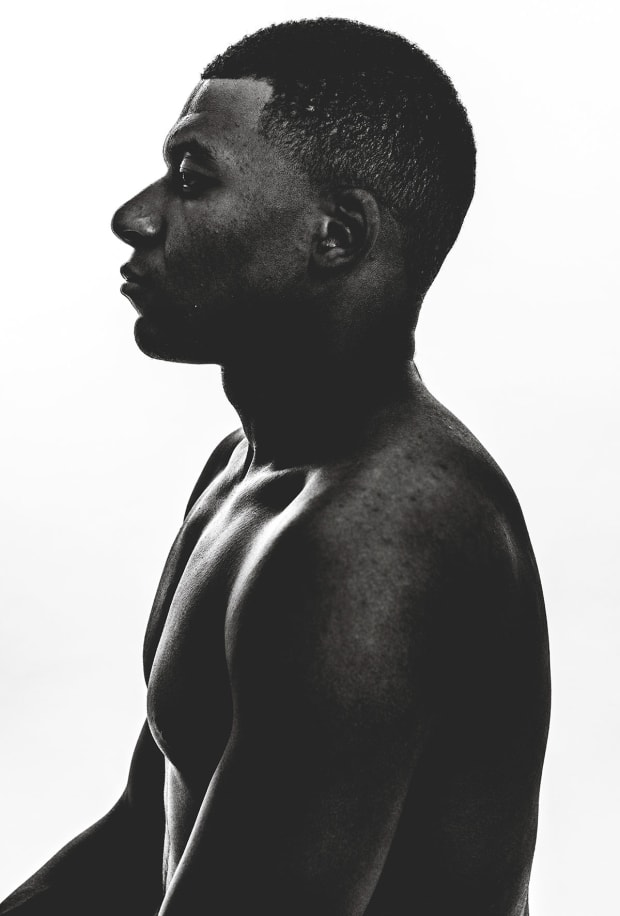

Winning the World Cup at 19 and becoming the world’s most expensive player by 23 comes with spotlight and scrutiny. And the France star is ready for more.

Emmanuel Macron hails from the far north of France, but a significant piece of his heart belongs to the south. The politician is a lifelong fan of Olympique de Marseille, the storied Mediterranean club that has been eclipsed in recent years, having won its last national championship, a record-tying 10th, back in 2010.

The wait for an 11th title is all the more agonizing for supporters like Macron, because the team that’s replaced L’OM atop Ligue 1 is its archrival, Paris Saint-Germain. Yet this past winter and spring, in a noteworthy example of choosing patriotism over partisanship, Macron committed himself to extending Marseille’s drought.

He called Kylian Mbappé. Then called him again.

“It was a few calls,” Mbappé says, laughing. “It was like December, January, February, March …”

LEBRECHTMEDIA/Sports Illustrated

Mbappé, the 23-year-old PSG star, was the focus of a protracted, headline-grabbing tug-of-war between his hometown team and mighty Real Madrid, soccer’s most famous and decorated club. Mbappé was heading toward free agency, and, for many, his choice between staying in Paris and leaving for Madrid, or between Ligue 1 and La Liga, was about a lot more than where he’d spend the next few seasons.

It was about weighing childhood dreams—he’d fantasized about wearing Madrid’s iconic white since adolescence—against adult reality. It was a referendum on PSG’s ambitious project, which is financed by Qatar’s near-bottomless sovereign wealth fund, and the French league’s fading stature among Europe’s elite. And it was about balancing Mbappé’s calculated designs on global renown with his increasing importance to his complicated country.

“[Macron] called and said, ‘I know you want to leave. I want to tell you, you are also important in France. I don’t want you to leave. You have an opportunity to write the history here. Everybody loves you,’ ” Mbappé recalls. “I said I appreciated it, because it’s really crazy. The president calls you and wants you to stay.”

Speaking to reporters in June, Macron acknowledged the conversations and said, “I believe it is my responsibility, as president, to defend the country.”

Mbappé is an asset worth fighting for, even if he’s in a rival club’s colors. It was evident early that the boy from Bondy in the diverse, working-class Paris suburbs, or banlieues, was special. The son of a Cameroonian coach and a French Algerian former handball player, Mbappé spent a lot of his childhood on the small, concrete pitches of the banlieues, being coached by his dad at the local youth club and playing FIFA with his brothers. (Mbappé’s hands-in-the-armpits goal celebration was inspired by his brother after scoring in the video game.)

“You play football all the day and all the night. It’s part of the culture of the country,” Mbappé says. “There is no pressure. No, ‘You have to become professional.’ It’s all ambition, but there is no pressure. It’s all about to have this passion in your heart.”

