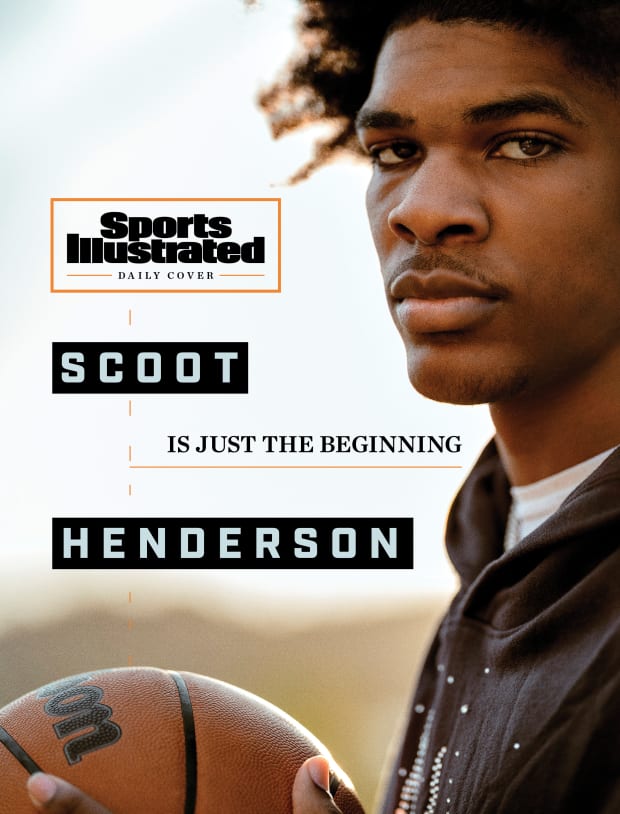

Top prospect Scoot Henderson, who signed a two-year, $1 million dollar deal with the Ignite, is ushering in a new era.

Scoot Henderson has visions of NBA greatness, of All-Star games and MVP trophies and all the glory that comes with it. And he has a chorus of fervent believers cheering him on.

“The best 17-year-old I’ve ever seen,” says Celtics star Jaylen Brown.

“A prodigy,” who plays like “a young Derrick Rose,” says Jason Hart, Scoot’s coach.

“A generational player,” says his trainer, former NBA sharpshooter Chuck Person.

Shaquille O’Neal sends regular texts of encouragement. Russell Westbrook has reached out. Stardom beckons. It’s just going to be a while before the prodigy can meet the hype, at least on an NBA stage.

Brandon Ruffin/Sports Illustrated

The 17-year-old Henderson is only starting his professional journey, as part of the G League Ignite, the NBA’s new talent incubator for players under 19 (i.e., those not yet eligible for the draft). The 6′ 3″, 189-pound guard is a pioneer of sorts—one of the youngest hoop phenoms ever to turn professional in the U.S., and the first to make a two-year commitment to the Ignite. He signed his $1 million contract in May, after his junior year of high school, and he’s projected to be the top point guard in the 2023 draft.

But Scoot’s not thinking about any of that right now. Today, on this late-September afternoon, all he wants in his league-assigned apartment near the Ignite’s training facility in Walnut Creek, Calif., is some decent art. The fully furnished place has drab white walls, neutral-colored furniture and framed watercolors that look like they should be hanging in a dentist’s office. “This is wack,” he says, gesturing at the framed pieces. Henderson favors a bolder look, more inspiring. Some “crazy artwork” and “cool words” on the walls, like he has in his childhood bedroom in Marietta, Ga. Some family photos. Definitely some paint. “I like the color red,” he says. “Might get like a red dresser or something, if they let me have that stuff. But just a whole bunch of posters, really, to make it more soothing. Make it more creative.”

When you’re 17 and 2,500 miles from home—far from your parents and grandparents and the six basketball-playing siblings who helped shape you—you do whatever you can to ease the transition.

So, sure, some posters would be nice, but much better is that CJ, his best friend and the younger of his two older brothers, will arrive in a few days to be his roommate and driver, since Scoot doesn’t have his license. His mother, Crystal, and one of his four sisters, Onyx, are also moving west to manage his daily affairs and live in a house just up the street in the ritzy suburb east of Oakland.

“Just seeing them every day, it’ll make me happier,” Scoot says. “It’ll calm me down.”

It’s a long way from Kell High, where Scoot could be studying for an English test right now instead of figuring out where to shop for groceries. Having dominated high school competition, he knew a year ago that he would leave early. The only question was where to take his talents. College? Top schools like Kansas, Georgia and Auburn were recruiting him. Overseas? He had already turned down a lucrative offer in China as a sophomore. Overtime Elite? The fledgling league, with seed money from Jeff Bezos and Drake, made an offer, too.

Ultimately, Scoot chose the expertise and infrastructure of the Ignite. He will be playing alongside five other high school sensations, all a grade ahead—MarJon Beauchamp, Dyson Daniels, Michael Foster, Jaden Hardy and Fanbo Zeng—as well as a half-dozen teammates in their 20s and 30s who will serve as mentors.

There have never been so many attractive options for basketball prodigies, especially now that college players have the ability to earn endorsement money from their names, images and likenesses. For the first time since the NBA slammed the door shut on high schoolers back in 2006, it’s the players and their families who hold more leverage, says Christian Dawkins, the former player agent who was convicted in an NCAA bribery scandal two years ago and is now the founder and chairman of Par-Lay Sports and Entertainment, the agency working with the Hendersons. Dawkins worked in a broken system where money was shunted under the table to players. Now bidding wars can play out far more in the open, as leagues and universities vie for top prospects.

“It’ll be the most aggressive arms race for talent that the business has seen in a long time,” Dawkins says.

Scoot Henderson is just the beginning.

Noah Graham/NBAE/Getty Images

The aroma of bacon wafts through the kitchen on a pleasant July morning in Marietta, two months before Scoot will move to California. But the sizzling on the stove is quickly drowned out by a crackling debate in the next room over a local seventh-grader’s basketball chops. “He’ll bust your a–!” someone yells, a proclamation met with howls.

Every inch of couch cushion in the modest living room is filled by Hendersons and a few family friends. ESPN is blaring from the television.

“It’s always a sports disagreement in the morning,” says Onyx, 23, who lives a few miles away but, like all her siblings, gravitates back to the family home on a woodsy cul-de-sac. “It’s always shouting. But two seconds later, it’s like, ‘O.K., what are we eating?’ And then after things settle down a little bit . . . we probably go to the gym.”

The gym is Next Play 360°, which everyone in the family calls their second home. Crystal, a health-care administrator, and Chris, a coach and trainer, acquired the space, with its two courts, in 2018, fulfilling a lifelong dream of Chris’s. He’d grown up in difficult circumstances, wishing he had access to this type of haven. They launched a series of camps and tournaments for kids, along with a STEM lab. Says Crystal, “We just want to continue to help them realize they can do anything that they want in this world and then open up their eyes to STEM.”

In this family, basketball really is life. Three Henderson sisters played Division I basketball: Diamond, 29, at Syracuse, and Onyx and China, 26, at Cal State–Fullerton. CJ, 20, played at Kell High until he suffered a knee injury. Their youngest sister, 16-year-old Crystal, who goes by Moochie, is a point guard and one of the top-ranked preps in Georgia. The oldest brother, Jade, 28, preferred football but can hold his own in family pickup games. Chris has coached them all since they were toddlers dunking on plastic hoops and continues to train them at Next Play 360°. Crystal runs the gym. And all of the Hendersons can be found there nearly every day, Scoot sometimes until 2 a.m. before his move west.

Those in Scoot’s orbit describe him the same way: serious, reserved, hyperfocused, mature beyond his years but a kid at heart, a sensitive soul. When his sisters went away to college, Scoot would call them almost daily to check in. He’s also the Henderson most likely to scream through a horror movie.

On the court, though, is a different story. “He might start off kind of cool,” says Diamond, “but then the monster just comes out and he can’t contain it. It’s like the Hulk. Sweetest guy, he’s so humble, and then he gets on the court and you just see this green monster. And then he’s flying in the air, dunking it as hard as he can, hanging on the rim.”

Nearly all the Henderson siblings say they grew up as Kobe Bryant fans, including Scoot, who has a purple No. 24 Lakers jersey hanging in his bedroom. Scoot seems to channel his hoops hero when he talks about his own work ethic: “The grind is just special. You can’t enjoy the end success. You got to enjoy the grind, so you can get that success.”

He was born Sterling Henderson, but just about everyone has called him either Scoot or Scoota since he was a toddler. The roots of that moniker are the subject of family debate. His siblings say it had to do with his scooting across the floor on his rear, but Crystal insists, “It’s just a nickname.”

As the second-youngest of the Henderson Seven (as Crystal calls them), Scoot took his basketball lumps early, playing against his older siblings. “All seven of us would be out there to one, two o’clock in the morning,” says Diamond, “going at it, crying, arguing, fighting. My dad would have to referee us a lot of times just so we didn’t kill each other.”

The indoor activities were just as intense, whether the siblings were playing Uno or Monopoly or just racing to the door. There are various scuff marks along the walls and moldings where the Hendersons have “dunked” on one another, using a real ball but an imaginary hoop. (Crystal, needless to say, was not amused.)

In a family of chatty souls, Scoot is the quietest. But as the quiet types often do, he was soaking up every lesson and adopting the best pieces of his siblings’ games. He meticulously lists them: China’s jump shot, Diamond’s fadeaway, CJ’s hesitation move, Onyx’s footwork. He has even picked up some shooting technique from Moochie, who Scoot says is the family’s finest long-distance sniper.

The best passer? “Me,” Scoot says softly, sounding more matter-of-fact than boastful. When it’s suggested he will eventually rank No. 1 at all of the above, he says, “Hopefully, yes.”

And so when it was time to make the most consequential decision of his life, Scoot once again drew on the collective wisdom of his family. “All nine of us,” Crystal says.

Brandon Ruffin/Sports Illustrated

It’s a fabulous time to be a teenager with sick handles and major hops—the best since the NBA instituted a rule 15 years ago that players must be at least 19 years old and a year removed from high school to be draft-eligible. The NBA’s minor league, then known as the D-League, which did allow 18-year-olds, was in its infancy and paying very little. A smattering of U.S. players went abroad to mixed results. The NCAA held a virtual monopoly on the market for elite talent.

But in 2019, the G League started offering “select” contracts, worth $125,000, to a handful of high school stars. The next year the NBA launched the Ignite, attracting stars like shooting guard Jalen Green and small forward Jonathan Kuminga with a far bigger haul: reportedly around $500,000 for each. Two months after Scoot struck his two-year deal with the Ignite, a 16-year-old big man from Oakland, Jalen Lewis, signed with Overtime Elite, reportedly for more than $1 million. The Atlanta-based OTE is offering players a minimum of $100,000 per season to play for one of their three squads of teenagers.

By next summer a third option should be available: the Professional Collegiate League, which plans to start with four teams spread across the Mid-Atlantic and will pay $50,000 to $200,000 per season, plus scholarships to attend local schools. Add in professional leagues in China, Australia and Europe, and you get what Dawkins calls “a perfect storm.”

“It’s a battle royal on a bigger scale now because now you have everybody on a global level coming after teenagers,” says Dawkins. “The price will just continue to rise, which I think is a good thing for the players.”

Dawkins will advise the Hendersons on marketing and business matters but, because of his conviction—he served six months in federal prison—he cannot represent players as an agent. His firm employs other certified agents who are handling Scoot’s basketball contracts. “He helped us understand the space a lot more, and what is to come,” Crystal says. “A lot of people don’t want you to know. They don’t want to empower you.”

If there were any doubts about the Ignite’s viability for launching NBA careers, they were silenced in July, when Green went No. 2 to the Rockets and Kuminga went to the Warriors five picks later. That proof of concept will surely encourage other young phenoms, like Scoot, to follow their path, drawn by the advantages of competing against teams with seasoned players in their 20s and 30s, working with NBA coaches and learning NBA sets and focusing on a basketball career without having to juggle schoolwork.

Scouts attending Ignite games last season told Chad Ford, who covers the draft via Substack after years as an ESPN guru, that they found it easier to evaluate Green and Kuminga than the college prospects in the 2021 draft class. “So if you shine” in the G League, says Ford, “I think the takeaway is that’s a safer bet in the draft than someone who shines in the NCAA.”

It will be 19 months before Scoot can test that theory, and, of course, much depends on how he’ll perform over the next two seasons. It’s difficult to say how far this will all go—how big the contracts will get and how many teens will be signing them. But a future in which the top of the NBA draft board is dominated by ignite, ote and pcl, instead of kentucky, duke and gonzaga has all but arrived. Scoot Henderson represents the next stage of player empowerment—the prodigy who plots his own path, free of NCAA strictures, and stakes his claim before ever stepping foot in the NBA.

Brandon Ruffin/Sports Illustrated

Scoot’s decision to leave the comforts of high school, turn pro and move across the continent unfolded the way many things do in the Henderson household. “We throw out the options as a family,” Crystal says, “and then we do the pros and cons. And it’s a lot of yelling and screaming and fussing and whatever.”

The deliberations went on for months, culminating last spring in a family meeting in the STEM lab at Next Play 360°, where Scoot made his decision over a takeout feast from Infusion Crab. The discussion lasted just 10 minutes.

Scoot knew exactly what he wanted and never wavered. The Ignite offered better competition than the NCAA. The G League offered more stability and a longer track record than OTE. “It’s one step closer to my main goal, getting to the NBA,” he explains. “That’s really it.”

He had nothing left to prove in high school; as a junior he averaged 32 points, seven rebounds and six assists and was the state’s Class 6A player of the year. Scoot’s closest friends, including CJ, had graduated in 2019. Sure, he would miss out on things like homecoming and the senior prom, but none of that mattered much to him. So last fall Scoot doubled his academic workload in order to graduate a year early. He left with a 3.5 GPA (the G League requires a high school diploma).

More than a dozen big-time college programs put offers on the table. The allure of the NCAA is still potent: March Madness, national television exposure, the chance to be the BMOC. But that, too, held little appeal for Scoot, who will play in relative anonymity for the next two years.

The Hendersons also knew well the pitfalls of the NCAA: Diamond, China and Onyx all sustained career-altering knee injuries in college and felt as though they were treated as disposable commodities. “My daughters got hurt,” Crystal says. “And there was nothing.”

All three got their degrees, but as the family saw it, there wasn’t sufficient compensation for their physical sacrifice. “The way the Hendersons think, not just with the NCAA, but just in general, might be the reason why [our] alliance was able to come together smoothly,” Dawkins says. “I think we’re both mavericks or risk-takers to a certain extent and have a strong viewpoint.”

The NCAA policy change that will allow athletes to profit from their names, images and likenesses came about six weeks after Scoot signed with the Ignite. But it wouldn’t have made a difference, he says. And the seven-figure contract? Scoot allows it was a factor, but so were the online college courses and life-skills programs the Ignite provide: “That’s why I don’t like when people just say, You just went for the money.”

As Diamond puts it, “In the next few years, you can be a millionaire—why wouldn’t you go hard now, to be able to live the rest of your life the way you want to live and create generational wealth for yourself, as well as the family?”

Brandon Ruffin/Sports Illustrated

The road to stardom begins in a bland apartment complex overlooking a gas station, across from a Target, in an unfamiliar city. Scoot has been training with the Ignite for about a week, adjusting to his strange new reality. Onyx has settled in up the road, but CJ and Crystal have not yet arrived. It’s quiet here.

“I miss my family,” Scoot says, “and my mom’s cooking”—especially her macaroni and cheese, though Scoot’s low-carb diet might rule that out, anyway.

The Hendersons are navigating the same mix of excitement for Scoot and separation anxiety, with some living in Walnut Creek and the rest back in Marietta. But they’ll all be making regular treks to the Bay Area and to as many games as possible, both home and road. (The team does not have an arena of its own, so will play its “home” games at Mandalay Bay’s arena in Las Vegas.)

When Scoot initially settled in, the whole family traveled for a one-week reunion at the new house. China, the family’s resident fashion consultant and interior designer, planned to help Scoot personalize his new space. But at the moment, it’s just Scoot and his empty apartment with the bad art. On the plus side, there’s no one else hogging the Wi-Fi, so his PS5 works seamlessly running NBA 2K.

The transition on the court is going well enough. Though he missed the Ignite’s first three regular season games with a broken rib, Scoot returned to the lineup on Wednesday, registering 8 points, 6 rebounds and 3 assists in 16 minutes. He’d already made a quick impression in camp on his teammates and on his coach, Hart, who played in the NBA for nine years, including two stints with the Spurs during the Tim Duncan era.

“When he trains, you don’t know he’s 17,” Hart says. “It’s almost like on some Kobe mindset, focused, driven.”

In practice, Scoot already looks the part of an NBA player—lean and chiseled and explosive. Person, his trainer, says he’s seen Scoot pick up the ball off one dribble after crossing midcourt and fly in for the dunk. His jumper is a work in progress, though Person had Scoot shooting (and converting) from 30 feet. “He’s going to be a Russell Westbrook with range,” says Person.

The Celtics’ Brown, another Marietta product, has become a friend and mentor. He has also scrimmaged against Scoot, coming away with this conclusion: “No back-down, no quit. Relentless. Which I love.”

The Bay Area might prove hazardous for the average teenager with time on his hands and money to blow. But Scoot seems wholly uninterested in anything that doesn’t involve a basketball. He spends his free time either on the PS5 or reading and just finished a self-help book called The Four Agreements. His favorite lesson? “Be impeccable with your word.”

Scoot almost recoils at getting a driver’s license, that cherished rite of passage, saying with a joyful cackle, “I want to stay young forever!” Anyway, if he decides to explore his new surroundings, he says, “I’ll take the bus.”

With the season underway, a new normalcy will follow. He’ll have CJ, Crystal and Onyx nearby, and the rest of the Henderson Seven will descend on every Ignite game possible, making their raucous presence felt. Whatever Scoot becomes over these next two seasons, he will carry an entire family’s hopes and dreams with him.

“It’s going to be a challenge,” Crystal says of this strange two-year interlude. “But I think we’re close enough to make it work. This is an opportunity of a lifetime. This is generationally changing. The story line that can come from this is well worth just grinding it out.”

More Daily Cover stories:

• ‘Honey, You’re Not in Waco Anymore’

• ‘The Coach Has No Power Anymore’

• From No. 1 Gonzaga to No. 358 Maryland Eastern Shore