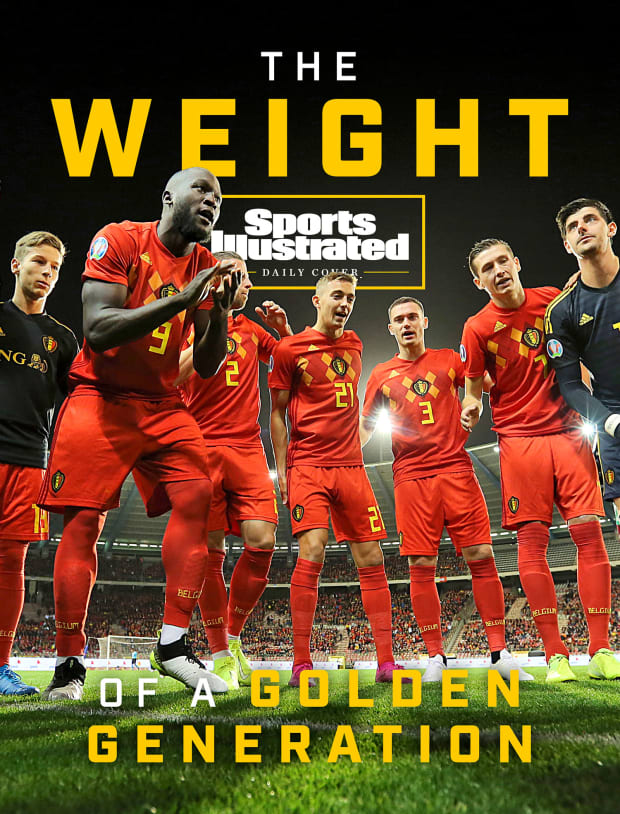

Belgium is into the latter years of its golden generation, with a World Cup bronze medal to its name. Does full validation only come in the form of a title?

Romelu Lukaku has taken part in a Europa League final, an FA Cup final and the UEFA Super Cup during his 12-year pro career. The striker has a sense for what a final feels like. And the World Cup semi between Belgium and France three years ago did, in fact, feel like a final, he confirms.

The bracket had brought together the top two teams in the tournament a step before the actual decider. On its opposite side, a decent but exhausted Croatia, the World Cup’s Cinderella, emerged. The famous golden trophy wasn’t on display as Lukaku’s Belgium and favored France took the field in St. Petersburg, Russia, that July evening, but it felt like there was hardware at stake. The game was tight, intense, edge-of-your seat theater, and it was decided by the finest of margins—just like a final.

“For us, that was a perfect opportunity to show the world how good we are as a team, and I think we did,” recalls Lukaku, 28, who’s already Belgium’s all-time leading goal scorer by a wide margin. “I think the game against France was the final, for the final, to be honest. On the day, that’s what you see in games like this—every margin counts. They scored on a set play.”

Samuel Umtiti’s near-post header off a corner kick from Antoine Griezmann was the difference, and, sure enough, France then defeated Croatia relatively easily to win its second World Cup. Belgium recovered and beat England a few days later in the consolation game, thus leaving Russia with bronze medals and plenty of satisfaction.

“People were falling in love with the way we played,” Lukaku says, comparing Belgium with France’s more efficient, cautious approach. “We played the game how the people want to see—free-flowing, attacking, many players going forward, scoring a lot of goals. We were probably the best-playing team over there.”

By one definition, perhaps—but not the one that matters to most. France added a star to its cockerel crest and is the undisputed world champion, while Belgium now resides in a strange gray area as the next big tournament, the European Championship, kicks off Friday.

Belgium played in a final that wasn’t a final, and it was the best-playing team that wasn’t the best team. It lost, but celebrated. Since September 2018, shortly after the World Cup, Belgium has been ranked by FIFA as the best national side in the world. That’s a span of nearly three years. But no trophy or title comes with that. It’s a piece of trivia—a conversation starter. Belgium is the only team that’s been ranked No. 1 (the list first appeared in the early 1990s) that’s never won a World Cup or continental championship.

The Red Devils are a juggernaut bursting with top-tier talent that hails from a small, second-tier soccer nation without much historic or recent success. Belgium is not among Europe’s “Big Five”—England, France, Germany, Italy, Spain—yet over the next month it’ll field members of a historic golden generation who dominate those leagues. The country’s population is just 11.5 million. That’s a little less than Ohio’s. Belgium is a David on steroids, clad in Goliath’s armor and wielding the giant’s weapons.

Coach Roberto Martínez, a Spaniard, recalls the post–World Cup rally at Brussels’ Grand Place. It was a raucous third-place party.

“We had an incredible celebration in 2018,” he says. “It wasn’t about we didn’t win the World Cup. We showed that we tried to win with what we believe Belgian football should represent. Obviously, beating Brazil in the [quarterfinal] helps. You see the World Cup in a different manner. But the celebration was because everyone was proud of this team, and we have so many neutral fans around the world, and I think that’s the objective of this team. This team needs to be genuine with what they represent, and they need to try to win.”

But is trying still enough? Is beautiful, technical, attacking football still enough? At what point, if ever, are moral victories no longer sufficient? What are fair expectations for this golden generation from this modest country? When does Belgium’s gray area become black and white?

Lukaku, who just won the Serie A crown with Inter Milan, is 28 and on the younger side of the golden generation. Belgium’s team has been quite stable over the past few years, and Martínez points out that only three members of the 2018 squad—Vincent Kompany, Marouane Fellaini and Moussa Dembélé—have moved on. Meanwhile, the talent pool has expanded to the point where the manager says he’s been monitoring 108 players as he plans for the Euro, 2022 World Cup qualifying (which already is underway) and October’s UEFA Nations League final four (where Belgium will meet France once again).

But it’s the cohort bracketed by the three retirees and Lukaku that has changed the status and perception of Belgian football. That’s the group that’s good enough to win but hasn’t, and it’s the group that’s starting to run out of time. The Euro and next year’s World Cup in Qatar represent the last best chance for Belgium’s talented core, its leading edge, to make history.

“We are known now. We are the top team. So you have to behave and train like a top player,” Lukaku says. “We play to win. It’s not like 20 years ago that we would try to aim to get like a draw, or like try to win on the counter. Now the mentality is when we play, you play to win—every game.”

In a way, the old approach Lukaku describes was a lot less complicated then pondering reasonable standards for success or celebrating moral victories. Belgium just wasn’t very good, and not much was expected. There had been a solid run in the late 1970s and early ’80s, when the Red Devils were runner-up at Euro 1980 and a surprising fourth at the ’86 World Cup. The Belgian league enjoyed some time in the sun as well, as Brussels power Anderlecht won the old UEFA Cup and Cup Winners’ Cup a combined three times, and Club Brugge advanced to the 1978 European Cup final.

The subsequent seismic shifts in the soccer landscape, however, left Belgium chasing its increasingly wealthy and influential neighbors by the turn of the century. Its clubs were less relevant, player production slowed and the national team failed to qualify for the 2006 and ’10 World Cups and the ’04, ’08 and ’12 Euros. In the summer of 2007, the Red Devils ranked as low as 71st in the world. That’s not good—the U.S. has never fallen below No. 36.

Lukaku says the seeds of change were planted around 2000, when Belgium cohosted the Euro with the Netherlands and won only one game. The spotlight had brightened so around that time, clubs started to work with the national federation to align on technical, tactical and developmental priorities. Meanwhile, individual teams began coordinating with schools to secure additional practice time for youth players.

“They made a program where you could go to high school but then practice in the morning, go back into class, and then practice with your own team at night. And other teams picked up on it,” Lukaku recalls. “That’s what Anderlecht did for me. I lived in Antwerp until I was 14, and they basically gave us an apartment in Brussels, and we moved and I went to school in Brussels and I would practice twice a day.

