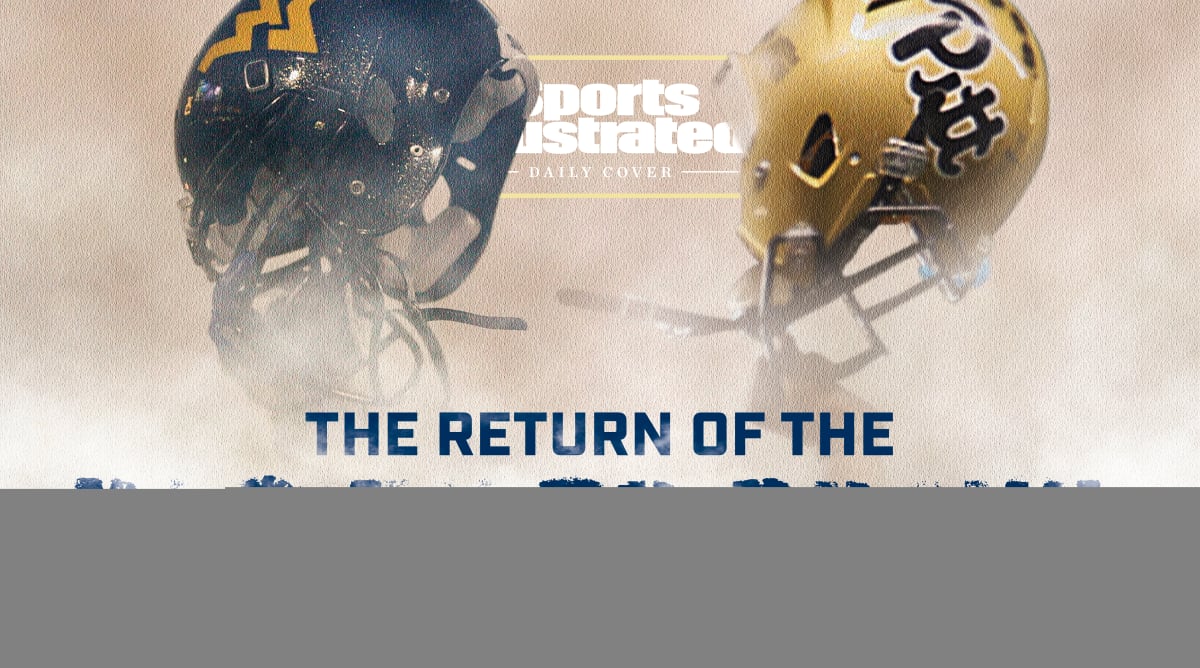

On the 15th anniversary of the Brawl’s most stunning chapter, one of college football’s greatest rivalries returns as a reminder of the sport’s rich tradition and, for some, agonizing history.

Long before he evolved into a wrestling and broadcasting star, even before he burst onto the scene as a prized NFL punter, Pat McAfee drove aimlessly across the American terrain.

It has been 15 years since, and he recalls very little about the drive and says he has not spoken publicly about it. He remembers brushing away the broken beer bottles in his driveway that West Virginia fans hurled at his Jeep Wrangler amid the violent aftermath of Dec. 1 2007, the worst night of his life when his reliable foot partially cost the Mountaineers a chance at a national championship. His car was vandalized, his yard destroyed, his life threatened.

So, McAfee hopped into his Jeep and did what so many West Virginia fans requested of him: He disappeared.

“My life changed immediately that day. It was a terrible f—— night, to be honest with you,” McAfee says. “It was like something out of a movie. I just drove. I got all the way to Virginia through Maryland. I was gone for a couple days. I drove, parked, slept and kept driving. I didn’t know where I was. I didn’t know where I was headed. I didn’t know what was coming next.

“And I didn’t know if I wanted to live anymore.”

Outsiders might think it is silly that one game could mean so much to a person, or that it could forever fracture a relationship between a coach, Rich Rodriguez, and his one true love, West Virginia. But that one game—Pitt 13, West Virginia 9—left as many scars as any game in the history of college football. For some, the wounds are as fresh as they were in 2007, an infamous date for an entire fan base and state left heartbroken by its archrival.

