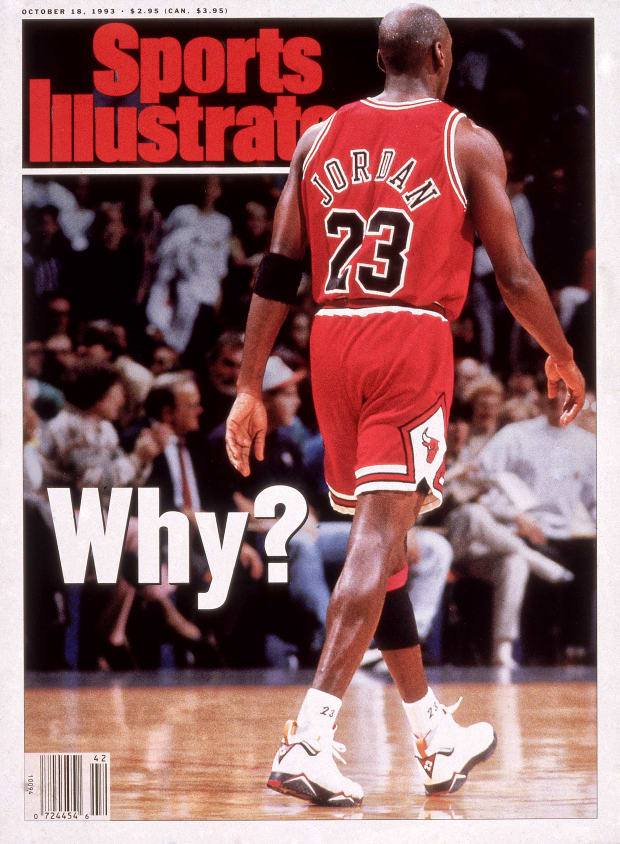

Michael Jordan’s first retirement from the NBA has led to conspiracy theories over the years to explain why he left the Chicago Bulls in October 1993.

While most of The Last Dance’s commentary on Michael Jordan is flattering, Jordan’s career featured several controversies that will be explored in upcoming episodes. One was his shocking decision to retire from the NBA in October 1993.

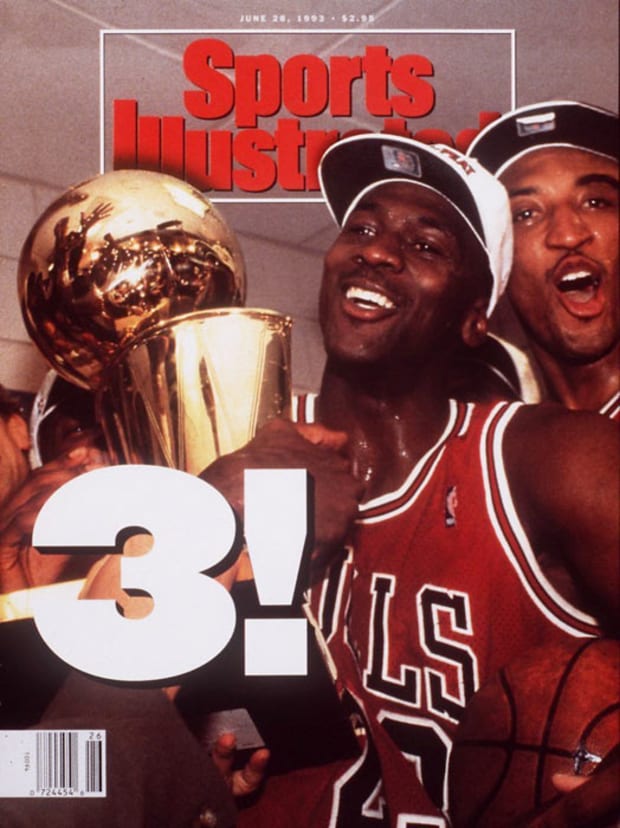

Jordan was only 30 years old at time. He was healthy and seemed to be at his professional peak. Four months earlier the Bulls had won their third-straight title. The former UNC star and Olympic Gold medalist had led the league in scoring for the seventh straight season and been named the 1993 Finals most valuable player. But life was hardly perfect. Over the summer, Jordan had experienced personal tragedy with the murder of his father, James Jordan, Sr.

In a nationally-televised press conference held at the Bulls’ practice facility, Jordan stunned the basketball world by retiring. “The desire isn’t there,” Jordan explained. He felt there wasn’t “anything else to prove.”

Later years would “prove” otherwise. After batting just .202 for the Double-A Birmingham Barons in 1994, Jordan returned to the NBA in March 1995. He went on to win three straight titles, retire two additional times (1999 and 2003), and demonstrate, once again, that he was the GOAT.

But the 1993 retirement struck many as confounding.

