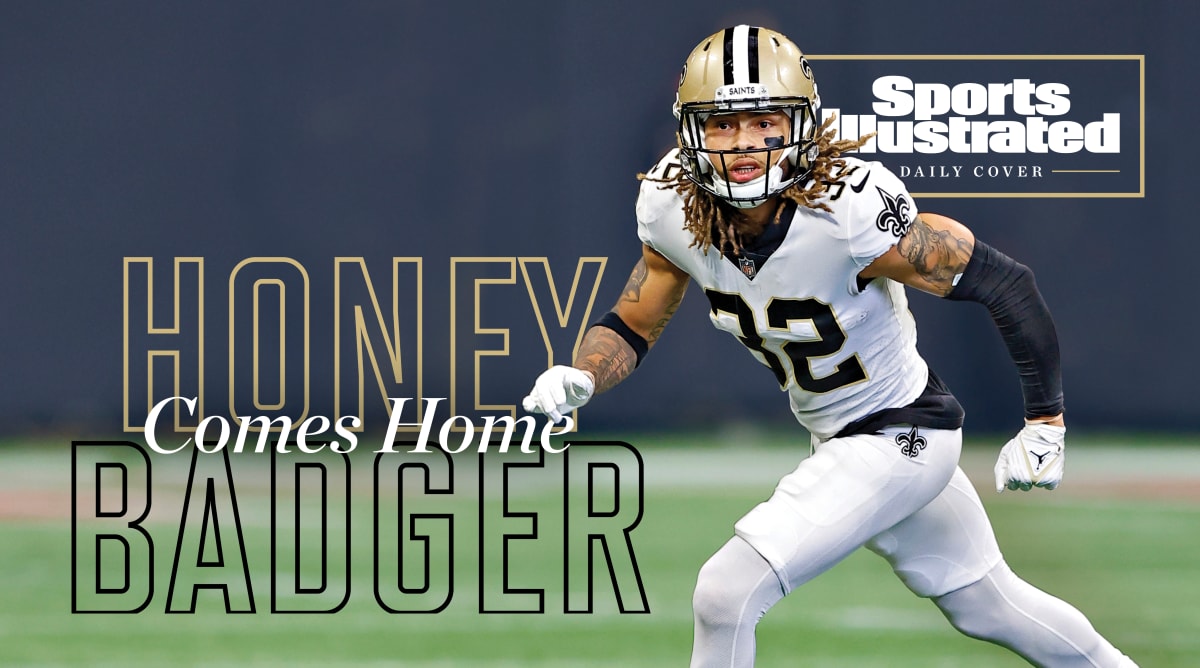

Tyrann Mathieu’s journey to his hometown team has been long and difficult. A feel-good story? It’s not that simple.

Classes at Northshore High School are in session, but no one bothers the NFL veteran strolling from the parking lot toward the football field. That’s part of the balance he’s seeking, what’s necessary for the task ahead. He could drive to his hometown of New Orleans in under 40 minutes, and yet, he’s here, in Slidell, La., and not there, intentionally, just far enough away.

It’s a random July weekday, as Tyrann Mathieu carries a bright yellow backpack adorned with cartoon stickers through the overwhelming heat. Consider the bag a parental survival pack: wet wipes, green sippy cup, baseball gloves, candy. Anything to ensure a successful upcoming season for the NFL safety who roves on the job and from one gig to the next.

Tyrann Jr., age 8, and Mila, 2, trail behind, eyeing the sugar like tigers stalking prey. “What’s your name?” Mila asks anyone in earshot. She points to her father and announces, “This guy, his name is Daddy.” Giggling, she adds, “He’s here now.”

Todd Kirkland/Getty Images

Mathieu is here. Is back. In every possible sense, after signing with the Saints. Back training like before the LSU superstar days, basic and brutal and intentionally Rocky-esque. Back motivated, even more than normal. And back, well, home, which might sound perfect but isn’t. Not exactly.

He loves New Orleans, loves the people, culture and vibe. The locals love him back. They crashed a website that sells custom Saints jerseys, swarmed him in public and urged him to run for mayor or city council. But there’s a part of him that’s wary, too. Or vigilant, at least. His best friend, Terry Lucas, likes to consider them both survivors. They spent their teens surrounded by poverty, gun violence, hurricanes, drug use, gangs, destruction, self-destruction, abandonment and death—they’re fortified and armored. They’re also guarded.