At 13, Mbappé was already being courted by Real Madrid. He took a trip to the Spanish capital to train and meet his idols—forward Cristiano Ronaldo, whose face covered the walls of his bedroom, and sporting director Zinedine Zidane, whose trademark bald spot Mbappé wanted carved into his own scalp. After turning pro and winning his first Ligue 1 title with AS Monaco, he returned to Paris and PSG in a €180 million deal that made him the most expensive teenage player of all time.

As the 2018 World Cup kicked off, Nike posted billboards, including one on the Stade de France, featuring a smiling Mbappé and reading, ’98 A ÉTÉ UNE GRANDE ANNÉE POUR LE FOOTBALL FRANÇAIS. KYLIAN EST NÉ.’

“ ’98 was a great year for French football. Kylian was born.”

LEBRECHTMEDIA/Sports Illustrated

In the summer of 1998 at that same arena in the banlieue of Saint-Denis, where the poverty rate is twice the national average, Les Bleus finally won the World Cup. They were the “Black-Blanc-Beur,” the collection of Black, white and Arab players who led France to overdue glory with a 3–0 thumping of Brazil in the final. Inspired by the brilliant Zidane, the Marseillais son of Algerian immigrants, and featuring multiple minority stars and a sprinkling of men from the banlieues, that French side was supposed to herald a national reckoning regarding race, immigration and the potential for marginalized citizens to contribute to French society.

A generation later, the banlieues’ impact has proved to be seismic. Eight members of France’s 23-man squad at the 2018 World Cup in Russia hailed from the Paris suburbs, each of them the son of at least one immigrant. While the likes of N’Golo Kanté and Paul Pogba helped Les Bleus put a stranglehold on opponents, it was Mbappé who ripped them open. He stretched the field, adding welcome dynamism and excitement to an ultratalented team that spent a lot of the tournament in second gear.

Mbappé’s speed, skill and effervescent confidence were too much for Lionel Messi’s Argentina in an epic 4–3 round-of-16 encounter, during which Mbappé drew a penalty and scored twice. He then became the first teenager since a 17-year-old Pelé to score in a World Cup final, a 4–2 triumph over Croatia. Mbappé finished his debut World Cup with a gold medal, four goals, three displaced vertebrae (suffered three days before the semifinal) and the best young player award. Macron embraced and kissed Mbappé during the rain-swept trophy ceremony in Moscow.

The boy from Bondy was the prince the ad had promised, football’s heir apparent to Zidane, Messi and both Ronaldos. Mbappé was racing into the pantheon.

“That changed my life. After that World Cup, everything was different, because all the world [was] watching. And when you do something good it’s been crazy after,” he says. “I was famous before the World Cup, but not like this. It became crazy. It took me some time to [learn] to stay calm.”

TF-Images/Getty Images | Michael Regan/FIFA/Getty Images

Expectations soared. Mbappé hit his stride with PSG, winning multiple French and Ligue 1 player of the year awards. Meanwhile, Les Bleus were favored to claim the postponed European Championship in the summer of 2021. The margins at the highest level are fine, however, and boys from the banlieues tend to walk that tightrope. France lacked its World Cup spark at the Euro. Unconvincing during the group stage, the world champions then blew a late two-goal lead to Switzerland in the round of 16, and Mbappé missed the decisive penalty kick in the ensuing shootout. He finished the competition with no goals and so endured the sad phenomenon that seems to be increasingly popular across European soccer: a torrent of online racial abuse.

When you win, you’re French. When you don’t, you’re something else.

“Criticism of players for making mistakes and getting things wrong is a part of the spectacle of football. You come to boo and hiss,” says Lilian Thuram, a member of France’s 1998 Cup-winning team, through an interpreter. “But more fundamentally, the success of those who are not supposed to succeed in society, particularly people of color, that’s upsetting to some. And when Kylian misses a penalty, they’re waiting for that mistake.”

Thuram, 50, may have been the most complete defender of his generation. An immigrant from Guadeloupe and a product of the Paris banlieues, Thuram also came alive during that summer of 1998, anchoring France’s back line and scoring twice in the semifinal. Ahead of the 2022 World Cup, the robust but elegant defender still holds the record for Les Bleus appearances. His second career has been just as impactful. Thuram is an author, lecturer and one of France’s most visible antiracism activists. He continues to fight for team Black-Blanc-Beur nearly a quarter century after that promised reckoning.

“It’s all part of a wider racist backlash against players like Kylian Mbappé,” Thuram says. “[Some people] don’t think they should escape from the banlieue.”

A post-Euro meeting with French Football Federation president Noël Le Graët, who’s been the focus of misconduct and harassment investigations and has been quoted denying the existence of racism in soccer, was brief and unproductive. Mbappé felt the FFF wasn’t backing him sufficiently. Not all presidents are so supportive, and so Mbappé felt he had no choice but to quit Les Bleus just a year-plus before the Qatar World Cup.