Those involved say outsiders don’t understand the situation, the stakes and the series.

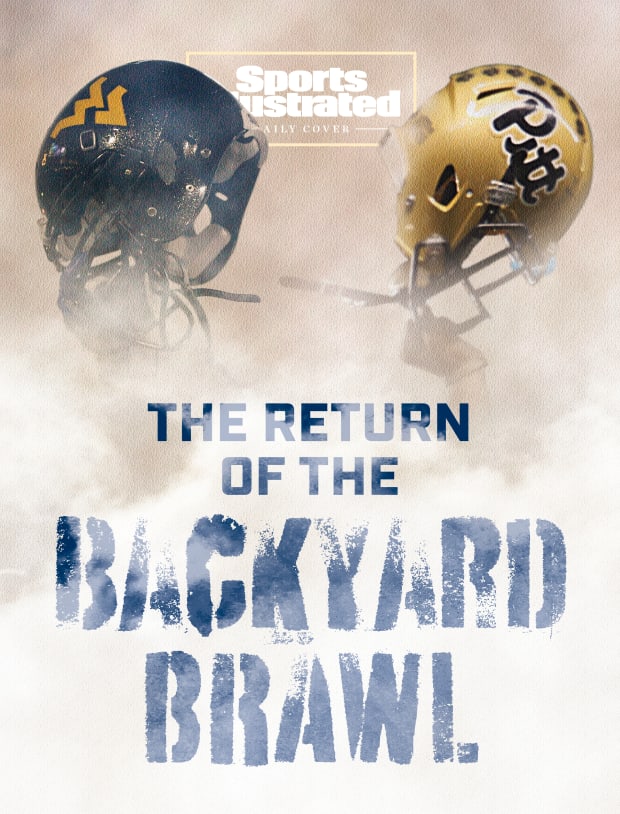

On the 15th anniversary of the Backyard Brawl’s most stunning chapter, one of college football’s greatest rivalries returns Thursday after an 11-year hiatus. Pitt vs. West Virginia. City vs. country. Steel vs. coal.

“Pitt and West Virginia, there is a hate there,” former Pitt defensive coordinator Paul Rhoads says.

There have been 104 Backyard Brawls, and although Pitt has won 61 of them, West Virginia has considerably tightened the series, holding a 21-19-2 edge since 1970.

The schools, separated by about 75 miles, are demographically dissimilar—Pittsburgh’s metro area (2.3 million) is bigger than the entire population of West Virginia (1.8 million).

Before its latest hiatus, the Brawl nearly died in the 1940s, when the series stopped for three years because West Virginia, in dire financial straits, owed Pitt $20,000 for guaranteed games played in Morgantown the previous decade. (Thankfully, the issue was resolved.) The series has literally produced brawls —in ’76, when Pittsburgh’s Tony Dorsett was ejected for sparking a fight, and in ’70, when the Bobby Bowden–led Mountaineers squandered a 35–8 halftime lead and forced the coach to keep his players in the locker room for an extra hour to avoid an angry mob of fans.

The Brawl also has created heroes—men named Jock (Sutherland), Gibby (Welch) and Bimbo (Cecconi). It has even featured duels between brothers—in 1965, Paul Martha’s 46-yard touchdown run lifted the Panthers to a victory against brother Richie’s Mountaineers.

“Like most big rivalries, there are awesome stereotypes,” says Oliver Luck, a former Mountaineers quarterback and athletic director. “It is ‘sophisticated city folk’ of Pittsburgh against ‘the hillbillies’ of West Virginia.”

Pitt fans famously say the only route to Morgantown is by swinging along tree vines. The Mountaineers counter with a three-word chant that often erupts at various WVU sporting events, no matter if the two teams are playing. Eat s—, Pitt!

No single chapter of the Brawl featured bigger heroes and battle wounds than “13–9.” Thursday night’s resurrection of this century-old series is a reminder of college football’s rich tradition, elegant pageantry and, for some, agonizing history. The Mountaineers enter the game, as they have for years now, holding a special distinction—no major college football program has won more games in its history without having claimed a national championship. Fifteen years ago, on a cold night in Morgantown, the Mountaineers missed their latest chance at destiny.

