This story is part of Sports Illustrated’s exploration of the ways sports and finance intertwine—from the NIL revolution to online betting, business-minded athletes and more. For more on sports and money, see SI’s October 2023 Money Issue.

Molipur, a village of 5,200 in India’s northwestern state of Gujarat, is not the kind of place where sporting dreams are made. Its knot of white-walled homes sits on scorching lowlands where, in summer, the sun burns the sky cobalt gray and presses livestock down onto their haunches. Not even the midday call of the muezzin, which rings from the village’s bell-domed mosque, coaxes more than a handful of souls outside.

Yet in May 2022, as temperatures soared above 110°, one Molipuri man toiled around the clock on a hangdog farming plot a five-minute walk outside the village, bound on one side by a reservoir and on the other by a grove of mango trees. The man’s name was Shoeb Davda, a 35-year-old beanpole of a bangle merchant and a father of five, with a drawn face and beard like a warbler’s nest. He’d recently returned from a two-month trip to Moscow, where he had become entangled with a group of shadowy but well-financed men. They had an idea, inspired by the rise of the Indian Premier League, a quick-fire, eight-week-long cricket tournament every spring watched by some half a billion people globally. The IPL attracted millions of punters from around the world to India’s national obsession—and the men suspected those fans would bet year-round. Were Davda to establish his own, livestreamed cricket tournament, they suggested, wagers would follow, and he could cleave a slice of the sport’s newfound betting riches for himself.

Illustration by Andrew DeGraff

It would not be easy: To attract online bettors, Davda was told, he would have to create something that looked like the IPL—down to the players, uniforms, equipment, broadcast quality and, toughest of all, a stadium. From nothing. It was a herculean, harebrained task. But Davda’s businesses had hit the skids, and his prospects for work in Molipur, filled with poverty, were hopeless. With his father having passed, he was the family’s sole breadwinner. He said yes.

Illustration by Andrew DeGraff

Several landowners turned Davda down before he convinced a local millet farmer to rent out his scrubby plot for about $3,000 a year. Davda mowed it into a parched but playable surface and pinned a flat, pale-green mat to its center as the 22-yard plain on which bowlers would pitch to batters. Three hours away in Ahmedabad, Gujarat’s largest city, he bought playing equipment: balls, protective pads and the wooden stumps and bails that constitute cricket’s physical strike zone. He also acquired five high-definition cameras, two LED screens, walkie-talkies and halogen lamps. With the help of a man named Saqib Saifi, whom the Russians had brought to Molipur from Meerut, a city near Delhi, Davda hooked the lamps to 10 poles dotted around the field’s edge. Now he could stage matches even after nightfall.

At one end, behind the batter’s eye, Davda erected a four-story scaffold to act as the principal camera gantry. A few yards away, in the mango trees’ dappled shade, he built a small tin scorer’s hut in which he installed a desk, chairs and the two screens, plus microphones he borrowed from a nearby Hindu temple. He raised standing speakers on both sides of the hut to pipe crowd noise onto the field. Everything was hooked up to a portable generator.

Improbably, by early June, after six weeks of labor, Davda’s field of dreams was ready to roll. A week before, just 65 miles away, 105,000 fans had packed Ahmedabad’s glittering new cricket stadium, named for Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, to watch the IPL final. Those grounds were to Davda’s stadium as the Taj Mahal is to a cowshed. But in tiny Molipur, the field was a miracle.