Mathieu isn’t returning to survive, though. He’s coming back to impact his hometown far beyond the football field. It’s heavy, because it’s him, it’s New Orleans, and it’s complicated. Hence a homecoming that’s unlike other homecomings, that’s bigger, more fraught and potentially transformative. The idea thrills him until it terrifies him, and he flips back and forth, trying to make sense of what’s possible and what’s not, where he fits and what he can let go.

He sometimes joked about this possibility with friends, family, even longtime Saints coach Sean Payton. Truthfully, though, Mathieu always believed that when he did return, it would be as an assistant coach at LSU. But play? At home? Come on. No way. That’s the stuff of fairy tales.

Soon rain will fall and not in drops but in waves. Thunder will crackle in the distance. Mathieu will remove his tank top and continue sprinting with resistance bands attached to his waist. “I never thought I’d be able to come back still wearing my superhero cape,” he says.

Maybe this is a fairytale after all. Enigma to adversary to hero. Maybe, he thinks, it could be perfect. Storybook. Roll credits. The End.

The thought is forceful but fleeting, like the thunderclaps in the distance. Look closely. Notice the ink on his right leg, row after row of nearly identical crosses that explain why his relationship with his hometown is as much thorns as flowers.

The tattoos represent his torture and his torment, the friends and family members Mathieu lost during childhood alone. He added all 22 at once, over two sessions, one for each cross and one for the initials denoting each individual who died.

Fairy tale? Please. Tyrann Mathieu has a graveyard on his leg.

The ink hints at why this homecoming isn’t as charmed as it might seem. And why, for Mathieu, the feelings tied to his return are not dissimilar to the resistance bands now straining around his waist. He knows it won’t be easy. He expects many twists.

The downpour turns the parking lot into a concrete lake. Workout finished, Mathieu carefully navigates the deluge, opens the high school’s football office, changes into a gold T-shirt and settles into a black folding chair. He’s ready, now, to tell the full story of his homecoming, painful as it might be.

To understand what it means—for Mathieu and his hometown, after all their shared and volatile history—he starts in the one place he never wanted to leave.

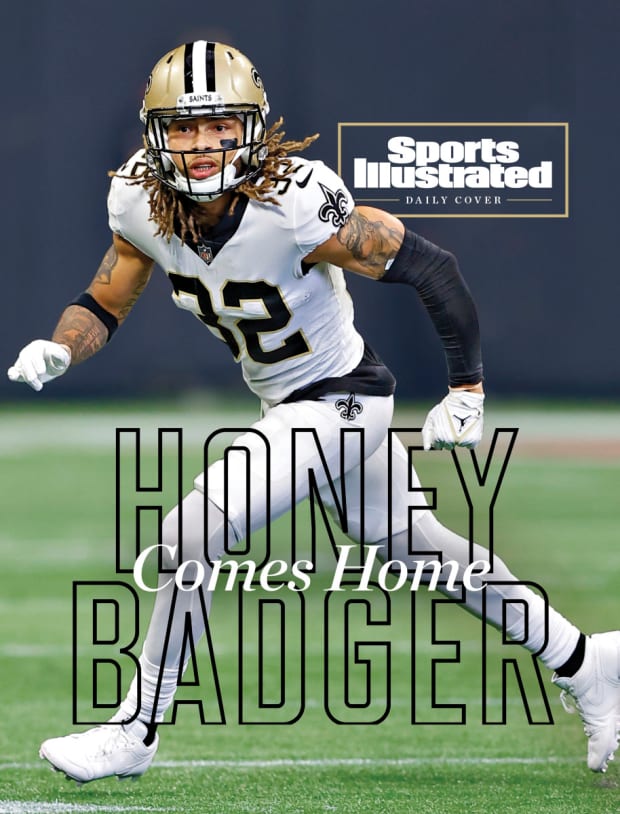

When the Chiefs signed Mathieu in 2019, everyone from general manager Brett Veach to coach Andy Reid to defensive coordinator Steve Spagnuolo heralded his arrival. All said they planned to rebuild a shaky and aging defense in his ethos. They wanted the fiery leader with the versatile skill set, a safety who could defend the run and cover the league’s best slot wideouts and tight ends.

Mathieu promised to deliver, on all of it, but he also wanted something else: to end the doubts that circled him, that made his career a mixture of accolades and storm clouds, regardless of how often he played, where or how well. Some of this uncertainty was internal, or internalized, as Mathieu’s social media feeds filled with his angst. He fired back at critics. Or he invented them, adding to a stream of perceived slights.