“You make a play that makes a difference in this game, you can become a legend,” Dave Wannstedt, the former NFL coach who played and coached at Pitt, says. “People will talk about you forever.”

Damian Strohmeyer/Sports Illustrated

Mike Patrick, a former NFL and college football broadcaster, is two years into retirement. He lives in Virginia, but he has not forgotten his roots. He’s a West Virginia boy, born in the mountain town of Clarksburg and raised to despise one school.

“I hated Pitt before I knew what Pitt was,” he says with a laugh.

He attended his first Backyard Brawl in 1959 at age 15. Nearly 50 years later, in 2007, Patrick got assigned to call his first and only Brawl game as ESPN’s lead play-by-play announcer. He was overcome with excitement. What’s better, he thought, than broadcasting his home state school’s biggest moment to the world?

“It was going to be the best game I’ve ever done. Personally, it turned out to be the worst,” he says. “I waited my whole life, my whole career for it. It’s a good thing I didn’t have a permit to carry a gun. I don’t know that I would have made it out of the stadium that night.”

The 2007 West Virginia Mountaineers team was a group of “misfits,” McAfee says. They outsprinted everyone with swagger and athleticism, and benefited from the schematic genius of their coach.

Rodriguez, a former West Virginia defensive back and homegrown West Virginian then in his seventh year as coach, puzzled defenses by utilizing running back Steve Slaton and quarterback Pat White in a zone-read spread concept that is now part of virtually every offensive playbook. Outside of a Week 5 hiccup against a ranked South Florida team, the Mountaineers were near-perfect with a 10–1 record and ranked No. 2 in the nation behind the country’s most electric offense (the unit averaged 41.6 points a game).

The 2007 college football season, dubbed the Year of the Upset, was one of the wildest in the history of the sport. Top 5 teams lost to unranked opponents a record 13 times, and programs ranked No. 2 in the AP poll lost seven times in the final nine weeks of the regular season. As teams faltered, the Mountaineers kept creeping up the polls and entered the final week of the season in position to reach the BCS championship game against, in all likelihood, Ohio State.

One team—an unranked, 4–7 squad from Pittsburgh—stood in their way. “It was the last hurdle between us and immortality,” says Jed Drenning, West Virginia’s radio sideline reporter.

The Mountaineers were 28-point favorites and had posted a combined 90 points and 1,133 yards against Pitt the previous two seasons. The Panthers were starting a true freshman quarterback, had yet to win on the road and lost to Rutgers, UConn and Navy.

Confidence was so high in Morgantown, the father of WVU fullback Owen Schmitt ordered 100 celebratory T-shirts before the game. The BCS title game that year was in New Orleans, so the shirts featured a court jester with the words “Bayou Bound!”

Scott McKillop, Pitt’s standout linebacker in 2007, doesn’t blame anyone for doubting the Panthers. “We sucked,” he says. “If we play 100 times, we probably only beat them one time.”

As Pitt arrived at the stadium, West Virginia fans pelted the team bus with beer bottles and rocks. “It sounded like hail,” recalls Pat Bostick, the rookie quarterback who started that night.

Bostick didn’t get much sleep the night before. It wasn’t nerves, but rather an infection so bad he says blood oozed from his ear. Things got worse. In the third quarter, Bostick scored Pitt’s only touchdown on a one-yard sneak. He flipped into the end zone, smashed into a defender and was punched from under his chin.

“I saw stars,” he says. “I was absolutely concussed, but I wasn’t coming out of that game.”

Pitt’s defensive pressure, meanwhile, knocked White out of the game with five minutes left in the second quarter, produced a crucial sack-fumble on his backup in the fourth and held Slaton to a season-low 11 yards, roughly 80 below his average. Panthers running back LeSean McCoy led the night with 38 carries for 148 yards, and Pitt’s defense blitzed virtually every down using the same rover back zero play with variations that were designed to clog every running gap and get into the backfield to harass White and Slaton.

White missed roughly two quarters with a dislocated thumb on his nonthrowing hand, but returned for the final two drives of the game, both of which ended on failed fourth downs in Pitt territory.

