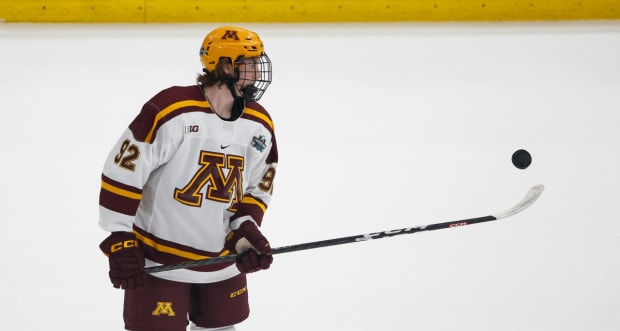

On Nov. 25, 2022, University of Minnesota centerman Logan Cooley had the puck on his stick and plenty of space behind his opponent’s net. As he skated back above the goal line, his path to the net was cut off by a defenseman, so he executed a 180-degree turn on a dime and skated back into the still-vacant ice behind the net with the puck on his forehand.

“Any time I’m behind the net and have a little space, I’m kind of thinking about it,” says Cooley, who was picked third in last year’s NHL draft by the Coyotes.

John Russell/NHLI/Getty Images

“It” is the Michigan-, or lacrosse-style goal. Without breaking stride, the Gophers star slid the blade of his stick under the puck, then lifted it waist-high as he skated back around the net. As he turned the corner, he whipped his stick past the Arizona State goalie and deposited the puck under the crossbar.

Even at high levels of hockey, the puck is mostly handled and passed on or near the ice where it’s easiest to control. Modest forays into the z-axis, like saucer passes or deflections, can introduce added unpredictability to a sport that’s usually already too chaotic for comfort. But while Cooley’s particular display of skill and audacity was unusual, it is increasingly common, especially among hockey’s up-and-coming elite.

On Dec. 27, the presumptive first and second picks in this year’s NHL draft, Connor Bedard and Adam Fantilli, both attempted the Michigan in the first period of Canada’s first game of the IIHF World Junior Championship. And caused quite a stir doing so, when both failed and heavily favored Canada suffered an upset loss to Czechia. On New Year’s Day, Northeastern University forward Jack Hughes (son of Montreal Canadiens GM Kent Hughes, no relation to the New Jersey Devils center of the same name) scored a Michigan goal against Harvard.

On Jan. 12, then 14-year-old Nela Lopušanová, playing for the Slovakian national team, executed a Michigan goal against Sweden at the U18 women’s world championship. “It is a routine move for me,” Lopušanová told Hailey Salvian of The Athletic afterward. “It was easy to do.” Six weeks later, 18-year-old Matvei Michkov, one of the top candidates to go third behind Bedard and Fantilli, scored a Michigan goal for HC Sochi of the KHL. And a month after that, Columbus Blue Jackets center Kent Johnson became the fourth player ever to score a lacrosse goal in the NHL.

Johnson’s goal came at the end of a lost season for one of the worst teams in the NHL, making his Michigan goal a low-risk enterprise. But in Game 3 of the Atlantic Division semifinal against Boston, Florida Panthers winger Matthew Tkachuk went behind the net, shoveled the puck onto his stick blade, and tried to score the first playoff Michigan goal in NHL history. The puck never got settled, and the attempt went for naught.

Tkachuk nearly finishes a Michigan 🤏 pic.twitter.com/KsAQyi3VIH

— Sportsnet (@Sportsnet) April 22, 2023

But with Florida’s upset series win over Boston, he’ll have more chances. And he won’t be the last to try.

As recently as five years ago, the Michigan move was a novelty act, a trick shot suitable for middle schoolers playing street hockey. It would show up maybe once a decade in college or major junior and was unheard of in the NHL. Now, after more than a century of two-dimensional thinking, a generation of young stars is looking at the vertical space above the ice and wondering why it’s been left unexplored for so long.