He told friends he wanted to retire like Ed Reed and Troy Polamalu, a Hall of Fame defensive backs synonymous with one particular place and its football team’s success. “He was hoping Kansas City would be that for him,” says Scott Savage, Mathieu’s mentor and pastor.

“Like, forever,” Mathieu says.

Simon Bruty/Sports Illustrated

He simply needed to deliver, and delivering amid doubt marked something of a specialty. He did, once more. His 13 interceptions tied for fifth-most in the NFL over the past three seasons. He missed one game. He made two Pro Bowls, was twice named first-team All-Pro, helped lead the Chiefs to their first championship game in half a century, won a Super Bowl (LIV) and went to another (LV).

Last year Mathieu nabbed team MVP honors, and the Chiefs nominated him for the Walter Payton Man of the Year award. But despite a stretch he considered ideal, he couldn’t shake an ominous feeling.

It started right before training camp last season, when Mathieu says he met briefly with Veach for an informal chat over how he fit into the team’s future. This, too, was more complicated than it seemed. Mathieu loved Kansas City. The Chiefs loved him right back. But the Chiefs had salary cap constraints—the escalators in Patrick Mahomes’s mega-deal and potential, massive extensions for left tackle Orlando Brown Jr. and wideout Tyreek Hill, plus a lower-than-anticipated overall salary cap due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Mathieu recalls Veach pointing out that had made a lot of money playing football—at that point, roughly $58 million—and had earned the right to test the free-agent market. The conversation was setting the table for a future contract; Veach was likely signaling that he didn’t have the kind of cash Mathieu might command at the top of the market—but it also seemed to be a sign that the GM wanted to make a deal. If the safety wanted to return, the Chiefs would welcome it, but at the right price, especially as the team looked to get younger on defense.

Mathieu may not have picked up on the subtle message. If he did, he didn’t convey his understanding to the team. Instead, he says he reminded Veach to remember who his agent was. Tom Condon didn’t do team-friendly deals.

Though the meeting wasn’t contentious, both left without clarity. Veach, per the team’s protocol, would not discuss an extension during the season. The player and GM didn’t have a significant conversation for months, engaging in only brief interactions (daps at practice, hugs after big wins). Mathieu came to view the silence as a different kind of signal. Maybe Kansas City wanted to move on. This, like so much in his life, was grounded in perception.

The Chiefs won their opener, lost four of their next six games, then ripped off eight consecutive victories to climb back into the Super Bowl picture. Looking back, Mathieu can pinpoint a single play that embodied the team’s uneven season: Raiders, mid-November, covering speedy DeSean Jackson on a deep post. He dove for an interception. The ball slipped through his grasp. Jackson caught it. Jackson fumbled. Mathieu recovered. “Up and down,” he sighs. “Up and down …”

Did he wallow through the season, self-doubt screaming louder than any external noise? He doesn’t think so. Though he’s not sure. But he has some thoughts …

Mathieu speaks deliberately. He doesn’t want to sound defensive or bitter; he was not and is not. But he does believe that team chemistry was harmed by so much success, a not-uncommon corollary connecting many near-dynasties that never quite formed. Mathieu says K.C. was “too conservative” at times (AFC championship game) and “too comfortable” (overall). His emphasis for most of the regular season centered on the collective mindset. “Getting guys to believe we got to climb a mountain again,” he says. “Not believing that, you know, our house is already on the top.”

Without naming anyone specifically, he also points to ego as a catalyst for unraveling—relative, of course, to the Chiefs’ potential, the multiple titles almost seized. “A lot of people want to be the reason that we win, and they want to take the credit,” he says.

Still, with the GM silent and the locker room at least somewhat fractured, Mathieu showed up every day and presented himself as a solution. Sure, he sometimes slipped on social media, responding to anonymous critics with egg avatars.

Otherwise, he never let his growing angst, the internal uncertainty of 2021, bleed into his football. His statistics showed little, if any, drop off: three picks, three fumbles recovered (tied for the NFL lead), one touchdown and 76 tackles, along with the highest coverage rating (88.1) and lowest missed tackles percentage (9.5%) of his K.C. tenure.