Over the years, there’s been speculation that Jordan’s decision was less of a choice and more his end of a tacit agreement with the NBA. As the (uncorroborated) theory goes, the NBA was concerned about Jordan’s gambling ties and wanted him to take a break. Jordan “voluntarily” stepping away would serve as a face-saving measure for all involved. Perhaps the league didn’t want to publicly punish Jordan—the most marketable athlete in American history—and give fans a reason to question their loyalty to the NBA. Jordan, who earned approximately $30 million a year in endorsements during the early ’90s, was likewise invested in avoiding irreparable harm to his brand.

The gambling theory wasn’t entirely out of thin air. Jordan had recently been seen playing blackjack at an Atlantic City casino the night before a Bulls playoff game against the New York Knicks. He had also admitted to incurring substantial losses from gambling. Earlier in 1993, the NBA appointed Frederick Lacey, a former federal judge and U.S. attorney, to examine whether Jordan’s gambling ran afoul of league rules.

Gambling, provided it complies with the law, is not automatically prohibited by league policy. While state laws vary on permissible forms of gambling, there are numerous ways to gamble within the confines of most states’ laws. This is generally true of lotteries, scratch tickets, card games and slot machines.

The problem for an NBA player is if his gambling relates in any way to the league’s games. Specifically, under Article 35(f) of the league constitution, “any player who, directly or indirectly, wagers money or anything of value on the outcome of any game played by a team in the NBA” is subject to a fine, suspension or expulsion. This portion of the league constitution is expressed in players’ contracts and is incorporated by reference in the league’s collective bargaining agreement with the National Basketball Players’ Association.

Writing in Sports Illustrated in 1993, Jack McCallum detailed how there were “two gambling-related Jordan bombshells” that drew NBA scrutiny: “The first came in late 1991, when a $57,000 check from Jordan was discovered by the IRS in the bank account of convicted cocaine trafficker James (Slim) Bouler; then $108,000 in checks from Jordan were found in the briefcase of slain bail bondsman Eddie Dow.”

To put it charitably, Jordan had misrepresented the nature of his gambling activity and debts. As McCallum details, Jordan originally claimed that he had loaned money to Bouler only to later admit the money was to extinguish a gambling debt. Jordan also neglected to mention to Lacey—a former federal judge—that he had incurred substantial gambling debts to his golfing partner, Richard Esquinas.

Jordan only added fuel to the fire during his farewell press conference. It came in his response to a journalist’s hypothetical question about whether Jordan considered the possibility that, after a year away, he’d miss the game more than he anticipated and would want to come back. Jordan responded that while he was “pretty sure” he would miss the NBA, “to come back would be different.” But Jordan stressed that he was “not making this a never issue” and suggested “five years down the line, if that urge comes back, if the Bulls have me, if David Stern lets me back in the league, I may come back.” If you’re interested in watching how Jordan appeared when he made these remarks, jump to 45:13:

There is one sequence within his remarks that jumps out: “if David Stern lets me back in the league.” Those words were likely a gracious nod of deference to the commissioner and his authority. Still, if we take Jordan literally, his choice of words invited suspicion. Why would he need the commissioner’s permission to re-join the league?

Context matters, too. The early 1990s was a very different time in America. Gambling, and particularly sports gambling, was often viewed with apprehension and as linked to a nefarious underworld. The Pete Rose scandal was fresh on everyone’s mind. As manager of the Cincinnati Reds, Rose had bet thousands of dollars on Major League Baseball games during the 1980s. Rose’s bets damaged the integrity of the game and called into question whether his in-game decisions were motivated by wagers instead of competitiveness or strategy. He was banned for life from MLB in 1989.

The Rose scandal wasn’t the first to undermine confidence in sports. In 1983, NFL commissioner Pete Rozelle suspended Baltimore Colts quarterback Art Schlichter after he was found to have bet on at least 10 games during the 1982 season. Four years earlier, Boston College basketball players were implicated in a point shaving conspiracy.

As a result of lobbying by the major pro leagues in the early ’90s, Congress passed and President George H.W. Bush signed the Professional and Amateur Sports Protection Act of 1992 (PASPA) into law. PASPA made it illegal for 46 states to authorize sports betting. Four states—Nevada, Delaware, Oregon and Montana—were exempt on account of those states having already adopted sports betting practices. This highlighted how PASPA wasn’t designed to take sports betting away from states but only prevent additional states from legalizing it. Yet as to the leagues, it was clear they were concerned about gambling and its influence on their sports.

These factors all gave reason to wonder if there was more to Jordan’s retirement than him feeling burnt out.

Debunking the conspiracy

Conspiracy theories can be engaging but are sometimes devoid of confirmable facts. With that in mind, there are at least seven reasons to doubt that Jordan’s retirement was directed or encouraged by the NBA.