David Bergman/Sports Illustrated

“You feel helpless,” says White, now an offensive assistant for the Los Angeles Chargers. “Thinking back on it, I probably should have said, ‘Forget that thumb.’”

White’s injury came nearly two decades after Lou Holtz and No. 1 Notre Dame beat Don Nehlen’s third-ranked Mountaineers in the Fiesta Bowl to win the 1988 national championship. In that game, WVU’s star quarterback, Major Harris, separated his shoulder on the very first play.

“It is one tear-inducing moment after another,” Patrick says.

The 2007 outcome affected LSU more than any other team, paving its way to the title game. Late that Saturday night, the score reached the Tigers as they were returning to Louisiana after winning the SEC championship in Atlanta. As the team plane descended into Baton Rouge, the pilot announced the score. Players and coaches erupted with such force that the jet dangerously dipped.

“We had a party at however many thousand feet up we were,” recalls Michael Bonnette, the team’s longtime sports information director. “We broke several FAA violations.”

For weeks, Wannstedt received cigars and thank-you letters from LSU fans. The Tigers ultimately beat the Buckeyes, 38–24, delivering coach Les Miles his only national championship.

White has never watched a replay of the game and won’t unless tied down and his eyes are taped open, he says. His memories are somewhat lost. “You know how people go through traumatic stuff and they forget about things?” he asks.

Many from that West Virginia team still live in the state. Schmitt, the fullback whose father had those shirts made, is a UPS supervisor living in Dawson. Williams works at a poultry and beef farm in Morefield.

“We just have to live with the biggest loss in our history. That’s all,” Schmitt says sarcastically. “It’s not like I never think, ‘I wonder what would have happened had we won the natty?’ Lives would have changed.”

Drenning attended the game with a friend who was so distraught that the man decided, in the middle of the night after the game, to walk home. It was 12 miles away. “He was in a dark place. He’s told me about the things that went through his mind that night,” Drenning says. “These are the kind of stories you hear from West Virginians.”

High above the stadium, Patrick, who painstakingly remained impartial during the broadcast, waited for everyone to leave the press box before he slipped into a side room, closed the door and screamed at the top of his lungs. “I got to give myself credit,” he says. “I held it in.”

For McAfee, Dec. 1, 2007, was a debilitating event. The team’s place-kicker and punter entered that game having made 10 consecutive field goals. On West Virginia’s first drive, he hooked a 20-yard kick left. On its third drive, he pushed a 32-yarder right. McAfee, a fan favorite, took pride in being a Mountaineer and was known for celebrating victories with casual fans across Morgantown. Each August at their home, he and linebacker Reed Williams hosted a barbecue event for the team and fans.

Everyone knew where they lived.

“We were sitting around our kitchen table speechlessly looking at one another, and our house was getting bombarded with bottles all night long. You’d hear the thud of the bottle and glass shatter,” Williams says. “You’d see the remnants of beer and liquor bottles. The rest of the semester, Pat was receiving death threats. The guy got torn down.”

David Bergman/Sports Illustrated

Rich Rodriguez lives with regrets. First, he acknowledges using a too-conservative game plan on the night of Dec. 1, 2007. And secondly: “It was a mistake to go to Michigan,” he says. Two weeks after the Brawl loss, on the night of Dec. 15, a day after interviewing for the job in Ann Arbor and a day before accepting it, Rodriguez held a heated conversation with West Virginia school president Mike Garrison. He was searching for reasons to stay. He got none.

Garrison reportedly told him, “We’ve done all we can; take it or leave it.”

“I was like, ‘Gee whiz,’” the coach says now. “Most people don’t know that. I don’t think I’ve told anyone that before.”

Garrison lasted just 14 months as WVU’s president after his hiring was announced in April 2007. His office was consumed with controversies over favoritism before the faculty voted to call for his resignation, which he gave in June 2008.

Rodriguez, meanwhile, says he has never spoken publicly about why he left his home state and alma mater. He claims to have three times caught university administrators misappropriating donations meant for football. Those donations, for facilities improvements and the like, were made, in part, because Rodriguez turned down the Alabama coaching job a season before.