He served as a team captain—and one coach cited him as the defensive catalyst who saved them. He mentioned that to a coach before a playoff game that he and Veach had hardly talked that season, and the coach went to the GM’s office and told Veach he needed to check in with his star safety. Mathieu says Veach found him in the locker room. “What’s up, man?” he started. “I’m not avoiding you!” Perhaps the saga had all been a giant misunderstanding. Mathieu still isn’t sure.

He left the epic, overtime playoff victory over Buffalo with a concussion, sidelined after only one series. He watched NFL history not from the sideline, but from his own couch, with his fiancé, Sydni Russell. He returned the next week for the conference championship against the Bengals, and, after the overtime loss, he tried to summon positivity. He tried lying to himself; of course he would be back. But he also told Sydni he had played his final game for Kansas City.

“What about ‘forever?’ ” she asked.

Darkness descended. He grew depressed. In the months after the season ended, Mathieu says he never heard from the Chiefs. Hadn’t he just won team MVP? Hadn’t they just come one bad half and blown lead short of a third-consecutive Super Bowl appearance? “I had given them everything,” he says.

Even then, he thought, maybe they’d make him an offer. Eventually. He wished. While waiting, he refused to engage with other teams, trying to manifest some way to remain in Kansas City. But, from his perspective, Veach’s offseason decisions left no room for interpretation. The Chiefs signed free-agent safety Justin Reid on the first day of the league’s legal tampering window in March.

Reid’s contract—three years, $20 million guaranteed, worth up to $31.5 million—stung. He won’t pretend he took the news well, and he means the actual news, because he found out, same as everyone else, when reports leaked. “I was really offended,” he says.

If offered those exact parameters, Mathieu says he would have signed without hesitation. It’s possible Mathieu’s playing style would have fit alongside Reid, that it wasn’t a zero-sum exercise on the safety market. And it seemed the Chiefs still wanted him back. The safety market was mostly stagnant; Veach remained in contact with Mathieu’s representatives, and defensive coordinator Steve Spagnuolo kept in touch with the safety himself. But Mathieu didn’t see how a return could happen.

With Mathieu still unsigned, Kansas City selected a safety (Bryan Cook, Cincinnati) in the second round of the NFL draft in April. After striking a deal with the Saints, Mathieu says Veach sent a long text message, filled with compliments like, “we’ll never be able to replace you.” Thank you, Mathieu tapped back, along with other praise for their time together. At that point, he didn’t seem upset. Maybe he wasn’t. Maybe he was more wounded and confused. He couldn’t stay where he wanted, and this, for a man abandoned on his very first day on earth, felt more personal than perhaps it was.

He would always hold Kansas City in his heart—“a huge testament,” says Dr. Suneil Jain, Mathieu’s mind/body coach, “to who he has become.” In time, he believes the wounds his departure opened will close.

The NFL calendar moved forward, same as always, and Mathieu knew he needed to do far more than move on. He needed to turn inward once more, no matter how much it hurt. Saying it was one thing. But doing it? Again?

During one of the darkest weeks this spring, Mathieu needed help. No matter how hard he tried, he couldn’t move on. Couldn’t will calm. Couldn’t force inner peace. So he sat down with his fiancé in their living room in Kansas City. It no longer felt like home. Had a player of his caliber—lauded for intangibles, impactful on the field, his admittedly checkered past growing more distant every year—ever played for four teams in their first 10 seasons?

Is it me?

That look. Wow. He knew Sydni was trying to help, and he wasn’t angry. However intended, though, it still hit like a slap across his face. Did he see pity? Protective instinct? He’s not sure. But when she said, “Maybe God wants to sprinkle your greatness around,” he rolled his eyes, mumbled “whatever,” and continued searching.

What remained of his pro football career depended on finding the right answer to that question. Was it him? The existential hunt led Mathieu to a familiar place: the gap between how the wider world saw him and how he saw himself.

Hadn’t it always been like that? Slipped to the third round of the 2013 draft? Excelled in Arizona, until injuries made him expendable after 2017? Taken a one-year deal with Houston the next season and transformed the culture of the Texans locker room, only to be cast back into free agency? Then the drama in K.C.?

Mathieu couldn’t shape how executives might label him, couldn’t stand outside of facilities with a sign announcing his selection to the Pro Football Hall of Fame’s all-decade team (2010s). He could control his preparation, state his impact through statistics and what he put on film, and string together year after year without off-field incidents. But even then, he couldn’t stay in Kansas City unless the Chiefs wanted him to stay in Kansas City.

He tried a trick from therapy: attempted to understand their reasoning. He did turn 30 in May. He does have a documented injury history—although it’s distant, the bulk of his missed games from 2016 or earlier. Perhaps they considered his sideline theatrics more distracting than motivational. Or didn’t like the Twitter clapbacks. Shrug. “I can’t look back anymore,” he says. “I gotta take my life for what it is.”

Jeff Kravitz/FilmMagic/Getty Images

He hated moving, packing up in one place and ingratiating somewhere else. Always. Again. But none of these tags had negatively impacted his performance. They were just that, tags. The feelings they unearthed—abandonment, guilt; that he was unworthy, unloved—were also just feelings. None would sink him into a forced retirement. Not unless he let them.

Where, then, would he go? Mathieu hadn’t thought about next steps in any real depth. But an idea started percolating, a seed that seemed too unrealistic to plant outside of his own mind. What if his new home was also his first home?

No way, he thought. Too cinematic.

Tyrann Mathieu is New Orleans. New Orleans is Tyrann Mathieu. That’s not hyperbole. Both are parties of one, sui generis, unlike anywhere or anyone else. Both are flawed and misunderstood, fairly maligned and charming in their imperfections. James Carville, the political consultant, author and Louisianian, describes that spirit as a “deepening of everything”—the depth rooted in history, mythology, tradition, sorrow and, above all, a sense of place.

Carville likes to tell strangers that any measure typically used to identify a list of most livable American cities—days of sunshine, hospitals, traffic congestion, cost of living, threat of extreme weather—probably won’t apply to New Orleans. “But there’s no other place that has such an identifiable way of life,” he argues. “Everybody eats red beans. Everybody goes to the Saints games. I mean, that’s the draw: connection, overcoming.”

Mathieu buys that summary. But how he came to view New Orleans evolved as he did. It’s difficult to describe the inherent duality with nuance, and not because he’s hiding or too scarred. Outsiders can’t get it, not really, because they don’t understand how the best and worst of New Orleans can exist in the same place, at the same time, on the same street. So they box him into familiar narratives, using what makes sense to them to make sense of him.

He reconsiders. Perhaps Kansas City wasn’t the ideal starting point to truly understand the complexity baked into his homecoming. It’s complicated began well before the season of silence. It really started on the day he was born.

His biological father, Darrin Hayes, was locked up in prison for robbery on May 13, 1992. Hayes killed a man the same day he was released and would soon be convicted of second-degree murder. Mathieu’s mother abandoned him before then, leaving Tyrann on his grandparents’ doorstep. He lived in poverty. He lost relatives and friends to gun violence, as his graveyard of tattoos reminds him. He was adopted by an aunt and uncle after his grandpa died. One of his best friends was gunned down while sitting on a stoop in the Fifth Ward in 2012.

“Being from New Orleans, it’s like, everybody had that story,” Mathieu says. “People put that label on you. If I showed any sign of anger, sadness, or grief, they immediately project my childhood onto it. It’s not that simple …” He trails off, mind spinning back in time. The past explains the present. The present explains the past.

New Orleans almost destroyed him, right? He thought that for so long. Sometimes he forgot about the older brother, Tyrone, who aced his classes and showed Tyrann he could love and cry and not be less than, a punk. He pushed good memories away, down to subterranean depths. Like every Sunday in the fall, when the Fifth Ward gathered for gumbo and Saints games. Or the night in February 2010, when a franchise once mocked as the Aints, paper bags over heads no longer, won the Super Bowl. He sped down to the French Quarter to join the jubilation and saw what he did not yet feel: hope.

At St. Augustine, the majority-Black Catholic high school he attended, Mathieu met lessons of grace, acceptance and empowerment with indifference. He clung to confrontation, his only means of escape. He played in one all-star game, USA vs. The World, that could symbolize a life summary. His team vs. The World.

John Biever/Sports Illustrated

At LSU, he grabbed picks, returned kicks and floored national audiences as a true freshman in 2010. He embraced the Honey Badger nickname, because he, too, hunted with strength, ferocity and toughness. He didn’t grasp that actual honey badgers, because of those same traits, sometimes challenged prey they had no chance of killing. What made them so unusual helped and hindered their chances of survival.