First, the intensely competitive Jordan offered a number of plausible rationales for why he wished to retire. He felt drained and didn’t see there was much else to prove. As noted earlier, Jordan’s father had also recently been murdered, which no doubt took a toll on Jordan. Sometimes what people say is what they feel.

Second, Stern flatly rejected the idea of the NBA pushing Jordan out. “As far as the NBA is concerned,” Stern said, “Michael Jordan did nothing wrong, and I resent any implications to the contrary.” Stern further told McCallum that he was certain Jordan never had a gambling addiction and never bet on NBA games. Stern shared these sentiments despite Jordan’s lack of candor with Lacey. The NBA closed its investigation into Jordan two days after his retirement.

Third, Jordan’s retirement happened 27 years ago and, to date, no evidence has surfaced that proves there was a connection. Books have been written about Jordan and none has substantiated the conspiracy. Just the opposite, Jordan’s stated reasons—that he wanted a break—seem consistent with him feeling rejuvenated when he returned.

Fourth, the notion that the NBA would want Jordan to step away from the game defies logic. Jordan is the most marketable player in league history. No one is more responsible for the league’s transformation from having playoff games broadcast on tape delay as late as 1986 to an enterprise that generates billions of dollars a year in TV revenue. Jordan was only 30 years old when he retired in 1993. Seemingly the last thing the NBA wanted was for the face of the sport to step away. The NBA without Jordan was weakened, including for purposes of negotiating TV, merchandise and apparel contracts.

Fifth, if the NBA wished to punish Jordan, there were collectively bargained measures available. The NBA could have warned, fined or suspended Jordan for conduct detrimental to the league. There was no need for a secret pact for Jordan to step aside. The league could have reached the same outcome without inviting the attention of conspiracy theorists.

Sixth, the NBA doesn’t operate through cloak-and-dagger compacts or by way of winks and nods. From Stern to Adam Silver, along with their top advisors, the league is run mainly by a group of highly skilled attorneys. If nothing else, attorneys tend to care deeply about process, procedure and consistency. An unprecedented informal arrangement, particularly between the two most important people in the NBA at the time (Jordan and Stern), would have sharply belied how attorneys normally operate.

Seventh, NBA owners, through the Board of Governors, unanimously approved Jordan as principal owner of the Charlotte Hornets (then called the Bobcats) in 2010. Four years earlier, Jordan—who in 2005 admitted to 60 Minutes’ Ed Bradley that he was at times reckless with gambling—was also approved to purchase a minority stake in the franchise when it was owned by Robert Johnson. Prospective franchise owners go through substantial review of their financial, personal and business dealings before they are approved. If the league had meaningful worries about Jordan’s gambling, it would have dissuaded him from pursuing ownership of a team. The opposite occurred: the NBA welcomed Jordan with open arms.

Times have changed

Nearly three decades after Jordan’s first retirement, NBA players (as well as owners, coaches, staff, referees) remain obligated to follow league restrictions on wagering activities. Along the way there have been key developments. In 2007, the league endured a painful wagering scandal. Referee Tim Donaghy was implicated in a scheme that involved using in-game foul calls to manipulate total points. The league learned from the Donaghy scandal. It became more vigilant in studying point discrepancies that could indicate the presence of an improper plot.

At the same, the NBA has gradually embraced the industry of sports betting. This is true despite the league joining the NFL, NHL, MLB, NCAA and the U.S. Justice Department in an unsuccessful effort to limit the number of states with legal sports betting. In the early 2010s, this group pursued federal litigation to block New Jersey from legalizing sports betting in contravention of PASPA. Yet in 2014, Silver penned an op-ed for The New York Times in which he argued the federal government should allow states to legalize sports betting so long those states adopt safeguards.

Congress didn’t heed Silver’s advice, but the U.S. Supreme Court entered the story in a big way. In 2018, the Court ruled in Murphy v. NCAA that PASPA was unconstitutional. The ruling paved the way for states to legalize sports betting. So far, 17 states have done so. Others will soon join them.

Since 2018, the NBA has increased its business ties to the gaming and wagering industries. It’s done so by, among other steps, signing a multi-year partnership with the Las Vegas-based MGM Resorts to make it the official gaming partner of the NBA and WNBA. The league has also landed betting data partnership agreements with Sportradar and Genius Sports. These deals will lead to new revenue streams for the NBA, particularly once games resume after the coronavirus disease pandemic passes. The deals will also provide NBA owners, including Jordan, with more revenue. Jordan always seems to win.

Michael McCann is SI’s Legal Analyst. He is also an attorney and Founding Director of the Sports and Entertainment Law Institute at UNH Franklin Pierce School of Law.