Richard T Gagnon/Getty Images

Like most fads that are taking off among Gen Z, the Michigan is actually from the 1990s. Bill Armstrong, who played at Western Michigan University before entering the AHL in ’89, gained minor notoriety for scoring a handful of lacrosse goals in the minors.

But Stigler’s law of eponymy holds that no scientific breakthrough is named after the person who discovered it, and the Michigan is no exception. During the offseason, Armstrong would return to his hometown of London, Ont., where he trained with a number of other local players. It was there that a University of Michigan winger named Mike Legg spotted Armstrong working on the move and learned it himself.

After months of preparation, Legg became an overnight celebrity when he used it to score in a televised NCAA tournament game March 24, 1996. Even though the Michigan, as it quickly came to be known, instantly became a part of hockey folklore, neither Armstrong nor Legg was able to translate the skill into an NHL career. Legg played professionally in Europe and the minors for a few years, while Armstrong’s NHL career lasted exactly one game.

In 2003, a 16-year-old Sidney Crosby scored a Michigan goal in the Quebec Major Junior Hockey League, and drew the ire of Don Cherry for attempting such a hot-dog move. Hockey tends to have a conservative culture that teaches conformity; nails that stick out tend to get pounded down, often literally in the rough-and-tumble 1990s.

Even supporters and practitioners of the move agree there’s a time and place for it. For a player as audacious as Tkachuk, that time is in the playoffs against a team coming off one of the best seasons in NHL history.

Most players have to be a little more discerning. When Bedard and Fantilli came up empty on the Michigan at world juniors, their teammate Dylan Guenther—who had himself scored a Michigan goal in the WHL—said, “We’re not going to Michigan our way to the final.” And sure enough, nobody else on the team tried the move as Canada ran the table and won the gold medal.

In addition to the normative argument against trick plays of any kind, the Michigan is inherently a low-percentage move in a sport that does not offer many clear scoring chances. There’s an opportunity cost to a technique that requires so many moving parts to link up.

The Michigan requires space, timing, speed and a fair bit of luck to get the puck off the ground, around the corner of the goal, and into the net without either hitting the goalie or coming in over the crossbar, which would invalidate the goal on the grounds of the puck being played with a high stick.

Still, the conditions do sometimes line up. Both Cooley and Hughes pointed out the importance of attempting the move early in a period, when the ice is fresh.

“There’s been a few times I tried to scoop it, and it rolls right off your stick,” Cooley says. “Any time you have smooth ice, a fresh tape job and a little bit of wax, it definitely makes it a lot easier.”

Every interested hockey player on the planet now has more than 25 years’ worth of tape on the Michigan, so it was only a matter of time before they refined it to a science. But learning the Michigan takes good hands; actually trying it in a game takes guts.

Kirk Irwin/Getty Images

Hockey is not the only sport that took a while to recognize that a flashy, risky-looking skill had inherent practical value. A Babe Ruth or Steph Curry remains a unique figure only until other athletes realize their approach can be replicated. So, too, with the Michigan in hockey; once enough players understood the move and refined its application, the dam was always going to break.

In 2011, Mikael Granlund scored the highest-stakes Michigan goal since the original, when he put in the opener in Finland’s world championship semifinal victory over Russia.

While Legg and Crosby had gathered the puck while it was settled behind the net, Granlund put a new spin on the move, gathering the puck at speed, much like Cooley did a decade later, before slotting the puck over the goaltender’s shoulder.

Granlund has now played 11 seasons in the NHL with the Minnesota Wild, Nashville Predators and Pittsburgh Penguins. But when he scored his Michigan goal he was just 19 years old and still a year and a half from making his NHL debut. The Michigan was something he’d worked on as a kid.

“I picked it up from VHS tapes my coach gave to me,” Granlund says. “It was such a cool thing. … I used to do it in floorball and street hockey, just pick those things up and practice. When game time came, it was just instinct, I guess.”

When Legg put the Michigan move on TV for the first time, highlight reels didn’t exist the way they do today. It could take months or years for a specific play to get put on tape and filter across the world to a young player like Granlund. Now, more games than ever are either broadcast on TV or streamed online, and anyone in the world with access to Twitter, YouTube, TikTok can see a player score a Michigan goal within minutes of it happening.