Mathieu netted national defensive player of the year honors in 2011. But by ’12, after too many failed drug tests and confrontations, he was no longer welcome in Baton Rouge. When he bid goodbye, he never planned on coming back beyond short, unannounced visits. When he did pop in, he brought security with him, fearful, he says, that his profile made him a target for robbery, extortion, or the kind of jealousy that might lead old friends to “try” him. “I know the streets,” he says. “You can’t not be aware of that. Like, that’s real. That’s a possibility.”

Thus began a sort of trial separation. “For him to go back, there was inherent risk,” Savage says. “It’s tiring. He can be hard on the outside, going toe-to-toe with Tom Brady in the Super Bowl. But there’s a soft center to him. He does want to be liked, accepted, affirmed for who he is.”

While necessary, the distancing went over poorly. Mathieu sometimes felt villainized, even when he tried to help. Like in 2016, when Saints legend Will Smith was killed, right there on Magazine Street in the Lower Garden District. Mathieu went on the Rich Eisen Show and spoke emotionally, saying he didn’t feel safe spending more than 48 hours back home, because “people” knew where to find him, wanted altercations and reached for guns over any sign, however minor, of “disrespect.” He meant what he said. But the interpretation—that he hated his hometown, believing himself better, above the struggle—was twisted beyond recognition, until his calling Smith’s killer a “coward” birthed a deluge of death threats.

He needed only to glance back at that right leg. Would he become a cross rather than the one who carried them?

In April, unemployed and deep in a “funk” he couldn’t shake, Mathieu decided to fly home. He planned to visit his oldest son, 9-year-old Noah, who lives in New Orleans, along with other relatives and favorite haunts.

For months, he had told his agents to treat his latest round of free agency the same as after Arizona cut him. He wanted a one-year, prove-it deal, another way to bet on the only person he truly trusted—himself. Teams called, but Mathieu hardly engaged beyond the Eagles. Their general manager, Howie Roseman, went full courtship, calling and texting; delivering compliments every morning, along with highlights of Hall of Fame safety Brian Dawkins.

Mathieu needed time to think. He didn’t plan to sign with another team until July or August. He needed to tune his body and, more importantly, his mind. He went back to LSU and spent a week mentoring the current Tigers, then drove southeast, toward home. While just chillin’, an unfamiliar number from the most familiar area code popped up on his cell phone: 5-0-4. The caller identified himself as from the Saints front office.

The random phone call led to a visit. A photo from that visit went viral. Mathieu, after years of meditation, therapy and introspection, no longer feared New Orleans. But apprehension still lingered, mixing with promise, potential impact. He came to view his return as “what I’ve been growing toward the past 10 years, a test to put all that to use.”

What had changed over that decade? Everything, more or less. Eventually, he stopped focusing exclusively on the worst parts of the city. New Orleans had also shaped, taught and inspired him. He applied this new lens in looking back at the same events. The familial cocoon that protected him. The science teacher who pushed him. The neighborhood types who looked out for him. It wasn’t all bad, leg graveyard notwithstanding. Each positive memory was as much a part of him as his friends who died.

Maybe New Orleans had actually saved him. Maybe he could help save New Orleans.

To change how he viewed the city, he needed to change how he viewed himself. If he wanted to call out evils, what had he done to stop it? Change it?

He had bought his mother a house and invited her to games. He had written to his father, who remains incarcerated. He had let go. Had donated—$1 million—to the LSU football program that had kicked him off the team. Had hosted youth football camps, with Payton’s assistance, at the Saints facility. Paid for the funeral of a 9-year-old killed by a wayward bullet. And, through all that, he reconsidered what he meant by danger. His fears, he discovered, stemmed from being unsure about his future, his track record, his legacy.

In early May, Mathieu sat on a stoop in the Fifth Ward after signing a three year deal with the Saints worth up to $28.3 million. (Payton, who left the Saints in January, sent perhaps the best text message in the history of text messages: smh.) A close friend sat next to Mathieu; 30 years had passed and their hometown hadn’t changed that much. The friend pushed, reminding him of the tragic history they shared, how many they knew came back and fell into old habits.

The men, both hardened, exchanged knowing looks and head shakes, momentarily stunned into silence. Mathieu broke the trance. It would be hard, he told his friend, but after all he had endured—and all he had changed—he couldn’t worry about that cycle beyond his only choice available: to break it. “I can be one of the people who comes back and is successful,” he says.

Kevin C. Cox/Getty Images

Two months after signing, before the real tests begin, Mathieu oversees the field at the practice facility he now calls home. Except it’s not his teammates scrambling about but 300 local youth, kindergarten through ninth grade, there for a free camp.