“The improvement I made at 14 and then 15 was crazy. I was a totally different player.”

It took some time for the strategies to bear fruit, but there were signs of progress at the 2008 Olympics in Beijing, where a U-23 Belgian side featuring Kompany, Fellaini, Dembélé, Thomas Vermaelen, Kevin Mirallas and Jan Vertonghen won three games and finished fourth. Those players were the ripples that became a wave.

“This starts in a way in 2008,” Martinez says of Belgium’s ascension. “There’s something there that starts a real enjoyment for representing Belgium and playing football.”

The critical second stage in Belgium’s development occurred once that improved generation of players started to earn transfers to big foreign (especially English) clubs. Kompany, who started at Anderlecht, switched from Hamburg to Manchester City right after the Olympics. Vermaelen would move from Ajax Amsterdam to Arsenal, and Vertonghen left Ajax for Tottenham Hotspur. Fellaini went from Standard Liège to Everton to Manchester United. Those players performed well, thus opening the door for their colleagues and boosting other teams’ interest in scouting Belgian athletes. It created a virtuous circle.

In fall 2019, the Royal Belgian Football Association unveiled a new brand and national team crest. The old logo featured a red, yellow and black shield emblazoned with two clunky abbreviations: URBSFA and KBVB. Those were the FA’s initials in French and then Dutch, which are two of Belgium’s three official languages. There are German speakers, as well. Belgium’s identity was that it didn’t really have a single identity. The Dutch-speaking Flemish, mostly in the north, and the French-speaking Walloons, mostly in the south, meet in the middle in Brussels, where lots of people speak lots of languages. Friction can be a benefit when forming a national team—good players collide with good players and everyone gets sharper. It can also create problems, especially where language, ethnicity and heritage are concerned.

So the URBSFA/KBVB decided to switch the focus to solidarity and ambition. The new badge is in English. It reads “ROYAL BELGIAN FA.” The federation and national team Twitter accounts also are in English. At a recent World Cup qualifier in Leuven, the hashtag #COMEONBELGIUM ringed the field. It sends a strong signal. Belgian soccer now speaks the planet’s most influential language. It’s being watched and consumed by the world. It’s transportable. It’s comfortable everywhere. And the country’s internal diversity can become a strength when there’s unity of purpose.

“You can highlight as many differences as you want, as many political barriers as you want,” Martínez says. “But everything comes down to the human respect of each individual. If you want to make it work in a dressing room—and it’s not just in sport—when you get people together, if everyone respects each other and they are prepared to work for each other and fight for the same dream, that’s a unifying way to bring a nation together.”

The Red Devils are so good because Belgian players not only are playing at the biggest clubs abroad, they’re assimilating quickly and then thriving. Only two members of Martínez’s 26-man Euro squad play domestically. There are nine from the Premier League, including superstar playmaker and two-time English PFA player of the year Kevin De Bruyne. Four come from the Bundesliga, two are from Serie A, three from Ligue 1 and three—including Real Madrid goalkeeper Thibaut Courtois and forward Eden Hazard—hail from La Liga. They’ve found homes at the highest level, and they bring that experience, confidence and comfort with pressure back to the national team. They’re able to do so because they were empowered by being raised in a country that trains them to adapt.

“It’s a wonderful thing to see, how sport can bring all that diversity into a very good effect and without a doubt, when you go to school as a young boy or girl and you start learning two or three languages, you see life in a different way,” Martínez explains. “You can adapt. You can respect more different ways of doing things, and in a way that’s a big strength of any Belgian footballer—to be able to go abroad. He will adapt straightaway. He’ll make sure he learns the language, and he will make himself available to what the team needs. I think that’s been very clear for me to identify and see the difference of Belgium as a national team.”

After spending eight seasons in England, Lukaku moved to Inter in the summer of 2019. Getting comfortable in Milan was no problem. Italian is one of his seven languages.