“I said, ‘I cannot play for people who think I’m a monkey. I’m not gonna play,’ ” Mbappé says. “But after, I take the reflection with all the people who play around me and root for me, and I think it was not the good message to give up. Because I think I’m an example for everybody.

“This is the new France. … It’s for that, that I didn’t give up the national team. Because it is a message to the young generation to say, ‘We are stronger than that.’ ”

LEBRECHTMEDIA/Sports Illustrated

Mbappé was raised eight miles northeast of central Paris, at the heart of the Île-de-France yet also, somehow, on the national periphery. Lots of problematic labels are affixed to the banlieues, with their gritty tower block housing, substantial immigrant populations, rough economic conditions, high unemployment and occasional violence. Bondy was toward the center of the 2005 riots triggered by the death of two teenagers who were electrocuted while hiding from the police in a power substation following a pickup soccer game. It can be a place where residents feel neglected, oppressed and isolated.

But they can also feel French.

“I feel French because I was born in France, and they gave me this opportunity to grow up normally,” Mbappé says. “People think a lot of things about the banlieue without going there. I learned a lot of values there. When I talk about it to people, they don’t think it’s real when I say, ‘Yeah, there is no problem there. There is not. It’s like everywhere.’ ”

Mbappé’s upbringing, which included flute lessons and Catholic school, was relatively comfortable thanks to his diligent parents, who remain his closest confidants and advisers (he has no agent). That stability, plus a well-organized local athletics structure—the banlieues are like a footballing atom smasher ringing Paris that attract thousands of full-time coaches and scouts from around Europe—offered Mbappé an ideal launching pad. He delights in telling a story about his banlieue values that hinges on a meeting with José Mourinho at a FIFA awards ceremony, where Mbappé greeted the Portuguese coach and then each of his guests.

“I came and I say, ‘Hello,’ to José Mourinho because I know him—he is José Mourinho. But I say hello even to the friends, and José Mourinho did an interview and said, ‘I was shocked that Kylian came and say, ‘Hello,’ to all my friends,’ ” Mbappé says. “And after, people asked me and I say, ‘It’s what I learned in the banlieue. … I was brought up with respect.’ If you come and take the hand, you take the hand of everybody.”

His pride and affection for the place, and his experiences representing France both triumphant and distressing, have bound Mbappé to his home in ways he may not have expected as a teen. That became clearer this spring as Macron phoned and then phoned again, and as the pressure to decide between Madrid and PSG increased. Most reports said Mbappé’s departure was inevitable, sealed but not signed, and when Madrid eliminated PSG from the Champions League in early March on the way to a record 14th European crown, it seemed like an omen.

PSG had Qatar’s billions and its acclaimed attacking trident of Mbappé, Messi and Neymar. But it was founded in 1970—the club is a toddler on the global stage—and it won just two domestic league titles before the 2011 Qatari takeover. A decade later, PSG has become a massive fish in a modest pond that, despite its largesse and ambition, had advanced to just one Champions League final (a ’20 loss to Bayern Munich).

Matthieu Mirville/ZUMA Wire/Imago Images

Pedigree often makes a difference at the highest level. It tilts the field. Despite decades of elite talent production, Ligue 1 teams have lifted just a single European Cup (Macron’s Marseille in 1993). That inexplicable underachievement, and the accompanying derision, stands in contrast to the tradition and allure of Real Madrid, which seemingly wills itself to victory time after time. It did so with Zidane in the early 2000s, and Los Blancos now feature French stars like striker Karim Benzema, the European player of the year, and midfield prodigy Aurélien Tchouaméni. It’s always been the place to be.

That gravitas enticed Mbappé. But it’s one thing to win a 15th continental crown for Real Madrid—to become another in a lengthy line of conquerors—and quite another to win the first for Paris. Not many men from anywhere beyond Barcelona or Munich have won both the World Cup for their country and the Champions League for their hometown club.

So for a young man who never wanted to put limits on his ambition, an unexpected perspective emerged. Mbappé flourished during the 2021–22 campaign despite the scrutiny, leading Ligue 1 in goals and earning its player of the year award for the third time. He was the only player cheered when the club returned to the Parc des Princes following its loss to Madrid. Mbappé soon realized that he could be the centerpiece or catalyst, and that achievement absent Real’s aura might mean even more. That high-risk, high-reward quest would quickly test his resolve, patience and maturity.

“I’m not scared. I’m ready,” he says. “I always talk about my ambition, what I want to do, and now it’s time.

“In Paris, the book is fully white. What an opportunity! You have to think differently. Of course, it was easier to go to Madrid. But I have this ambition. I’m French. I’m a child of Paris, and to win in Paris, it’s something really special—really special. It writes your name in the history of your country for life.”

