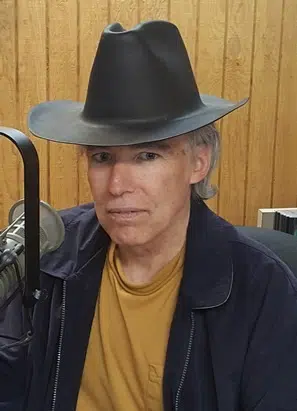

Josh Schertz’s goggles are fogging up. The coach of the Indiana State Sycamores is sitting at a postgame news conference in the Hulman Center in Terre Haute, Ind., rehashing a thrilling victory over the Bradley Braves, and he’s wearing goggles—which is odd, of course. Oddly endearing, which is the prevailing aura that has blossomed around this basketball team.

Anyway, Schertz is sitting there in front of the usual sparse media crowd after a wild overtime game in a raucous arena, and he’s got a set of fan giveaway goggles on his round face. Just like thousands of Indiana State backers in the building earlier that night, he’s honoring College Jokić, or Cream Abdul-Jabbar, or Larry Blurred—whatever nickname you prefer for his improbable star center with bad eyesight and a Play-Doh body. And the damn goggles are fogging up on Schertz.

MaCabe Brown/Courier & Press/USA TODAY Network

That’s the only thing faulty about the 48-year-old coach’s vision. In 2021, he saw a vibrant opportunity at Indiana State, when others saw a long-dormant program. On the recruiting trail, he saw a big man who would flourish in his skill-centric style, when others saw a paunchy non-athlete. He saw a surrounding cast of fearless shooters and slashers, when others saw spare parts. He saw a place to run and gun and swish and splash, when others saw a dead-end job.

Now here he is in Year 3, Indiana State the champion of the Missouri Valley Conference for the first time since 2000. The Sycamores are an absolute blast to watch, putting the ball in the basket more efficiently than any team in the nation, with an effective field goal percentage of 59.8%. They have won 26 games so far, the most at the school since 1979, stirring up cherished memories of the only time this program was a national phenomenon.

No, Larry Bird is not walking through that door at Indiana State. But Robbie Avila did, and he’s got company. The Sycamores aren’t No. 1 the way they were 45 years ago, and they’re probably not going to the Final Four—they’re not even a lock to make the NCAA men’s tournament yet. But if you want a mid-major team to fall in love with as tournament basketball begins this week, there is room on this reconstructed old bandwagon.

Robbie Avila and his big brother had a habit of wrestling, and as is often the case when brothers tangle, things get broken. Chief among those things: Robbie’s glasses.

After breaking yet another pair of them during yet another tussle in eighth grade, Robbie’s mom was finished paying for new ones every few months. Her solution: Robbie would wear his Rec Spec goggles as everyday glasses for the foreseeable future. He’d already been wearing them in sports since starting as a football player in third grade (“I couldn’t really see anything on the field without them,” he says). After a parental decree, he would wear them to school and everywhere else.

That lasted for two years, an awkward thing at an awkward age. “They’re obviously not the flashiest thing,” Avila says.

He got used to it, and the goggles became something of a trademark for a rising standout at Oak Forest High School in Chicago’s south suburbs. Now the player and his goggles are celebrated in Terre Haute, where a fan sponsored a giveaway of 3,000 pairs for “Be Like Robbie Day” in January. There were T-shirts featuring goggles on a basketball that the entire team wore for warmups.

“That was amazing,” Avila says. “If someone can use me as a platform for kids who are a little insecure about wearing them on the court, it’s a blessing.”

Avila’s cult hero status, complete with multiple nicknames, is not something the world saw coming when he arrived as an unheralded freshman at Indiana State in 2022. High-major programs had no interest in a pudgy kid who couldn’t jump over a sidewalk crack, but Schertz was extremely excited about him. He worked hard to beat out Missouri Valley rival Northern Iowa Panthers for the big man.

“He thought the game like a point guard,” Schertz says. “He passed the ball like a point guard. And then when I got to know him, he has a maturity level you just don’t see.”

Schertz hadn’t even coached a game yet at Indiana State and was relying on tape from his time at Division II Lincoln Memorial to show Avila how he would fit in his offense. But the vision he sold was successful. The coach still has the FaceTime call from Avila in the call log on his phone from when he committed to the Sycamores.

“I knew the trajectory of our program had changed at that point,” Schertz says.

That quite literally has been the case: Indiana State was 11–20 in Schertz’s first season before Avila arrived. ISU went 23–13 last season with Avila starting 28 games as a freshman. Now, ISU is 26–5 and in the top 30 of the NCAA NET computer rankings with Avila as a developing star in a five-out offense that runs through his skilled hands.

