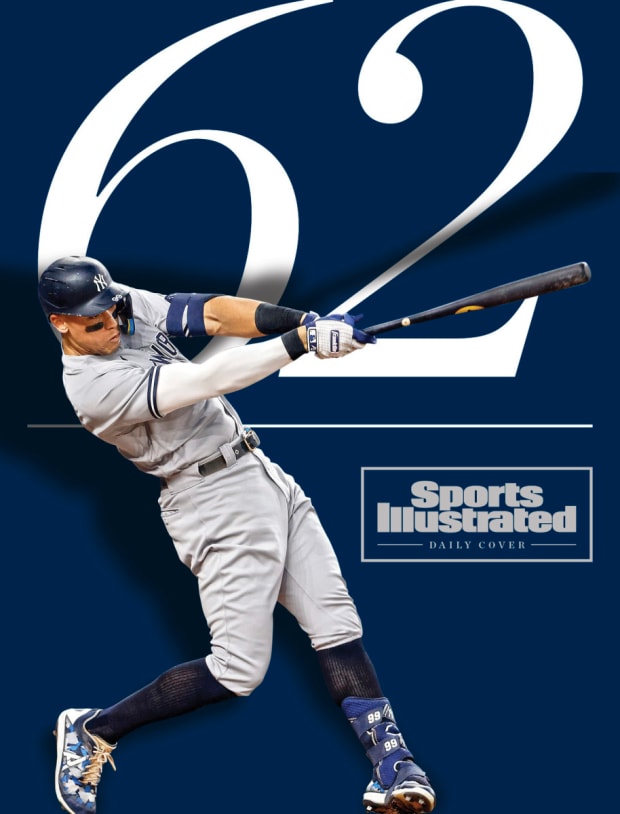

The Yankees’ slugger was under pressure all season, but the American League home run record had nothing to do with it.

As everything changed around him—the baseball itself, specially switched out so the league could authenticate it more easily; the crowd reaction, soaring to a gasping, echoing roar that made Globe Life Field sound almost like Yankee Stadium; and the American League home run record, which after 61 years is no longer 61 but 62—Aaron Judge stayed the same.

After it was over and the Yankees had enjoyed what must be the most joyful loss, 3–2, in franchise history, he told reporters that he was excited, largely because he gave his team a 1–0 lead over the Rangers. But he was also relieved.

“As the leadoff guy, I gotta get on base, and I hadn’t been doing that,” said the AL single-season home run king, adding that he tries to be “a table-setter.”

Ron Jenkins/Getty Images

This is a man who hit his 60th home run of the season two weeks ago and berated himself as it flew for not doing it a few innings earlier, when there were men on base. He added that as his attempt to chase down Roger Maris for the AL crown dragged into the season’s final days, as he walked and singled and doubled but failed to homer, he worried that he was letting his teammates and fans down. Judge said he was glad “everyone can finally sit down in their seats and watch the ballgame.”

If this is an act, Judge has been committed to it for at least a decade. When he attended Fresno State, the Bulldogs’ baseball team enforced a rule: Anyone who used I or me boastfully had to pay a fine. In three years there before the Yankees took him in the first round of the 2013 draft, Judge never slipped up.

So let him deflect. His teammates understood the significance of the moment. They were perched at the dugout rail, willing him on, as they had been for weeks. (“Every fly ball, we’re screaming with the fans,” lefty Nestor Cortes Jr. said recently.) They coiled as Texas righty Jesús Tinoco hung a slider. They exploded onto the field as Judge walloped it to left field. They gathered at home plate to wait for him, offering hugs and handshakes and high fives when he jogged past them.

“It was emotional for all of us,” ace Gerrit Cole told the YES Network afterward. “There were some watery eyes out there.” (Cole set a record, too; his 257 strikeouts are the most by a Yankee in a single season. How will he celebrate? “I just want to hang out with Aaron, really,” he said.)

The fans went nuts, too, cheering Judge as if he were one of their own. They knew what a tremendous season he has had. They knew how gracefully he had handled the attention. They probably did not know that shortly before the game, Judge had texted his personal hitting coach: He believed he had identified a problem with his swing.

LM Otero/AP

Judge, 30, has a chance at something we might call the Decuple Crown: He leads the league not only in home runs (perhaps you’ve heard) and runs batted in (131), but also in wins above replacement (10.7), on-base percentage (.425), slugging percentage (.686), OPS (1.111), runs scored (133), walks (111) and total bases (391), and he could overtake the Twins’ Luis Arraez on Wednesday for batting average (Judge sits in second at .311).

Perhaps the most impressive aspect of Judge’s performance is the environment in which he is accomplishing it. Pitching is more devastating than it has ever been, the baseballs themselves seem to fly less far this year than in the past few seasons, and the league tests for performance-enhancing drugs. Fly balls have not left the park less often since 2012.

“He’s doing it in an era that is very tough to hit. Let’s put it that way. I’ll leave it at that,” Red Sox manager Alex Cora, who played when Barry Bonds, Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa were jockeying for the lead in the late 1990s and early 2000s, told reporters last month. “The separation between him and the rest of the players is huge.”

Indeed, according to research painstakingly compiled by the great Alex Speier of The Boston Globe, no man since integration has ever enjoyed such a large home run lead over second place. In the history of the sport, the average dinger king has beaten the runner-up by 13%. Judge is ahead by 35%, a gap “as colossal as Judge himself,” as Speier put it.

At one point, it looked as if Judge might have an outside chance at 74 longballs, which would break Bonds’s overall single-season home run record. He hit Nos. 58, 59 and 60 in a two-game stretch, meaning he would have needed 14 dingers in 15 games—an outrageous task that started to seem doable for someone as locked in as Judge.

But none of the Yankees’ other regulars are hitting even .265, and as the AL record approached, opposing pitchers seemed reluctant to let Judge beat them. He began seeing one, maybe two competitive pitches per night. He often lined them for singles and doubles, providing the odd tableau of a home crowd groaning at its own player’s success. “I was getting booed for a single!” he said Tuesday.

In the 13 games after he hit No. 60, Judge had a .231 batting average—and a .483 OBP. He hit one home run.

Tony Gutierrez/AP

Through it all, people asked him whether the pressure had gotten to him. It was all he could do not to laugh.

Pressure? He began the season by refusing a seven-year contract extension worth $213.5 million, listening as general manager Brian Cashman released the proposed terms to the media and pretending not to listen as the crowd jeered him.

Pressure? The Yankees, who woke up on June 19 on pace to win 122 games, went 24–32 over the next two months, as seemingly every person who ever wore pinstripes found his way onto the injured list. Judge slugged .656 during that stretch, probably single-handedly saving the jobs of his manager and a hitting coach or two. At times, first baseman Anthony Rizzo would turn to Judge in the dugout and say, sort of joking but sort of not, If you don’t do something tonight, we’re screwed.

Pressure? Judge acknowledged that being linked to Maris and Babe Ruth, who held the record before him, is “something pretty special,” but he believes that 73 is the home run record. So no, he told Sports Illustrated last week, the pressure of hitting 62 never got to him.

“For me, it’s just another day,” he said. “I was getting booed in April [in the Bronx] after turning down the deal. I had fans yelling at me, screaming at me, saying, ‘You should’ve taken the deal! What are you doing? Screw you!’ So this is just another day.”

Judge has carried that mindset all season: Today is just another day. He has always loved routine—loved not knowing what day of the week it is, loved measuring time only in series, loved focusing on the task immediately in front of him—and amid the upheaval of this season, he has craved that comfort.

“I eat at the same spots,” he said. “I do the same thing. For me, it kind of simplifies everything, so I don’t have to worry about a lot of unknown. I like making sure I’m prepared for any situation. So for me, through this whole process—the contract talks, trying to win our division, the home run record, anything—I just try to keep the status quo.”

That meant getting ahead of potential problems. After his disastrous 2016 debut, in which he hit .179 with 42 strikeouts and nine walks in 95 plate appearances, his agent, David Matranga, introduced him to Richard Schenck, a private hitting coach who stresses the idea that a hitter should first move the bat not forward but backward.

“What the great hitters do is they create a stretch in their body that is different than everybody else,” Schenck says. “Everybody else uses the momentum of their forward move to generate force. And all the great hitters are stretch hitters. They counter that forward move with a coil of their hip and a pull back of their back muscles, and so they end up with a stretch like pulling the rubber band back of a slingshot. And then when they launch the bat rearward, their rear leg suddenly explodes out of that stretch. And that’s where the quickness comes from. That’s how they get the barrel to the ball so quickly.”

Watch MLB live with fuboTV: Start a free trial today!

The idea may seem counterintuitive, but it made sense to Judge, especially when the sexagenarian Schenck beat him in hand quickness during drills. Judge overhauled his swing, led the league with 52 home runs in 2017 and won Rookie of the Year.

In the years since, Judge would call Schenck whenever his swing felt out of whack, and the coach would fly out for a tune-up. This year they decided to set a schedule instead. Every two weeks or so this season, either at home or on the road, Judge and Schenck met for a lesson. Schenck would rent out an entire facility—sometimes late at night; whenever they could get the time—so Judge could practice in private. Often he brought a Yankees teammate or two.

“The last couple [sessions] I have noticed an extreme confidence and peace,” says Schenck. “He knows what he's doing. He knows how to do it. It's just a matter of doing it.” The past few times, Schenck said, he even texted Judge: You look great. Are you sure you want me to come? Every time, Judge said: Yes.

Tony Gutierrez/AP

They last worked together in person on Sept. 20, the afternoon Judge hit home run No. 60. Since then, they have stayed in close touch, texting about Judge’s great hitting fear: “falling out of the phone booth.” His motion is most successful when it is at its most compact, as if he could complete it with his entire body inside a phone booth; at 6’7” and 282 pounds, he can easily let his swing get too long.

But on Tuesday his concern was different. He went 1-for-5 with a single in the first game of the doubleheader, then texted Schenck shortly before the second game: I think my direction is off. He felt he was launching the ball too far toward his pull side, or up the middle; he needed to aim for the opposite field. Schenck calls it “attacking oppo.” The idea is not necessarily to force yourself to hit the ball the other way. It’s about being on time.

“I could look at a hundred hitters in the league and somebody might try to break down their mechanics, but I could just tell you straight up, That guy wasn’t ready to hit,” Judge said last week. “They weren’t on time, they weren’t in position to hit by the time the ball was released, and that’s why they pulled off the ball. So for me, the first thing I check is always, Was I on time, ready to hit before he released the pitch? If I wasn’t ready to hit, how can I start breaking down my mechanics?”

On Tuesday, Schenck reminded Judge of a few cues to keep himself on time. A few minutes later, Judge strode to the batter’s box. He took a four-seamer well above the zone for ball one. He took a slider down the middle for strike one. He got nearly the same pitch again. He pulled his bat backward and hit the ball forward.

As he rounded the bases, he thought about his parents, Patty and Wayne, and his wife, Samantha Bracksieck, who have followed him for two weeks as he chased history. He thought about his teammates, who have stood shoulder to shoulder with him through the grind of the season. He thought about the fans, who have willed him to this mark. He will remember Tuesday night forever. It was nearly flawless, he said. He was just disappointed the team lost.

More MLB coverage:

• Aaron Judge: The Authentic Home Run King

• Everything in Aaron Judge’s Career Led Him to This Historic Season

• The Guardians Are MLB’s Most Interesting Playoff Team

• ‘Let’s F—ing Party’: The Mariners Finally End Their 21-Year Playoff Drought

• How Austin Riley Became the Cornerstone of the Braves’ Core