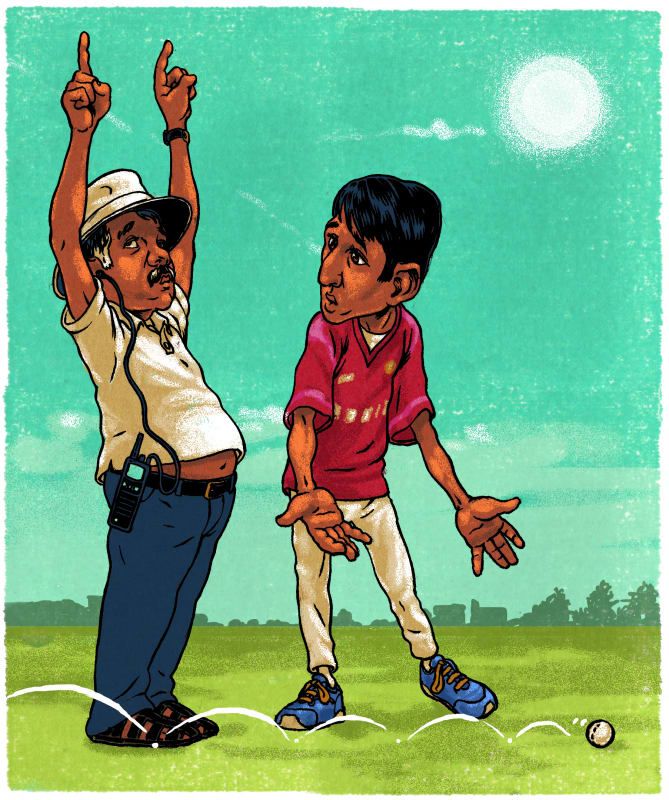

Davda enlisted two friends as umpires. Hiring 22 players was a breeze. Molipur is a stone’s throw from Modi’s hometown of Vadnagar but light-years from the urban development that is a hallmark of his decade-long rule. In that time, cities like Ahmedabad have been transformed, and India, now the world’s most populous nation with 1.4 billion people, has grown into one of its strongest economies. But Modi’s Hindu Nationalist vision has had little space for India’s more than 210 million Muslims, let alone those who make up a remote village like Molipur. Few of the town’s streets are paved, homes remain unfinished and jobs—especially post-COVID-19—are scarce.

When Davda was scouting for talent, a Molipuri lucky enough to work could expect to earn around three bucks a day. Davda offered them almost $5 per game, with each comprising a single innings of six “overs”—units of six deliveries—per side. A match would last around 45 minutes, and Davda aimed to play three daily. Even by the standards of the IPL’s 20-overs-per-side, or T20, matches, which usually run about two and a half hours, they were blitzes—and much faster than the sport’s marquee Test format, which can last hundreds of overs spread across several eight-hour days. More and faster games meant more money for the players—and more opportunities for bettors to part with their cash.

Sanjay Thakur heard about Davda’s tournament from a friend in the village. The idea smelled as funky as the farmhouses he mucked out for bottom-rate pay, and he thought it best not to tell his wife. But the money was too good to ignore. On June 8, 2022, Thakur captained a side in the inaugural match of Molipur’s “IPL,” donning the uniform of the Chennai Super Kings against a side dressed as the Mumbai Indians, both real IPL teams. In Davda’s livestream the teams were referred to by knockoff names, the Chennai Fighters and the Haryana Warriors, but no matter. Everything ran smoothly, and when it ended, the players hydrated and changed uniforms beneath the mango trees, taking on the identity of a pair of new teams.