“We’re a multicultural country,” he says. “I still live in Brussels now. My neighbor is Moroccan. The apartment downstairs is an Italian woman. On the left is a Spanish woman. My school had 56 different nationalities. My school was known in Brussels for having the most diverse kids. My parents are Congolese, so I grew up in Congolese culture. Everybody in Belgium speaks two languages from the get-go, and when they show the cartoons on TV, they show it in English but with subtitles in Dutch or French.”

Every day in Belgium is about assimilation and adaption. They’ve been doing it their whole lives. In a sense, there’s nothing more Belgian. So walking into a locker room in Manchester or Madrid and getting comfortable with myriad languages, habits and ethnicities is second nature on the very first day. Football can be the focus. It also strengthens the bonds among Belgium’s players. They feel pride carrying the flag abroad, and in the shared technical and cultural foundation of their development. Belgian players are using the resources of the clubs in the sport’s top leagues to get better abroad and then to sharpen their colleagues at home. They’re weaponizing the Big Five against the Big Five.

“It’s like a club environment,” Lukaku says of the atmosphere around the national team.

“I think it’s as simple as the human quality that these individuals are brought up with in their households in Belgium. A young boy wants to play football, and the moment that he achieves the opportunity to go abroad, to leave Belgium, then they come back like world-class footballers, and I think there’s an element of being well-grounded,” Martínez says. “That’s what’s so enjoyable to work with this generation.”

All the ingredients are there for a run at the Euro. It begins Saturday with the opener against Russia in St. Petersburg, the site of that World Cup semifinal. Belgium is loaded, and the Euro has been kinder to smaller countries than the World Cup. Czechoslovakia, Denmark, Greece and Portugal all have claimed the crown. The Red Devils are better than all of them. But tournaments and narratives and fates can turn on tiny things. The better team hits a post, falls afoul of an unsympathetic referee or suffers an untimely injury, and it could end up with a result that’s not an accurate reflection of its prowess.

In that vein, the fitness and availability of De Bruyne, who suffered facial fractures in the Champions League final, and Hazard, who had a miserable, injury-plagued season in Madrid, could be the deciding factors. They are a reflection of Belgium’s progress. Their performance at an isolated event like the Euro may not be.

Lukaku says he’s convinced that the World Cup loss to France offered a lesson in winning football. Grinding out a victory is O.K.

“Now we know that if we want to get a result, let’s do it the scruffy way. We’re ready,” he says. “That’s something that we know now, and it comes also with the maturity of the players.”

Learning to win at this level, to beat the Frances and Spains of the world, represents a final step that very few teams manage. Certainly, it’s rarer for nations the size of Belgium. To come as far as it has, to be as good as it is, is a victory. It’s the triumph that was celebrated by the masses at Grand Place in 2018. And both Lukaku and Martínez insist that the legacy this generation already has left for younger Belgian players is sealed and priceless. The pride the team has restored among Belgian fans is priceless. It’s been No. 1 for nearly three years, ranked higher than all the former champions. It’s set a new standard and it’s paved the way.

“They are marking an era,” Martínez says.

But that doesn’t slow down time for those doing the marking. It doesn’t alleviate much of the self-imposed pressure on an aging core. Ten members of Belgium’s Euro roster are at least 30. De Bruyne will turn 30 during the competition’s round of 16. They’ve got a couple of big tournaments to go, and for them, the end and the opportunity are coming into focus. It’s all becoming a little bit less gray.

“I think the expectation and ambition go hand in hand, because what the people are expecting from us, that’s what we want. That’s our ambition,” Lukaku says. “We are players that put ourselves under pressure. When you play for the biggest teams in the world, this is normal.

“I think the legacy of the players, of our team, is already set in Belgian history. But if you want to leave a mark in world football, I think then you have to win.”

More Stories From Brian Straus:

• The Acclaim and Blame That Come With Robert Lewandowski’s Name

• Kimmich Is Germany, Bayern’s Combination of Will and Talent

• France Great Thuram Sees MLS’s Black Players for Change as a Template

• USMNT Comes of Age in Epic Nations League Final