History hangs all around them. Division title banners. A Super Bowl championship mural. An oversized picture of Will Smith. As Mathieu covers the entire field, just like in his day job, either Junior or Mila is always at his side. Asked later if this was intentional, his eyebrow raises. “How’d you know that?” He wanted to show the campers more than the Super Bowl champion who came home. “We all need a father,” he says. “It just helps the spirit, man.”

Mathieu’s high school coach, Del Lee-Collins, surveys both the camp and the homecoming landscape from a distance, and he sees something resembling his favorite dish. The fans. The star. The changes. The interest. The homecoming. The possibilities ahead. It’s a lot to mix together, perhaps messy and nonsensical at first. But if properly combined and artfully cared for, well, the possibility is perfection. “Like one big pot of gumbo,” he says with a laugh.

The diehards, oh, they love this. Carville explains: New Orleans isn’t for everybody, but when the city falls in love, it falls to the bottom of Lake Pontchartrain. “We weren’t Anthony Davis’s kind of town,” Carville says. “But we are the Honey Badger’s. Frankly, we’d rather have him.” Why? “We’re the most redemption-oriented place in the world. There’s no story of New Orleans without that.”

Here it is. The final stop. He’s back, but he’s not the same as when he left, hence all the changes that must be implemented. The Harrah’s he won’t visit. The craps games he won’t shoot. The circle he refuses to expand. The city he won’t live in, as he hunts for a home in the suburbs, just far enough removed. The people he carries with him in that graveyard on his leg.

In regular sessions this spring with Donny Starkins, Mathieu’s own Donny the Yogi, they uncovered the perfect analogy: The essence of meditation is coming home. It worked in a micro sense, in the actual exercise, to focus on breathing and note distractions and let them go to regain focus. People often mistook the practice for an exercise in thought. But it’s really an exercise in noticing, in awareness, in letting go; breath as a bridge between body and mind, an access point into the present, where past harm doesn’t matter and future worries don’t exist.

It’s about the body coming home to where the heart is.

With Jain, his body/mind coach, Mathieu is training his parasympathetic nervous system, focusing on lowering his heart and breathing rates by measuring frequencies throughout his body. This system was designed with input from Russian and German scientists and refined over three decades. Jain calls the spots they measure “energy points” in Mathieu’s tissues, organs and joints. Higher frequencies indicate emotional baggage, deeply held trauma. Once identified, they can be addressed, through changes in diet, healing techniques and physical therapy. The point, Jain says, is to attack the deep stuff, untangling what had lingered for years.

The peak of Mathieu’s career, he says, is still upcoming.

The hard part begins now. “Gotta come home, right?” Mathieu says, as if he’s still trying to convince himself. That he’s LeBron James, returning to Ohio. That it will all be fine.

Mathieu missed the first six days of training camp, due to what the team described as a “personal family matter.” Regarding his absence, he cited a need to take care of himself from a mental health perspective. But he made it into camp, claimed his starting spot and starred in the Saints’ opening win over the Falcons. In fact, his fumble recovery ignited the team’s comeback victory, setting up his first home-while-actually-home game, on Sunday against the Buccaneers.

It’s different, this homecoming. It’s glorious. It’s terrifying. He left New Orleans as a young adult soon to lose his way and returns as a father of three. He departed disgruntled and comes back enlightened. He left fearful and returns not with the resolve of someone who had conquered their fears but one who learned to navigate them.

A return home, like his life, is as messy and intricate as the city that’s charmingly problematic. Others can pretend his return is simpler, because it’s comfortable to look at it that way, palatable and polite. Mathieu, having found beauty in the struggle, the joy of a city that endlessly celebrates what it does have, must live in the complexity. He must confront it, deploying his most valuable instinct, for the final ride.

Mathieu signed his deal at the Saints facility in early May—as he did, a monitor hanging above his head read “welcome home.” He understood the significance of the date. So did team executives. There it was, the New Orleans area code delivered with a wink from the cosmos.

5-0-4—the date that a homecoming unlike any other had commenced.

• Can Buck and Aikman Save Monday Night Football?

• Joe Burrow and Cincinnati’s New Normal

• Gabriel Taylor Is the Late Sean Taylor’s Brother—and Maybe His Successor

• She Kicked for Vanderbilt, and Then Things Got Hard