Hughes says he learned the Michigan years ago but considered using it in a game only after watching how and when other players pulled off the move. “You can see how they do it, in which scenarios,” he says. “[Now] I see eight or nine year olds doing it on Instagram when I go on my phone, so it’s definitely becoming more common.”

It’s hard to teach an old hockey player new tricks, but kids are impressionable. Nashville Predators forward Filip Forsberg saw the Michigan for the first time in person around the same time Granlund scored his goal at worlds. Forsberg was a teenager, riding the bench while on loan to Leksands in the Swedish second division, when an opposing player broke it out. At lower levels, up to and including college and world juniors, an unusually skilled player like Lopušanová, Cooley or Bedard might just be so much better than the opposition that they can operate with freedom that no NHL player enjoys.

“He just came down the wing, went behind the net and scooped it in, and went back to his bench,” Forsberg says. “Barely any celly or anything. I was sitting on the bench at 16 years old, like, ‘Holy crap, what just happened?’ That’s the first time I saw it. Guys would be toying with it growing up, doing that flex with spins and all kinds of crazy s—, but no one had ever pulled it off in a game.”

Greg Thompson/Icon Sportswire/Getty Images

For almost a quarter century, the Michigan move was consigned to college, major junior and international play, with videos of varying quality bouncing around the internet like evidence on a Bigfoot truther message board. But it had never been done at the NHL level, where the time and space required to set the Michigan up are hard to come by, and the scrutiny that comes with failure provides a powerful deterrent.

“There’s defenders all over you, and trying to put the puck on your stick and into the back of the net while you’re in full motion like that; it’s one of the hardest things to do,” Cooley says.

But today’s young NHL players and top prospects have a different conception of what’s possible on a hockey rink than players who were born in the 1980s and early ’90s. And North America’s top hockey league is finally becoming more hospitable to a quick-thinking, creative and highly skilled style of play. Crosby’s rookie year was the first NHL season to be played under the wholesale rule changes designed to make the game faster and more open after the ’04–05 lockout. The current generation of highlight-making stars—Connor McDavid, Auston Matthews, Cale Makar—isn’t old enough to remember the dead puck era of the late 1990s and early 2000s. Cooley, born in May ’04, wasn’t even alive then. These players weren’t just born to push the envelope; they have a completely different idea of where the envelope is.

“The league has changed. I do think it’s for the better with the mentality,” Forsberg says. “It used to be very serious. You couldn’t really have fun with it. Now guys are bringing more personality. …The skill stuff that’s come in, I think that’s similar. Guys come in and be more creative—it almost forces the older players to be more creative. Not necessarily to try to score lacrosse goals, but you see people making plays.”

On Oct. 29, 2019, Carolina Hurricanes winger Andrei Svechnikov, then 19 years old, brought the move to the big leagues. He carried the puck behind the net, suddenly reversed his path, and in one fluid motion brought the puck from the ice, past the ear of Calgary Flames goalie David Rittich, and into the roof of the net.

By that point, it was less a question of if someone would score a Michigan goal in the NHL than when and who. The whole process took less than three seconds, and yet play-by-play announcer John Forslund immediately identified it as a “lacrosse move” while calling the play. Svechnikov tried the move again repeatedly in the weeks that followed, but few have been able to follow in his footsteps.

So far, only four players have scored a Michigan goal in an NHL game: Anaheim Ducks center Trevor Zegras, Svechnikov, Forsberg and Johnson. (Johnson, a University of Michigan alum, scored his goal on March 24, 27 years to the day after Legg’s.)

When Forsberg scored his Michigan goal in January 2020, everything fell into place for him. He was skating behind the Edmonton Oilers’ net from right to left when goalie Mike Smith was slow covering the far post. If Forsberg, a righthanded shot, had tried a conventional wraparound he would’ve had to do so on his backhand. Whereas once he got the puck off the ground and onto the blade of his stick, he was able to maintain control long enough to score.