He’s the Sycamores’ leading scorer at 17.6 points per game, No. 2 rebounder at 6.9 and No. 2 assist man at 3.9. He’s a perimeter shooting weapon, making 44 three-pointers at a 40% accuracy clip. He’s a pick-and-roll threat. He’s developed a back-down power game. He’s an offense initiator for a group of deadly shooters and daring drivers.

“He’s the fulcrum of the whole thing,” Schertz says. “We’ve got three guards, but they all play through him. That allows them to not step on each other’s toes—who’s really the point guard doesn’t matter, because he’s really the point guard. He handles the ball more than any of them and they play off him in those two-man games.

“And it doesn’t matter whether he scores 26 or he scores eight. He just plays. When your best player has that? Everybody else kind of falls in line. He’s that for us. You can build a program around him.”

The 240-pound Avila is certainly not quintessential, first-guy-off-the-bus material. He’s not the physical specimen who will intimidate opponents on looks alone. But once the ball goes up for the opening tip—which he is unlikely to win—things change.

“Avila’s a unique player in college,” Ball State Cardinals coach Michael Lewis says. “He can get a rebound and lead the break, you can play through him, he can step out and shoot threes. He has an unbelievable basketball IQ.”

Says Indiana State forward Jayson Kent, Avila’s teammate at Oak Forest and now again in Terre Haute: “That boy can go. I’ve played with Robbie since high school, and just seeing him develop from what he was in high school to what he is now—he’s the best big in the Valley, in my opinion. He can pass, he can shoot, he can dribble. Not a lot of bigs can do what he can do. It’s a blessing to play with him again and have these guys surround him to make everybody better. We all make each other better, and he’s the key to that.”

Kent is a key part of the lineup alchemy Schertz has created around his bespectacled center. The coach acknowledges that “we don’t call any plays for him,” but Kent intuitively finds the gaps and seams created by those who do have the ball in their hands more often. The 6’8″ Bradley transfer is also Indiana State’s primary dirty-work guy. He will sometimes be the only Sycamore battling for offensive rebounds and often is asked to guard every position.

“People might not think he’s our best player, you can make that case,” Schertz says. “But I think he’s our most important player.”

For proof of that, see Indiana State’s surprising two-game losing streak in February. Kent played just 17 minutes in the first loss, to the Illinois State Redbirds, after suffering a mid-game concussion. He missed the second defeat, against the Southern Illinois Salukis.

Kent was essentially told he had no role at Bradley, according to Schertz. Evansville-area product Isaiah Swope, ISU’s No. 2 scorer, was a Division II recruit at hometown University of Southern Indiana who arrived this season. Sixth man Xavier Bledson followed Schertz from Lincoln Memorial. Third-leading scorer Ryan Conwell is an Indianapolis product who transferred in after playing sparingly at South Florida his freshman year. Julian Larry is the lone major holdover from the longtime former Indiana State coach Greg Lansing’s program.

They’ve all linked arms here, in a fading mid-sized city on the banks of the Wabash River that divides Indiana and Illinois. It’s more than an hour to Indianapolis, and a lot farther than that to anywhere else of note.

Alex Martin/Journal and Courier/USA TODAY Network

Terre Haute—French for “high land,” as named by French-Canadian explorers and fur trappers in the early 1800s—has experienced many of the same economic peaks and valleys as the rest of the Midwest. Its population peaked at nearly 72,000 in the 1960 U.S. census, began to drop precipitously in the ’70s and was about 58,000 in the 2020 census. The irony-laced nickname they throw around here is “Terredise.”

Terre Haute’s place within Indiana’s celebrated basketball culture is similarly isolated. A city school has never won a high school boys state basketball championship and hasn’t even reached the title game since 1978. Hoosier native John Wooden began his head-coaching career at Indiana State, but stayed just two seasons before departing for UCLA.

There is, essentially, one high point. Since Bird took the Sycamores on the magical ride to the NCAA tournament title game against the Michigan State Spartans and Magic Johnson, there hasn’t been a lot to brag about here. Indiana State went without a winning record from 1981 to ’97 and since then has garnered a total of three NCAA bids. The last was in 2011.

Schertz looks around town, looks at himself, looks at his locker room and sees a lot of similarities.

“Terre Haute catches a lot of flack for different stuff, but you’re not going to find more loyal, blue-collar people,” he says. “We have a lot of guys in our locker room that are They Said You Can’t kind of guys. I was that kind of coach. … There’s been no yellow-brick road for us, but there’s been no yellow-brick road for the people of Terre Haute, either. We’ve all had to earn everything we’ve ever gotten. There’s a lot of overlap there—the community relates to us, but we relate to the community as well. We’ve not been gifted anything, we’ve had to earn it.”

The irony accompanying Schertz’s vision for Indiana State is this: He had no such clarity for himself as a young man. He was an accidental basketball player, a burned-out tennis prodigy with a chaotic home life, a broken kid at loose ends.

Pushed by a father with stars in his eyes, Schertz was a nationally ranked youth tennis player at age 12. Paul Schertz had Josh move from New York to south Florida to train for a tennis career that was destined—by gene pool and parental pressure—to end poorly. Schertz was 5’6″ at 12 years old and still 5’6″ several years later, when he walked away from a sport that had ceased being fun.

He also walked away from home. His mother, Kathi, was grappling with substance-abuse issues. He was estranged from his father. He dropped out of high school and stayed with friends here and there, drifting.

Schertz’s grandfather, Seymour, took him in and urged him to get his GED. He took on part-time jobs and enrolled at Palm Beach Community College. Along the way, he started playing in a couple of basketball leagues, the gateway to an unexpected life’s passion.

A community college coach from New Jersey was watching a friend’s grandson play in one of those leagues in 1994. Jack Martin of County College saw the 17-year-old Schertz—now a lofty 5’8″—tearing it up in that game and offered him a chance to try out for his team. Schertz made the team as a backup guard, then bounced through a couple of other programs in Florida and North Carolina. At Piedmont Bible College, the idea took hold: He wanted to be a basketball coach.

“My dad said, ‘This is ridiculous that you would do such a thing. It’s a horrible decision to coach,’” Shertz recalls. “But man, I loved it.”

Paul Schertz didn’t like the decision at the time, but supported it by helping Josh land a spot as a student staffer at Florida Atlantic. That began a 10-year assistant odyssey that ended with him becoming the head coach at Lincoln Memorial. The program was chronically unsuccessful, but that quickly changed.

The Railsplitters improved to 14–14 in Schertz’s first season, then elevated to D-II heavyweight status for the next dozen seasons. LMU made the D-II tournament nine times, reaching the Final Four twice and finishing as the national runner-up in 2016. The 2019–20 team, which went 32–1, might have won the title if COVID-19 hadn’t canceled the tournament.

But breaking out of the D-II ranks isn’t easy. That’s where the vision of what Indiana State could be went both ways.

The school saw an accomplished D-II coach as the right man for its rebuild, when others only had eyes for D-I candidates. Instead of hiring a high-major assistant or a retread, ISU got a guy who won a gaudy 83% of his games. They saw something in him that would translate to the Missouri Valley Conference.

Dale Young/USA TODAY Sports

The vision was lost in translation at first. Lansing was a longtime, respected coach with a winning overall record (181–164), and he’d been replaced by a nobody. When that nobody started his tenure with a 20-loss season, there was some blowback.

A #FireSchertz hashtag started making the rounds on social media. And Schertz remembers returning to campus after a season-ending loss in the Missouri Valley tournament to Illinois State and hearing some students heckling him from the Rhoads Hall dormitory.

“Hey Schertz!” one yelled. “Go back to D-III!”

“It was D-II!” Shertz yelled back.

Everything flipped last season, and now the love affair is in full bloom. A “Schertz For President” sign appeared in the near-sellout crowd for the Bradley game, which was a Missouri Valley classic—a 95-86 OT win rife with sublime shot-making and dripping with tension. Afterward, the coach took the on-court microphone to thank the fans for creating a deafening home court advantage.

Schertz has made his peace with most things and people in his life. He repaired his relationship with his mother before her death from cancer. He’s in regular contact with his father. He can even watch and enjoy tennis, staying up all hours in January to follow the Australian Open. Life is good in Terredise, where the 10,200-seat Hulman Center has rocked all season.

“The Holy Grail of coaching is relationships,” Schertz says later, looking out through those foggy goggles. “But right below that is the amount of joy you can bring to people through this job. To see how happy those fans were, to see that many people in Terre Haute come together and support something. To have a night like this, I told the team this is a great moment, you’ll remember this the rest of your lives. But I also think our best moments are ahead of us.”

That brings us to this week, and Arch Madness, the venerable Valley tournament. Indiana State is deserving of an at-large NCAA bid even if it doesn’t win the tourney, but nothing is assured. The Sycamores will take some pressure—and a target as the No. 1 seed—with them to St. Louis. If they make the Big Dance, they will present a daunting Cinderella challenge to some opponent.

However the season ends, an uncertain future looms. After years of being a largely ignored winner, Schertz’s name is now in circulation for other jobs at a higher level. He may stay. He may go. But Indiana State’s most exciting March since 1979 has brought an improbable vision into full focus.