His name was everywhere, anyway. This was LeBron James’s 2010 Decision in reverse. The new contract was eye-watering—three seasons and worth north of €250 million. Mbappé is now the highest-paid player in the world by a good margin (Messi and Neymar rank second and third). But he bristles when it’s suggested that his commitment was inspired by money. Mbappé was getting paid regardless, and he’ll be a free agent again at just 26. Instead, he claims, it was about opportunity.

“You can stay here to have success,” he says. “For us it’s a big message, because when I announced I stay, a lot of things change in the mentality of people. People start to say, ‘Yeah, we don’t need to go out. You don’t need to leave the country.’ ”

That’s a bold mission for a boy from the banlieues. But Mbappé believes times, and many attitudes, are changing. His generation is connected, global and idealistic, and Mbappé’s perspective on the platform his success affords reflects those modern attitudes. He aspires to the honors and heights of Messi and Ronaldo (neither has won a World Cup, but they’re indisputably the faces of the game), although Mbappé is cut from a different cloth. He may have a superstar’s conceit at times, but he’s already more public and proactive beyond the field than other, older greats.

Mbappé earned plaudits in 2018 when he donated his $500,000 World Cup check to the charity Premiers de Cordée, which gives free sports instruction to disabled and hospitalized children in France, and he continues to part with his national team fees even while battling the FFF over the governing body’s insistence that players make appearances for sponsors they may not support—fast food and gambling companies, in Mbappé’s case. In ’20, he launched a foundation, Inspired by KM, that aims to support 98 (there’s that number again) Parisian children ages 9 to 16 “until they begin their working lives.”

This summer, with the World Cup pushed to November, he visited the U.S. on perhaps the most high-profile marketing trip ever taken by a European footballer. Mbappé walked the red carpet at the NBA draft, kicked field goals with the Rams and announced the launch of a production company, Zebra Valley, that will produce and distribute content created by young and diverse artists. The outfit has already signed deals with WME Sports and the NBA. Mbappé, who is trilingual, is involved in meetings and wants to learn the business, something he doesn’t have to do this at this stage of his young career.

Mbappé will be criticized and scrutinized, especially as he becomes more important to France and PSG, as his contract ripples through the football economy and as he extends himself beyond the field. Tussle with Neymar over a penalty kick, as he did in PSG’s second Ligue 1 game of the new season, and global social media platforms, newspapers and talk shows grind to a halt. He’s been accused of demanding a say over PSG’s front office and player personnel (he denies it), and was linked to an outrageous September story concerning allegations from Pogba’s brother that the midfielder hired a witch doctor to curse Mbappé.

LEBRECHTMEDIA/Sports Illustrated

Then, in early October, a wave of reports (dismissed as “rumor” by Mbappé’s camp to Sports Illustrated) claimed that Mbappé was already so frustrated by PSG’s delay in keeping promises related to tactics and player personnel—help he believes he needs to fulfill his mission—that he was angling for a January exit. His desire to be the focal point, the man who’d lead PSG to the promised land, quickly raised the personal and public stakes to a fever pitch.

“Kylian is aware of these pressures and he can deal with them. He has the

mentality to face up to this and to overcome those challenges and critiques,” says Thuram, whose sons, Marcus and Khéphren, intersected with Mbappé early in their careers.

“Part of Kylian’s public profile and why he’s so well known is because people know he does so much more than football. It is part of why he’s such a celebrated figure,” Thuram adds. “We talk a lot about the people who criticize, but most people love him. They absolutely love him.”

That’s why he was worth those presidential phone calls and worth Macron’s supporter sacrifice. Mbappé is now the flag carrier for his generation, for the banlieues and for a France still wrestling with old divisions. He embodies youthful potential, ambition and pride. He’ll try to make Les Bleus the first team to win back-to-back men’s World Cups in 60 years. The buildup has been brutal, with the aforementioned scandals and distractions piling up alongside multiple injuries to key contributors, including Pogba and Benzema, and surprising on-field setbacks. Historic and recent trends suggest this might not be France’s year, despite its obvious quality.

If this World Cup doesn’t go well, Mbappé will have other chances, but he has no intention of wasting another opportunity to blaze a new trail.

“It’s been my mentality since I’m young, is always to do more, to push the limits. For me it was not the end when I won the World Cup. It was the first chapter of something crazy,” he says.

“It’s so hard” to win two in a row, he concludes. “But if you want to write the history, you have to do something nobody do. So we’re going to try. I think we have a good team. We’re a good collective. The manager is the same. And we have the country behind us.”

• Straus: For Youthful USMNT, Program’s Rebuild Wasn’t Child’s Play

• Gonzalez: Christian Pulisic vs. the Haters

• Straus: By George, Tim Weah Is Humbly Reaching His Potential

• Falkenheim and Prewitt: When Phony Environmentalism Comes to Sports