It was hardly his first attempt.

“I’ve had a couple of chances,” says Forsberg, who estimates he’s tried it at least 10 times with only one success. “I remember one in particular when I tried it against Dallas, and [goaltender Anton] Khudobin basically dove over like a soccer goalie and covered the top of the net. … I had one off the post against San Jose, maybe a handful more that have been poor attempts. Obviously the one in Edmonton might not have been the cleanest one since it went low, but it did go in.”

Attempts like Forsberg’s have acted as a permission slip for players at every level of hockey.

“I learned how to do it a long time ago, probably five years ago, before you’d really see it very often,” Hughes says. “But I never thought, ‘Oh, I’m going to try it in a game.’ I just thought it’d be cool if I ever could do it.”

But once Hughes saw the Michigan being done more frequently at higher levels, he changed his mind.

“They’re doing it in the NHL; it’s definitely possible.”

Bill Wippert/NHLI/Getty Images

The Michigan remains a low-percentage move, but in high-level hockey, where goalies routinely stop at least 90% of shots on goal, most shot attempts are low-percentage moves. And sometimes the Michigan is legitimately the smart way to go.

“It seemed at the time like it was really my only option,” Granlund said of his Michigan goal for Finland, which broke a scoreless tie in the second period with a shot at a world championship gold medal on the line. “I got the puck, got to the net, and found out nobody was expecting me.”

Hughes says his coaches have more or less given him the green light to score by whatever means he finds expedient, but even he says there are limits.

“If I force it when it’s not there, turn it over, or maybe another play is there and I do [the Michigan] instead, they might not be too happy,” he says. “But they want me to be creative.”

By this point, enough people have tried the Michigan that a number of different approaches and techniques are available to be studied. While describing the different approaches to the Michigan, Hughes singled out Forsberg’s goal as particularly impressive.

“People press their stick down on the ice, the puck goes on edge and then it’s on the stick,” Hughes says. “People scoop it, which I think is probably the easiest way. And then there was Forsberg, who picked it up with the toe of his blade while he was flying behind the net,” Hughes says. “I think that’s by far the hardest way to do it.”

“My curve has a pretty big toe on it,” Forsberg explains. “Sometimes that makes it easier to just dig in under [the puck]. The more common way is obviously to flex it, like Svechnikov did, where you put all your force on your stick and pull it up that way. I just personally don’t think I was ever very good at it.”

The three options Hughes outlined aren’t exclusive, and players are finding new variations on the skill all the time.

Hughes, who seems to have an encyclopedic knowledge of Michigan attempts, highlighted an unsuccessful 2021 attempt in which Crosby tried to pick the puck up on his backhand. “The way he did it was crazy,” he says. “I don’t think many people can do that.”

Even though it’s been executed only four times in NHL history, the Michigan is a real enough threat that goalies and defenses are learning how to anticipate and stop it.

“In World Juniors, I tried it in an exhibition game against Finland; I pulled it up and everything and the goalie was right there,” Cooley says. “Players are getting so good at it, but now I think goalies are starting to get really good at reading it.”

And so forwards are now using the threat of the Michigan to set up countermoves. There was a 2019 assist by Matthews, who faked a lacrosse move in a Statue of Liberty–like play to set up a wide-open net for teammate William Nylander. And the most famous Michigan-related play since the original was not a goal, but an assist.

In December 2021, some six weeks before he’d score his own Michigan goal, Zegras set up behind the net, gathered the puck like he was going to attempt a Michigan, and instead of shooting he lobbed an alley-oop over the net toward a waiting Sonny Milano, who batted the puck in for what might be the most iconic NHL goal since a young Alex Ovechkin scored while laying on his back.

Every new innovation and counterinnovation puts more information on tape, and puts more puzzle pieces together for any young players who are watching. And the more players see what’s possible, the more they’ll try to build on it.

“I got inspired when I saw the Michigan—it made me go outside playing with the puck for a year,” Granlund says. “You go out there and you want to be like that, do something like that.”