And many have wondered whether those events would have played out differently if the Dec. 1, 2007, Brawl ended in West Virginia’s favor.

“It’s the biggest ‘what if’ in our history. No doubt about it,” says John Antonik, the director of content for West Virginia athletics and author of a book detailing the Pitt–West Virginia feud. “I’ve had people ask me this as recently as just a month ago: Did Rich Rod throw that game?”

When asked about it, Rodriguez scowls with his response. No, he says, he did not purposely lose what was the most important game—and self-described “biggest nightmare”—of his professional career, one that led to him vomiting in the locker room afterward. He’s offended, maybe even hurt, that so many West Virginia fans still believe his departure for Michigan two weeks after that game was connected to his team’s performance that night.

“It pisses me off. That is total bulls—. Bulls—,” says Rodriguez, now coach at FCS Jacksonville State. “Those conversations didn’t take place until a week after that. Anybody who says that doesn’t know what the hell they are talking about.”

Says Drenning: “Rich wanted to do things for the program, and he felt resistance from the administration. Ever since I knew the guy, West Virginia was his dream job. I think he had a vision of what we could be, and others didn’t think we could be that.”

Rodriguez’s exit did benefit one player, at least.

“I don’t know if it took the target off my back and put it on him,” says McAfee, “but I do remember, like people telling me, like actually telling me around campus, ‘I hated you for it all until Rich went to Michigan.’ I’m like, ‘O.K., thanks. I appreciate that!’”

The two men were bonded forever over missed field goals and messy exits. They went without communicating for more than 10 years before McAfee was on a broadcast team for one of Rodriguez’s games in 2019 while he coordinated the Ole Miss offense. They spoke then, exchanged numbers and developed a relationship over texts.

Still, the pain remains for McAfee. He has returned to campus only once, for a 2015 halftime ceremony to honor the ’05 group that beat Georgia in the Sugar Bowl and launched the best three-year stretch in Mountaineers history—three conference titles, three top-10 final rankings and 33 victories. McAfee flew in that morning, drove directly to the stadium and didn’t stay for the end of the game.

“It’s tough. I let down a lot of people. Do you want to pop back in and go to a place where you literally made every human there miserable and upset? That’s not my vibes,” he says. “I let down basically everybody I care about—my family, myself, my teammates, my coaches, everybody who’s invested time in me at West Virginia.”

After the 2007 game, ensconced in his home, he made the mistake of opening his Facebook page.

“I had a bunch of people I thought I was friends with sending me DMs to never show my face, kill myself or that, if they could, they’d try to kill me,” he says. “I cried for probably seven or eight hours straight. I remember listening to what people were screaming into the house. It was at that moment I was like, ‘I should disappear probably.’”

Williams has attempted to convince his former roommate to return to campus again. It’s not like McAfee hates West Virginia. On the set of his radio show, he proudly has his West Virginia jersey on display. He roots for the Mountaineers. He wants them to beat Pitt “by 1,000,” he says.

“He’s loved here,” says Williams. “I don’t think he feels that reciprocated. It’s been hard for him to reopen his heart.”

As for Rodriguez, many West Virginians loathed the coach for that two-week stretch in December 2007 and forget about the 60 games he won over seven years. Patrick jokes there are likely armed guards on the West Virginia border anticipating his return, and when asked whether time will heal such wounds, the former broadcaster quips, “We’ll all be dead by then.”

Rodriguez returns to the state, and Morgantown, every couple of years to visit his brother and 83-year-old mother. To this day, though, he’s never returned to campus, visited the facilities or been invited back for a game. He says it bothers him. “I hope we can go back, all of us at some point.”

He will forever consider West Virginia home, but knows there are scars. They follow him everywhere, even to tiny Jacksonville, Ala. Upon taking over the Jacksonville State program this spring, he had his new players complete an information sheet. One of the questions: Tell me something interesting about yourself.

An answer from one player, a West Virginia native: My dad took a picture of you and set it on fire when you left West Virginia.

Jared Wickerham/Getty Images

The heroes of the 2007 Brawl game rolled into Pittsburgh on the team bus while singing John Denver’s “Take Me Home, Country Roads.” Players sang, off and on, since the game had ended. Their voices could even be heard in the background during Rodriguez’s postgame news conference, booming from the other side of the wall.