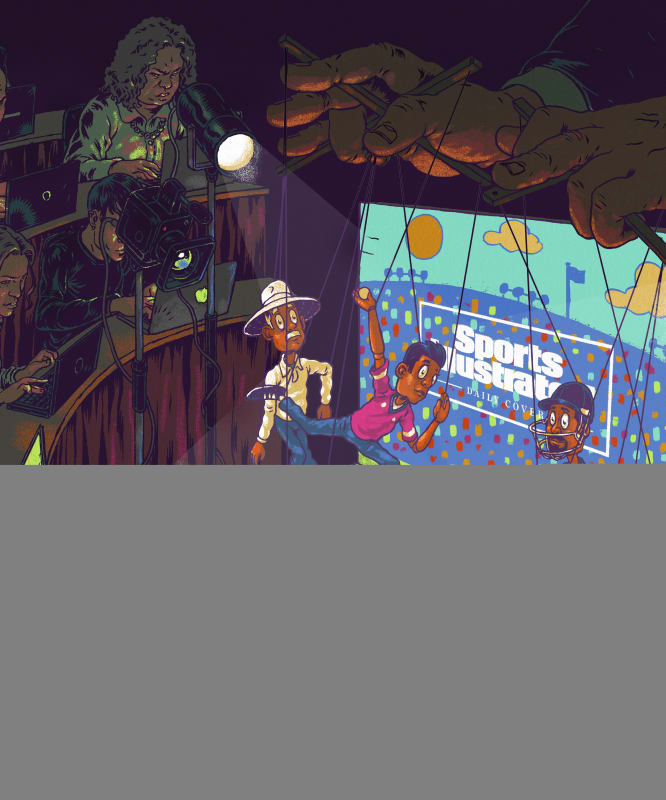

But when they retook the field for the second game, things got strange. Sometimes a batter swung and missed but one of the two on-field umpires, after consulting his walkie-talkie, would raise both hands to signal a six, the cricket version of a home run. Other times the official told a bowler to loop the ball slowly, so it could more easily be dispatched into the long grass beyond the field’s spray-painted boundary line. “We didn’t like it,” Thakur told me. “I was made the captain, but I never took part in any decision.”

As the games progressed, the players largely figured out what was unfolding around them. None of them were permitted near the scorer’s hut, though, whence emanated a voice eerily similar to that of Harsha Bhogle’s, India’s most famous cricket play-by-play commentator and pundit. Had they peeked through its tin-snipped viewing hatch, they’d have seen the nerve center of a wildly elaborate scam. As police reports described it, Davda, Saifi and a third man named Rishabh Jain were huddled inside, streaming games to a YouTube channel named CenturyHittersT20 and inputting scores to a ticker site. They focused the camera tightly around the 22-yard strip between bowler and batter, ensuring that, once hit, a ball’s destiny was revealed to viewers only via the hand signals of Davda’s handpicked umpires and the play-by-play calls from Saifi, the skilled Bhogle impressionist.

The umpires received their orders from the hut via walkie-talkie—after the hut had received them from a Russian who called himself Misha and whose instructions, via the encrypted messaging app Telegram, flashed up on one of the LED screens. Bets from Russian punters rolled in on the other screen. “You want to win Punjab Giants?” asked the hut in one typical exchange, referencing one of Davda’s counterfeit teams. “No,” replied Misha. “Ahmedabad Tuskers.”

Despite the secrecy, anybody could tell the games were a fix. Nonetheless, some 50 villagers showed up daily to enjoy Davda’s ballyhoo and cheer on their boys. The league also attracted a group of a dozen men nobody knew—out-of-towners who sat on the boundary, checking their phones and paying close attention to the action.

By mid-morning June 16, nine days into the sham, Thakur was playing in a “quarterfinal” when an opposing batter thumped the ball into the bushes. When Thakur ran to fetch it, the strange men got up and began sprinting onto the field. Thakur’s first instinct was to crouch and hide in the overgrow—but he saw that only one man, Davda, was attempting to escape. Thakur stood up, and one of the men approached him. “There’s no need to get the ball,” he said. He was a cop.

The officers seized the equipment and hauled all 22 players to a station in the nearby city of Mehsana. They gave statements, and the police let them go. No such fate awaited Davda, Saifi, Jain and the two umpires. Officials hit them all with conspiracy charges carrying a maximum prison term of seven years. They were released on bail after two days. (Efforts to reach both umpires and most of the players were unsuccessful.)

It took around a month for local media to break the news of the plucky villagers who’d built a league from nothing and rigged games to put one over on Russian bettors—a plot ripped, it seemed, right from the pages of a Bollywood script. Headlines soon blared across the globe. In Great Britain, The Guardian noted how the “scheme has echoes of The Sting”—the 1973 Paul Newman and Robert Redford movie in which con men organize a fake betting parlor to scam a mob boss.

Cops at the time claimed the scheme had raked in a total of $4,300, a small figure to American ears but big-time dollars in Molipur. Cricket stars chimed in on social media, as did the real Bhogle. “Can’t stop laughing,” he tweeted.

But something much bigger was going on. And it wasn’t a comedy at all.

Illustration by Andrew DeGraff

When businessman Lalit Modi (no relation to the prime minister) conceived the IPL, in 2007, cricket “purists” queued up to ridicule the concept. “Test cricket is like a single malt scotch because you remember every sip,” said historian Ramachandra Guha in 2016. “All that you remember after a T20 is that you got smashed.”

But cricket fans couldn’t resist a cheap drink—and Modi’s creation, with showy touches like flamethrowers, cheerleaders and VIP boxes stuffed with stars of Bollywood and big industry, dripped with tamasha, an Indian word meaning at once glamour, fun and high drama. Today the IPL’s media-rights deal pays more per match than any league except the NFL. Where Indian cricket was once dominated by the merchant classes of four former-colonial strongholds—Mumbai, New Delhi, Kolkata and Chennai—it has now spread to less-gilded outposts, offering superstardom to slumdogs. “The IPL is a story of modern India,” broadcaster Boria Majumdar say—“that everyone can aspire to be rich and prosperous.”

It is a source of huge pride, therefore, that, in the IPL, India has a world-

beating entertainment product—not least in a sport foisted upon it by invading Redcoats (it is lost on few that, now, the best English cricketers come to India to play in the sport’s top league). But the IPL has inherited the corruption that plagued the “gentleman’s game” long before Lalit Modi came along. Gambling and cricket have coexisted for almost three centuries—English aristocrats drew up the first official rules of the game in 1744 with the express purpose of settling betting disputes—and bookies have flooded the sport with dark money ever since. In 2000, gangsters persuaded the captains of India and South Africa to throw Test matches. Ten years later, English police jailed three Pakistani stars and a bookie for participation in a fixing scandal.

Early IPL franchise owners were a rogue’s gallery of con men, carpetbaggers and scoundrels—none worse than Lalit Modi himself, a splashy Duke-educated businessman with prior convictions for cocaine possession, kidnapping and assault. In 2013, after Indian cricket authorities banned him for offenses including rigging bids in the auction of two franchises and selling media rights without authorization, he fled to London. That same year, an IPL betting scandal ended the careers of a star Indian bowler and a team owner.

Barely a season has passed since without accusations of IPL match fixing. Twenty years ago, before the IPL, a top-level Indian domestic player earned between $25 and $75 per match. Mobsters could seduce a player to throw games with a few thousand bucks. The IPL’s highest earner in 2023, England’s Sam Curran, made $2.26 million for last season’s 14 matches. That type of pay, the league’s organizers say, makes it tougher for criminals to get a foothold in dressing rooms.

At the same time, the IPL’s popularity means that people gamble on it from London to Lahore, swelling the rewards for would-be fixers. And while gambling in most forms has been illegal in India since colonialism, the proliferation of digital sportsbooks has allowed Indian bettors to satisfy their compulsions with a tap of their smartphones.

Betting sites offer digital storefronts in the country while basing operations overseas, making prosecution nearly impossible and contributing to an Indian illegal sports betting market now worth up to $150 billion. Even lower divisions and charity games can be targeted for manipulation. “So many things are happening which we still don’t have a grip on,” says Chandramohan Puppala, the author of a 2019 book on match-fixing called No Ball. “Or even if we know, we don’t know how to catch them.”

One investigator in Ahmedabad who asked not to be named told me that he’d busted two underground gambling rings worth $170 million and $85 million this year alone. Beneficiaries include politicians and even fellow cops, he added, which dampens the appetite for both regulation and investigation. “If you start working too diligently,” he says, “you’ll be harassed by your superiors.”

The IPL, then, isn’t simply the tamasha-soaked talisman of modern India. For many it’s also a potential golden ticket, whether they’re holding a bat or a betting stub. As his country left him and his village behind, the question for Shoeb Davda was a simple one: Why shouldn’t cricket be his golden ticket, too?

Illustration by Andrew DeGraff

In early 2020, Davda was in deep trouble. His bangle store was failing. So he borrowed almost $22,000 from the bank to purchase a local cowshed and a herd of cattle. It seemed like a safe bet.

Then COVID-19 hit. Industry in Molipur grinded to a halt, and Davda couldn’t get his cattle business off the ground. The bank wanted its cash back—and he couldn’t pay. A friend told Davda he could make good money working illegally in a European country called Malta. But he couldn’t fly there direct. Instead, the friend said, Davda would travel to Moscow, where Russians would hook him up with a Maltese visa. In January 2022 he boarded a plane to the Russian capital, where he met a man he knew via Telegram only as Misha.

Davda never made it to Malta. Instead, Misha dispatched him to a suburban Moscow factory. Davda says he boxed toys in one half of the building by day and slept in the other half alongside South Asian men by night. “I was confined,” he told me when we spoke this spring on the stoop of his shuttered store. “I didn’t see life outside.”

Slight with a soft belly, Davda wasn’t built for heavy lifting. So when a couple of weeks later he was offered the chance to play indoor cricket for the equivalent of $700 a month, he leaped at the chance. Each day for six weeks thereafter, Davda played between five and eight 10-overs-per-side games in a bare-walled Moscow sports hall. There seemed to be some kind of league structure, but Davda couldn’t fathom it. He knew something was fishy, though. Russians didn’t know cricket. And by Davda’s own admission, he wasn’t much good at playing it. He was no athlete, with poor eyesight and bottle-top glasses. Which made the Moscow setup even stranger: There were high-end equipment and cameras that—as Davda learned—were livestreaming each match to a local betting website.

When he returned to Molipur two months later, it was Misha—and, according to police reports, two Russia-based Pakistani men named Majid Khan and Mohammed Asif—who put Davda up to building his league. (Efforts to reach Khan failed. During a brief phone call, Asif denied any involvement.) If Davda could do it, Misha said, he’d pay him back for the gear, plus a $1,200 monthly stipend. To help, Misha would send Saifi and two Indian men who, like Davda, had played cricket in Russia: Jain and Ashok Chaudhary. Chaudhary had recently tried—and failed—to establish a similar league hundreds of miles away in Meerut. (Chaudhary says that monkeys kept chewing through electrical cables, among other issues.) Police reports claim a Moscow-based grocer, Gurmeet Singh, then wired Davda an additional $5,000 via informal lenders called angadias. (Singh refused to speak for this story.) Davda, dutifully, got to work.

“If I knew it was going to be a betting racket,” Davda told me coyly, “I would not have gotten involved.” That level of ignorance was hard to believe, I replied. But his plight was clear. He was dealing with powerful forces in Russia. In fact, it sounded like Davda had been trafficked into Russia, I told him. Silence. “He won’t answer that question,” my translator said.

The cops had identified Davda as the mastermind of the Molipur cricket scam—and that’s how he had been portrayed in global media. As he told his story, standing on the stoop of the bangle store, the notion that Davda was a criminal mastermind evaporated quicker than a lassi in the Gujurat sun. If anything, he was one of the tens of thousands of victims of human trafficking from India each year—of which Gujarat is a key source. What happened in Molipur was clearly being directed by Davda’s former captors. But Davda refused to elaborate on Misha.

Who was he? The officers in Mehsana admitted they hadn’t even tried calling him, instead lodging a request for cooperation with Russian authorities they knew would be ignored. One thing was clear: Misha was part of something much bigger than Molipur.

Illustration by Andrew DeGraff

On June 22, a 42-year-old former Russian intelligence agent named Sergey Karshkov visited a Zürich clinic for a routine MRI scan. He suffered an allergic reaction to the scan’s contrast fluid, fell into a coma and died. “It just can’t be,” his friend Pavel Muntyan posted to Facebook. “Sergey was one of the most athletic and healthy people I knew.”

The FDA records a death rate of .00008% for such events, few of which occur in elite facilities like the one in Zürich. Some have grouped Karshkov with the 38 prominent Russian tycoons and critics of Vladimir Putin who’ve died in suspicious circumstances since Moscow invaded Ukraine last year. But if the Ukrainian-born Karshkov’s death was shrouded in mystery, it mirrored the company he cofounded in 2007: 1xBet.

1xBet is probably the biggest sportsbook on the planet—but it isn’t allowed to operate in the U.S., the U.K. or a host of other Western nations. Founded in Russia, licensed on the Caribbean island of Curaçao and headquartered in the Cypriot city of Limassol, its revenue is unknown. An investigation by the Dutch publication Follow the Money recently tracked $4 billion flowing through 1xBet cryptocurrency accounts, indicating that tens of billions of dollars likely move through the site annually. Even as authorities have banned it in countries like Spain and France, it has signed lucrative global endorsement deals with those countries’ biggest soccer clubs, including FC Barcelona and Paris Saint-Germain.

Russia banned 1xBet in 2014 for avoiding taxes, and Karshkov moved the firm to Cyprus. But 1xBet continued operating in its home nation under the spin-off sites 1XStavka.com and 1XBit.com (for Bitcoin transactions) while signing a $5.5 million sponsorship deal with the state-backed soccer club Dynamo Moscow. Around the globe it has flouted bans for almost every betting infraction possible: from copyright violations, stealing deposits and marketing to minors, to offering odds on cockfights and even children’s sports. To date around 1,800 1xBet-affiliated sites appear on regulatory blacklists worldwide.

1xBet’s remaining cofounders, Roman Semiokhin and Dmitry Kazorin, are wanted by Russian law enforcement. So are other figures associated with the company, for an array of charges, including drug trafficking. With its links to the Russian intelligence and criminal worlds, the true nature of the sprawling 1xBet network is only vaguely understood. Its relationship with the Russian regime is similarly mysterious: Russia bans the service and labels the founders as wanted criminals but allows its knockoff sites and blesses it with sponsorship dollars from a state-owned club.

The firm’s leaders live in open luxury in Limassol, alongside around 400 employees. 1xBet parks revenue in tax havens in Curaçao, Gibraltar, Liechtenstein and likely elsewhere.

According to Russian media, authorities in that country have accused at least one close associate of 1xBet of money laundering. In fact, digital sportsbooks, especially loosely regulated ones like 1xBet, are known as hubs for the activity. The 20th-century casino boom meant crooks could exchange huge sums for chips before converting their winnings into clean cash—minus, of course, the house’s cut. Digital sportsbooks are an even more profitable money-laundering method, according to Ronan Lorcan O’Laoire, a sports crime and corruption expert at the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. In “classic money laundering,” he says, “you probably need to invest 20 to 25% of the funds you’ve collected illegally to buy a restaurant, buy a hotel, buy a property—then you hope of course that it increases in value.” By fixing contests on betting sites, however, the down payment is far smaller. “You pay off the referee or you pay off the players, a few thousand or whatever,” says O’Laoire. “You can guarantee the result.”

1xBet has focused primarily on developing markets in Africa, South America and, perhaps the biggest opportunity of all: India. The country’s booming betting market and “free-for-all” regulation, as Philippe Auclair, a U.K.-based journalist who has followed 1xBet for years, describes it, has made cricket the focus of an extraordinarily aggressive marketing campaign by the site. It has plastered its Indian brand name, 1XBat, across billboards, broadcasts and boundary hoardings nationwide. On 1XBat.com, Indian fans can find all manner of cricket content—with, of course, links that shuffle them over to 1xBet (never itself advertised in the country), where they can place their wagers.

Soon after visiting Molipur, I reached Misha via Telegram—only he claims his name is not Misha; it’s Andrey (he declined to share a last name), and he says he’s a broadcast engineer for 1xBet in Yaroslavl, a city 170 miles northeast of Moscow. In fact, he told me when we first spoke, he was streaming an indoor cricket match right at that moment—and sent me screenshots of something that looked a lot like the games Davda described participating in while in Russia.

Andrey directed me to the “live” section of 1xBet’s homepage. There were not only odds on mundane pastimes like table football and marble runs, but also a slew of strange team contests, streamed from spectatorless halls, featuring players with little or no ability competing with the intensity of a suburban aquarobics class. Andrey isn’t sure how many matches are held each week, he told me, “but they seem to be playing around the clock.”

Davda’s Molipur cricket league was not a one-off caper, it turns out. It was a single node in a network of at least dozens of Molipur-style scams worldwide.

Soccer, hockey, basketball, handball and, of course, cricket feature in these dark corners. The investigative website Josimar, for which Auclair writes, has geolocated many to halls across the former Soviet Union. I’ve watched the “Banaras T10” league, the “Area Cricket League” and the “Akluj Rural Championship,” a showdown filmed at an Indian park, with the camera focused tightly on players in tattered polo shirts and using ancient equipment—a dollar-store version of Molipur’s IPL. Streaming one of its matches I noted six moments that were clearly fixed.

Why target players to fix legitimate tournaments when you can simply create a tournament from scratch and fix it yourself? Investigative journalist Steve Menary told me he has heard conversations about bets of $5 million being placed on such ghost events. “Regular betting sites don’t want to be ripped off,” he said. “Whereas 1xBet, they’re money laundering because the criminals own the bookmaker.”

A 1xBet spokesperson told me over the phone that all games hosted on the site are fair. Asked how each game’s integrity is ensured, he replied, “This is internal information, how they’re being checked and how they’re being verified. I’m unable to provide you with this exact information.” He declined to answer further questions and hung up.

Soon afterward, I contacted an official at Russia’s cricket association, who, fearful of reprisal, requested anonymity to discuss how difficult it’s become to promote an honest version of the sport in his country. He acknowledged that South Asian men are commonly trafficked into Russia to play in what he called, euphemistically, “hanky-panky” cricket leagues and said he suspects the practice exists more widely in Europe. The true scale of the problem remains unknown.

To demonstrate the ease of creating such a hanky-panky league, the official directed me to a Russia-based fixer I will call Zaheer. Posing as a British businessman looking to establish a fixed, indoor cricket league, I was informed there were two kinds: Moscow and Yaroslavl, the latter of which was not just the Russian city in which Misha (or Andrey) said he was based, but also a shorthand for 1xBet’s fixed events. “If you want this kind of good, natural game, it will be one option,” he told me. “If you need like Yaroslavl . . . then it will be another option.”

Getting players would be no problem, Zaheer added. “I am giving them visa—like a student,” he said. “They are not students, but I can enter them in some universities, and they can play.”

But if such events may already launder millions of dollars, why build Shoeb Davda’s fake IPL? Why go to the trouble of the field and the crowd noise and the announcer and the lights?

Davda wouldn’t tell me, nor would Andrey give me the names of his higher-ups—though he said they were three people “from the Yaroslavl branch of 1xBet.” But the key seemed to be in that $150 billion Indian black market. Perhaps Molipur was an attempt not only to clean dirty money but also to attract the millions of Indians who’ve gotten into betting off the back of the real IPL? Cricket fans recognize the majority of 1xBet’s live events as “absolute crap,” Menary told me. Make something that looks enough like the real thing, he added, and some could be tempted to part with their cash.

While at least one other league got off the ground in India, similar events have faltered—not least the one attempted in Meerut by Davda’s accomplice Chaudhary. It was Davda’s industriousness, therefore, that ensured his downfall. But the cops in Mehsana failed to call a single alleged conspirator outside India. The latest word from my translator, back in Gujarat, is that, according to a police source, the charges are likely to be dropped.

For 1xBet and its Russian and Indian organizers, the whole affair appears likely to end as a wash: little gain but no known repercussions. The game was fixed, and it was the poor who got stung the hardest. The players in Molipur told me they’d never been paid, and most left the village when the scam went viral. Sanjay Thakur’s father gave him a beating. “I don’t want to play cricket anymore,” he told me.

Davda fled Molipur for two months after the raid, turning down multiple requests for interviews and even a lucrative documentary deal—despite his financial plight. He has since returned and told me I was the first reporter he’d spoken to. “I never expected such a thing would happen to me,” he said softly. “I’d never visited a police station. This is a zero-crime village.”

He still enjoys watching the IPL on TV, he told me—albeit less often than he once had. A pack of stray dogs howled in an alley a few yards away. Davda flinched. He’d barely clawed back any of his expenses, and the Russians never gave him the payout they’d promised.

He told me he was the scam’s true victim. “I have the feeling I’ve been cheated,” he said. “Duped.”