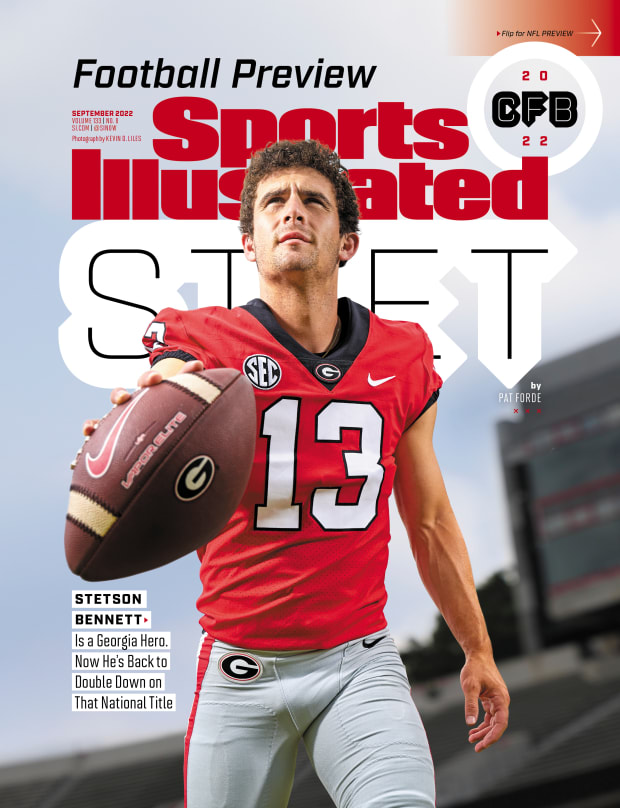

The lightweight walk-on improbably led the Bulldogs to the national title last season. Now, the Georgia quarterback is back for an encore.

Stetson Bennett is late. Rock-star late. It’s more than an hour past our scheduled meeting time at the Georgia football facility, and venerable associate athletic director Claude Felton is driving us to a sub-division of townhomes on the edge of Athens in search of the Bulldogs’ improbable star quarterback.

Felton, who has worked at his alma mater since before Herschel Walker enrolled in 1980, is flustered. He’s adjusting to the odd audible that has been called. Bennett is supposed to be dropping off his truck at a teammate’s home to have it detailed, and the plan is to meet him there to squeeze in some extra interview time while driving back to the facility.

Except Bennett isn’t at the teammate’s house, either. We pull into a parking spot and wait some more, awkward small talk interspersed with the checking of phones. Eighty minutes after the original meeting time, just when we’re about to give up, Bennett comes through. Georgia fans can likely relate.

Bennett pulls up in his black Ford F-150 Raptor pickup. He climbs into the back seat of Felton’s car and apologizes profusely. “I have a date tonight,” he says, explaining why he wants his truck fancied up. Bennett doesn’t go into detail, but when asked whether he’s the most eligible bachelor in Athens, he laughs sheepishly and says, “I guess so, yeah.”

Here’s how you can get Sports Illustrated’s Football Preview today!

Stetson Fleming Bennett IV becoming a college heartthrob and timeless hero to the masses who follow Georgia football still takes some getting used to, for him and his family back home in Blackshear, Ga., four hours south of Athens. “Anonymity is gone,” says his mom, Denise. “He’s still Stet, still my boy. I’m still reminding him to get his oil changed. But some things have changed. I’m very thankful he’s 24 and not 18.”

Stet is a star quarterback now, evolving into the position and the persona, a disorienting reality after years of being doubted and considered disposable. In the annals of underdog athletic triumphs, Bennett’s 2021 season ranks right up there. Once the small-fry walk-on who walked off after one season went to junior college and returned only to be serially demoted, he became the Offensive MVP of the College Football Playoff championship game after earning the same honor in the Orange Bowl semifinal blowout against Michigan. He also was fourth in the nation in pass efficiency.

And now he’s back for the encore, a sixth-year senior ready for a final season in the role he’d wanted since he was a toddler. It’s been a hell of a victory lap since he helped deliver Georgia’s first national championship in 41 years last January at Lucas Oil Stadium: getting the celebratory first sip from a family friend’s bottle of 23-year-old Pappy Van Winkle; flying as a celebrity guest inside a jet with the Blue Angels; being asked for selfies outside the Sistine Chapel in Rome and in front of Michelangelo’s David in Florence during a May study-abroad trip; and receiving name, image and likeness opportunities commensurate with being the biggest man on campus.

Now, it’s time to get back to football and answer the next question: Without a historically great defense backing him, can Stetson Bennett come through again?

David E. Klutho/Sports Illustrated

Stetson Bennett wasn’t just born to be a Bulldog; he was nearly born in Sanford Stadium, where his parents had season tickets. Stetson III remembers a very pregnant Denise thinking she was going into labor during a Georgia-Kentucky game on Oct. 25, 1997. Three days later, Stetson IV arrived.

By age 3, Stetson IV was telling his dad he wanted to play quarterback at Georgia. That was all the motivation Stetson III needed to become a youth league coach. He bought an acre lot next to his pharmacy and turned it into a football field, organizing a team and feeding the boys peanut butter and jelly sandwiches before putting them through a Bible devotional, study hall, a CrossFit workout and, finally, practice. Even by south Georgia standards, this was intense.

“I felt like I owed football,” says Stetson III, whose father, Buddy, was a football coach. “Football educated my daddy, and he had five kids and we’re all educated. I felt like football broke the cycle for our family.”

An outstanding athlete, Stet excelled throwing and running (and playing baseball). By high school, he was a star in the making at relatively small Pierce County High. He put up big numbers, earning his nickname, The Mailman, for always delivering. He led his school to three straight state playoff berths, but his small stature (generously listed now at 5’11”) kept major college recruiters away.

An acknowledged “unrealistic coach and daddy,” Stetson III at one point set off on a two-week driving trip through Mississippi, Louisiana, Texas and Arkansas to market his son as high-level college quarterback material. He had an iPad loaded with Stet’s game videos, stopping at several FBS programs and trying to talk his way in. Often, he got no further than a graduate assistant who was willing to look at the video for a brief time. Sometimes, he didn’t get that far.

“It was tough,” Stetson III says. “Because football’s always been fair. We had a saying, ‘It ain’t easy, but it’s fair.’ Then all of a sudden you feel like it wasn’t fair. But what are you going to do, sit there and [wallow] in it? Get up and go back to work.”

At summer camps before his senior year, Stet put on performances that the family should have warranted more attention. “He would be competing against all the people who had the cameras around them, and was destroying them,” Denise says. “That was my Holy Cow moment. Like, he’s good.”

Still, Stet was rated a two-star recruit and received just one FBS scholarship offer, from Middle Tennessee. The best he could get from his dream school was a chance to walk on. In the spring of 2017, he took it and began the humbling experience. His assigned jersey—No. 22—was an insult in and of itself, more appropriate for a defensive back than a quarterback. He got half a locker, No. 122 A, sharing the space with No. 122 B, fellow walk-on QB John Seter. Their general rule: Whoever got to the locker first could claim the space for the day.

But instead of being intimidated or discouraged by his place in the hierarchy, the cocksure QB was motivated by it. Assigned to the scout team, Bennett set out to frustrate the first-team defense in practice and catch the eye of coach Kirby Smart by executing the opponent’s plays to perfection.

“The most blunt way to say it, he had a ‘f— you’ attitude,” says Seter, who is now playing at Limestone University in Gaffney, S.C., but remains close friends with Bennett. “And it was awesome.”

But scout-team glory doesn’t always translate to playing time, especially when Jake Fromm led the Bulldogs to a spot in the CFP title game. Then there was incoming mega-recruit Justin Fields. With his path to competing for the starting job blocked, Stet transferred to Jones County Junior College in Ellisville, Miss. “I wasn’t interested in being a frat kid on the football team,” he says. “I wanted to play ball.”

After a stellar season there, he was ready to sign with Louisiana-Lafayette when Georgia called on signing day to offer a scholarship. Fields had transferred to Ohio State, and the job backing up Fromm was wide open. The coaches asked for an immediate decision. The FU QB told them they could wait a spell and consulted his parents. Dad was all in. Mom was worried about her son again being buried on the depth chart. Still, he knew he would regret not giving himself every opportunity to try again. He went back to Athens.

Stet played well in spot relief in 2019, and his assumption that Fromm would turn pro after that season proved correct. The opportunity to win the starting job was right there in front of him in ’20. Then Georgia went heavy in the transfer market, taking in starters Jamie Newman from Wake Forest and JT Daniels from USC. Freshman D’Wan Mathis also was given a shot. Stetson calls the situation a “fiasco” that caused him to consider leaving again. But Newman left before the season began, Daniels was slowly recovering from a knee injury, and Mathis was in over his head. Bennett grabbed the starting spot after the opener and played with a verve and daring that at times were unsupported by his physical talent. When he and Mathis were ineffective in a bad loss against rival Florida, Georgia turned to Daniels and finished 8–2 on the year. It was assumed the Bulldogs would turn to him for ’21, as well.

That demotion didn’t last long. Daniels struggled with injuries early last year, and, by Week 4, Bennett had taken over the starting job, complementing an all-time great defense as Georgia rolled through the regular season 12–0. The only question was whether he could make the necessary plays to win when the defense was not dominant.

The test came against a rare underdog Alabama team in the SEC title game. The Bulldogs’ defense played its worst game of the season, and Bennett made a couple of critical errors in a stunning rout that raised all the old fears in the fan base, with much of the college football punditocracy wondering whether a switch back to Daniels was Georgia’s best move. Stet’s parents couldn’t help but notice how quickly the Bennett bandwagon emptied again.

“If I’m speaking from the flesh, it sucks,” Denise says. “If I’m speaking from where I need to be, it’s a learning curve. It would be harder for someone who was a five-star recruit who was lauded and didn’t become a starter. … Do I say things in response in my mirror at night? Yes, I do. Loud and proud. Then I get over it.”

The playoff became the ultimate validation for Bennett and the Bulldogs. They destroyed Michigan 34–11 in the Orange Bowl, scoring the first five times they had the ball, with Stet throwing for 313 yards and three touchdowns. That earned a rematch with Georgia’s demon, Alabama, with everything on the line—including, fair or not, Stetson Bennett’s legacy. “No matter what, it’s never going to be normal again,” Denise thought. “Win or lose.”

Kevin D. Liles/Sports Illustrated

Just before halftime in Lucas Oil Stadium, a miserably nervous Denise Bennett had to excuse herself. She left the Georgia parent section and retreated to a concourse bathroom. “I had to get my head right,” she says.

The Bulldogs were trailing 9–6, offensive frustration mounting, pressure intensifying. Wearing her son’s jersey number, Denise was heartened by words of encouragement from fellow Georgia fans. Sitting in the concourse and regrouping, many of them came up to tell her, “Your boy’s got this.”

And in the second half, he did. But not without facing one more trial that left the world ready to give up on him again.

Holding a 13–12 lead in the fourth quarter, Bennett was flushed by Alabama linebacker Christian Harris and threw the ball away, arm going forward at the Georgia 10-yard line and ball landing at the 16, where Crimson Tide defensive back Brian Branch casually grabbed it before stepping out of bounds. Somehow, the play was ruled a fumble, and Alabama had red zone field position for the go-ahead score. It took four plays to retake the lead.

At that point, the Georgia fan meltdown was in full effect. But on the sideline, Stet was simply ready for another chance to redeem himself. The former shortstop compared it to fielding a line drive as opposed to a slow roller—everything happened so fast, all he could do was react and get back on the field. There was no time to ponder the stakes and attendant pressure.

“If you’re thinking, Oh my goodness, if I don’t throw this ball perfect then it’s over, you’re screwed,” Bennett says. “If you’re thinking of the magnitude of every play on every play? Forget it, man.”

When Georgia returned to the field, offensive coordinator Todd Monken did Bennett a favor by opening up the playbook. “Just ripping it the whole drive,” Stetson says. “That was big.” Monken called five straight passing plays, resulting in three completions, an Alabama interference penalty and a sack. On second-and-18 from the Bama 40, Bennett went deep to Adonai Mitchell for the go-ahead score.

After stopping the Tide, Georgia pounded the ball downfield to a third-and-1 at the Alabama 15. That’s when Bennett found tight end Brock Bowers for a 15-yard touchdown that produced an eight-point lead and put Georgia on the brink of a title. Bennett had done his job on the two drives since the disastrous fumble, completing all four passes for 83 yards and two touchdowns. No Georgia quarterback had ever performed better in such a huge moment than the walk-on turned walk-off turned serially demoted Stetson Bennett IV.

Kevin D. Liles/Sports Illustrated

Still, it wasn’t over until freshman cornerback Kelee Ringo rose up and snared a Bryce Young pass, then returned it 79 yards to clinch the title. That’s when Bennett started sobbing on the sideline. He finally realized how much he’d been carrying and let it go.

“I didn’t let myself think about what would happen if we won or lost,” Bennett says. “If you do, you get overwhelmed—like, it’s a big deal. We have the wants and desires of millions of Georgia fans on us; that’s a pretty heavy load. I literally felt all that slide off my shoulders and I started crying.”

A second catharsis came when Stetsons III and IV saw each other postgame.

“A lot of tears,” Stetson III says. “Literally, this is what we worked for. We wanted to win a championship for the University of Georgia. Who ever gets the opportunity to be what he said he wanted to be at 3 years old?”

The celebration, however, had just begun. After finishing media obligations at the stadium, the Bulldogs returned to the Westin nearby. It was 3 a.m. and the lobby was still bedlam, four decades of pent-up enthusiasm being released. At that point, Patrick Jones and a small coterie of friends grabbed Stetson and edged off into a more private alcove.

Jones is a South Georgia homeboy and friend of the Bennett family. “Avid, rabid—whatever you want to call it, I’m that kind of Georgia fan,” Jones says. He attended the last national title game in New Orleans on Jan. 1, 1981, as a teenager, and the bitter overtime loss against Alabama in the CFP title game in January 2018. He absolutely was going to be in Indy, and he absolutely was going to bring a very expensive bottle with him.

Jones owned a chain of 180 convenience stores called Flash Foods before selling them, and along the way he became friends with a lot of people in the liquor business. Several years ago, he came in possession of a 23-year-old bottle of Pappy Van Winkle bourbon, which at present can be bought in select locations for somewhere in the neighborhood of $6,000. The bottle was never opened after the loss to Bama four years earlier; Jones believed there would be another opportunity.

After the rout of Michigan, he texted Stet and told him he was bringing the Pappy to Indy and wanted him to take the first drink after Georgia beat Bama. Stetson’s reply text: It would be an honor. Unfortunately, though, I have a rule for myself that I don’t plan postgame festivities. I have to do the duty that lies nearest to me, which means taking care of business Monday. I’m going to have to forget about this until after the game.

Business taken care of in thrilling fashion, it was time to break the seal. Bennett took the first swig straight from the bottle with cellphones recording the moment that would end up going viral. It was passed around the group until the Pappy ran dry.

Jones is putting the bottle and an empty box of Cuban cigars from that night in a shadow box display in his home. It’s thrilling enough that the Bulldogs won another title, but doing it with an underdog local boy playing quarterback? That’s worth breaking out the good stuff. “Everyone here feels tons of pride in Stetson,” Jones says. “He’s had a lot of naysayers over the years, but he is determined beyond words.”

Back at the Georgia facility, the improbable rock-star quarterback shows his command in the team’s offensive meeting. Looking at big-screen diagrams of the plays the offense will run through in a few minutes on the practice field, he rattles off the reads and keys for multiple positions. On the field, he chatters nonstop with staffers or fellow quarterbacks. When it’s time to run sprints at the end of the workout, he showcases his conditioning. He moves around the building with an understated but discernible swagger. This is his domain.

Disarmingly candid and quick with a quip, he is more comfortable in his dream role than he has ever been. With the NFL not frothing over an undersized quarterback with ordinary arm strength, the decision to stay in school and reap the NIL benefits of being a local hero was an easy one. And, for once, Bennett enters the season without having to look over his shoulder. There is no doubt who will lead Georgia into the opener.

“I’ve got the greatest gig in the world,” he says. “It’s going to be different, in a good way.”

Austin McAfee/Icon Sportswire/Getty Images

Bennett’s preparations have included poring over film from every 2021 game—twice—looking for areas to improve. He has sharpened his footwork, which he described as “a little flippant” last season. He has been vigilant on the practice field about his upper-body mechanics as well, constantly checking his arm positioning and torso torque.

Something else that is different: There likely will be a greater need for Bennett to be a centerpiece of the team. Last season Georgia’s formula was to build a lead and let its defense, which allowed an NCAA-stingiest 10.2 points per game, suffocate opponents. It wasn’t a constant necessity for Bennett to make big plays, though he is certainly capable. He was third nationally in yards per attempt at 10.0, and Georgia ranked in the top 10 with 30 passing plays of 30 yards or more, even though Bennett was just 79th in attempts (287).

But with eight of the record 15 players drafted off last year’s team coming from the defense, five of whom were taken in the first round, Georgia will need more of Bennett to have a shot at a repeat national title. It also is replacing its top two rushers and No. 1 deep threat. “We’re on top of the world, but we’re going to see the world here in a few weeks,” he says. “Better be ready.”

In his football element, Bennett shows some characteristics of the historical figure he gravitated to during that European trip, the “Unearthing the Past” program led by Georgia professor of classics Mario Erasmo. A history buff, Bennett studied everything related to Julius Caesar, the most famous of Roman emperors and generals. “He was fascinated by Julius Caesar,” Erasmo says. “Like Caesar, Stetson plays to win.”

Yet Bennett is the counterpoint to Caesar’s ancient warning to conquering Roman heroes. According to legend, an enslaved person was assigned to whisper in the ear of returning generals, Sic transit gloria mundi—all glory is fleeting. For Stetson Bennett IV, the hero no one saw coming, Georgia Bulldogs glory is forever.

More College Football Coverage:

• Pat Forde’s Preseason Top 25 Ranking

• Examining Barnhart’s Message to Calipari, Stoops

• Nick Saban Prepping Alabama For Its Next Evolution

• How the ESPN–Big Ten Split Impacts College Sports