Country roads, take me home

To the place I belong

West Virginia, mountain mama

Take me home, country roads

At 3 a.m., the Panthers returned to a city alive. Bars stayed open late, welcoming players and coaches for beer and pizza. Couches burned on the street.

“There were no rules,” McKillop says. “We could have done about anything, and no one would have cared.”

McKillop, the Pitt linebacker who famously stopped Slaton on a fourth-down run in the fourth quarter, is notoriously outspoken about the feud between the two programs. He once told a reporter for a published story of West Virginia, “I f—— hate the university and I f—— hate the state.”

Years later, he now lives in the state, married into a family of Mountaineers with two children born in the state, and West Virginia University is one of his most prominent clients for his medical device sales job. “They remember my last name,” he says. “It took a little extra to win them over.”

The impacts of the upset were far reaching. West Virginia held a big recruiting weekend for the Brawl game, with at least a dozen prospects watching from the Mountaineers sideline. Some chose between the two schools. Pitt signed roughly eight of those players. Some even left their WVU official visit to join Pitt in its postgame celebration. That December, the Panthers sent prospects Christmas cards with the short message: “13–9.”

Pitt fans often refer to that game by the score and find any way to insert it into conversations or photos. In May, Pitt coach Pat Narduzzi posted a message on Twitter that counted down the days until the season opener with a photo of Pitt players charging onto the field.

You can guess which two helmet numbers were most prominently featured.

But why, after all these years and great games, did the series go dormant for more than a decade? The answer centers on the sport’s usual suspect—conference realignment, a money-grabbing endeavor that has consumed college sports and, to some, has shattered the game’s history and tradition.

In 2013, the ACC finished off the Big East by taking Syracuse and Pitt and leaving West Virginia scrambling. “The ACC denied us,” recalls Luck, AD at West Virginia from ’10 to ’14. “The SEC was a maybe, but it depended on Missouri’s decision. We may have had an opportunity [to join the SEC] if Missouri would not have gone.”

Missouri’s move in 2012 opened a spot for the Mountaineers in the Big 12 and disrupted the Brawl’s annual date. In one of his first acts as athletic director in ’15, Shane Lyons opened communication with Pitt to restart the series. They will play eight times over the next 11 years.

With their closest conference game 800 miles away, the Mountaineers have revived other old rivalries with their neighbors, such as Penn State, Virginia Tech and Maryland. In a world where such games are disappearing because of realignment and guaranteed-win games, Lyons is bucking the trend. West Virginia has played or will play 11 Power 5 games from 2018 to ’24, excluding the COVID-19-impacted ’20 season.

“Why aren’t we all playing 11 Power 5 games?” Lyons asks. “Are we doing what’s right for college football? The TV deals are lucrative and important to all of us in operating our departments, but you are breaking up these geographical rivalries.”

The rivalry’s revival has fans buzzing. The average ticket price on the secondary market is at more than $200, ranking among the highest-priced games of the season. Lyons knows of West Virginia fans who bought Pitt season tickets just to secure entry to the Brawl, he says. The game sold out weeks ago, and Pitt sold another 200-plus standing-room-only tickets within five minutes of opening sales.

Most of the players competing Thursday night were in elementary school when the two teams last tangled on that cold night in Morgantown, and very few people who were part of the programs in 2007 remain. Bostick is the color analyst for Pitt’s radio broadcast, and each team employs an assistant coach from the ’07 staffs—Jeff Casteel is a defensive analyst who was West Virginia’s defensive coordinator for that game; and Charlie Partridge, then Pitt’s special teams coordinator, is now a defensive line coach.

McAfee, meanwhile, has evolved into the biggest celebrity from that game. Several people have invited him to Thursday night’s game. He says he will unlikely attend but will be watching, rooting on his Mountaineers, 15 years after that long, lonely drive with a destination he’s still in search of.

“Hopefully, [coach] Neal Brown will be able to win a natty so I can get this weight off of me.”

Watch college football live with fuboTV: Start a free trial today!

More College Football Coverage: